How politicians killed Paris’s art-squat movement

- Text by Eloïse Stark

- Photography by Eloïse Stark

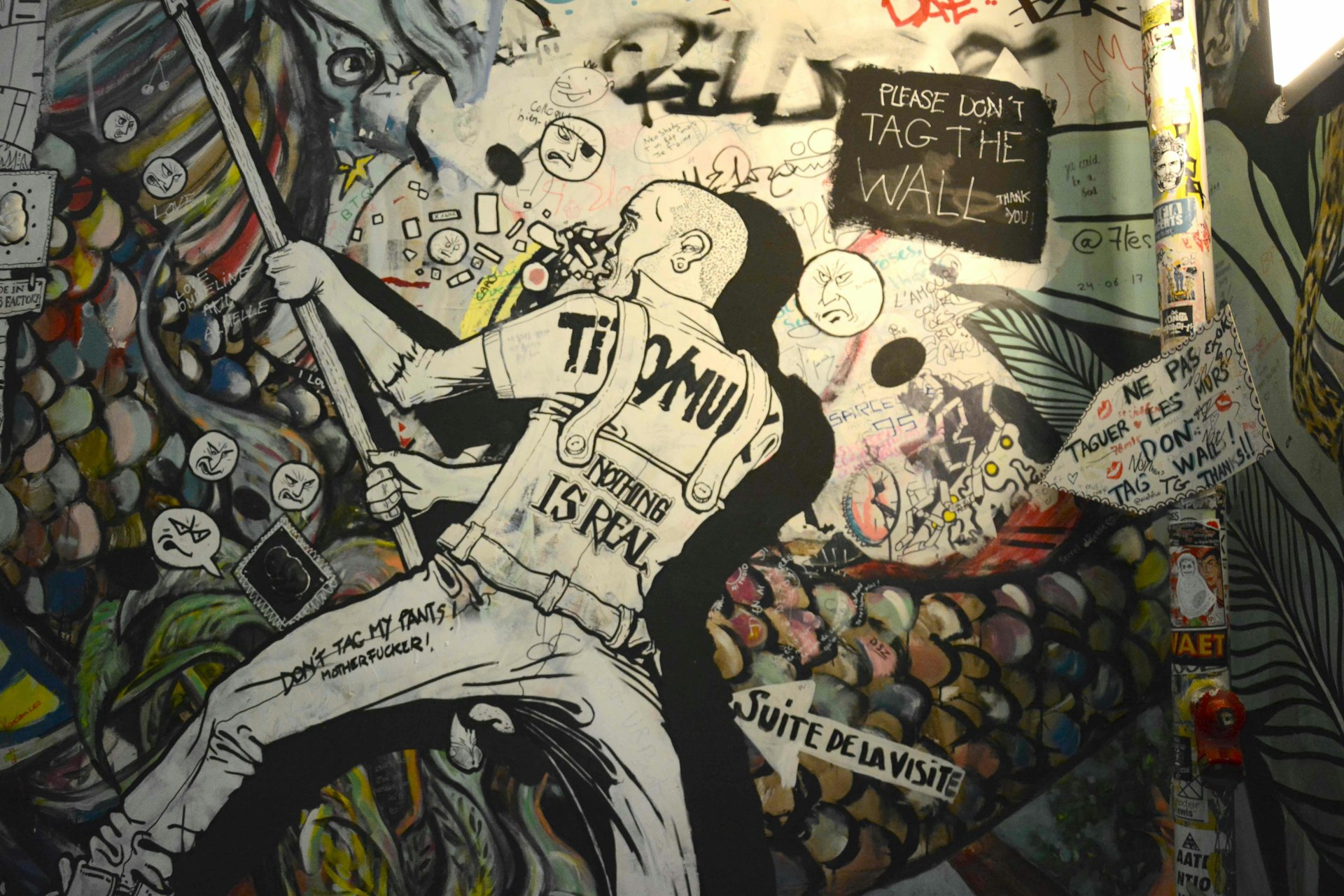

Artist Francesco uses his studio floor as a paint palette, and calls his ceiling the “Sistine Chapel.” While it may not be covered in religious frescos, it is packed with colourful, painted faces which stare down at you from every angle.

Francesco is one of 30 artists occupying number 59, Rue de Rivoli – a huge Hausmannian building in the very heart of Paris, on one of the city’s most upmarket shopping avenues. With paintings and sculptures dangling off its facade, the busy gallery stands out next to its neighbouring Swarovski, Mango and Gucci. It’s strange to think that the space – which now attracts 70,000 visitors every year – started as an illegal artists’ squat.

“When we first arrived, the house was filled with dead pigeons, it took us a month to clean up,” remembers Gaspard Delanoë, who founded the squat with two friends back in 1999. He’s sitting in his workspace-cum-gallery, which he baptised the “Igor Balut Museum” after the name of a stranger found at random in a telephone directory.

The gallery is really a collaborative work of art, where Gaspard’s own creations – oil paintings covered with brightly printed, provocative slogans – are mixed with metro tickets, dolls and random bric-a-brac.

“This place has the Guinness World Record for the Museum that has moved around the most,” Gaspard says. He set it up in every squat he ever lived in – eight in total. “I started squatting in 1994, and we got evicted every six months.” Each time, his artwork was destroyed, and he ended up on the street. “Getting evicted does get really tiring,” he admits. “Especially when you’re making love to your girlfriend and the riot police breaks down your door. It puts a bit of a downer on things.”

Luckily for Gaspard’s love life, things have settled down for him since the City Council legalised the squat in 2004. It’s a move that has become increasingly common in recent years: Paris now has over a dozen former squats which have been turned into legitimate cultural centres. The city realised it could capitalise on the cool factor provided by this counter-culture to help it compete with other European capitals – and attract educated young people to drive the creative economy, and accelerate gentrification.

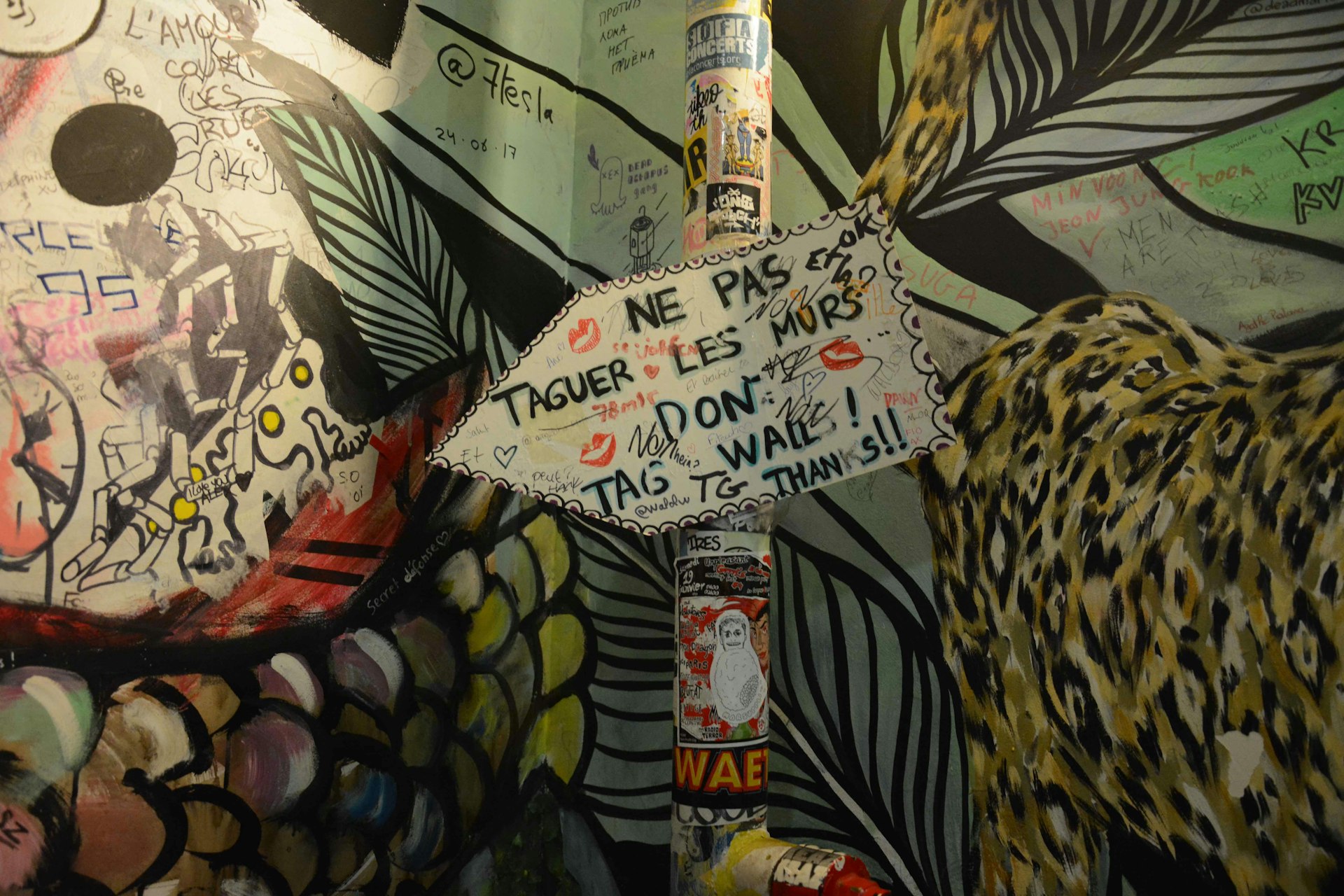

For the squatters, however, being legal comes at a cost. “When they legalised us, they banned us from living here, it became just a workspace,” Gaspard says. “We used to mix art and life. We didn’t want to separate them, because in today’s world everything is compartmentalised. Back then, we’d have orgies every week: we created together, we slept together. All that has disappeared.”

59 Rivoli is still home to beautiful, imaginative work, but it’s no longer a space for inventing new ways of living and loving. Nor is it the refuge for broke artists that it once was: the application process is competitive and takes several months, and residents have to pay – even if it is only 150 euros a month.

Going above board was a hard choice for the squatters, and some of them left in protest. They argued that signing a contract with the City Council went against the squats’ values of questioning property rights and reinventing community living. They say that this is exactly why Paris wants to legalise these spaces: to gain control over a space of dissidence.

“Over the past few years, we’ve seen a pattern,” says Emmanuel Ferrand, booker at La Générale, another now-legal squat which hosts musicians and artists in the 11th district of Paris. “The government has found a way to control these spaces, suffocating them not by direct repression but by reappropriating their codes. Legalising artists’ squats is like using them as a vaccine. It makes them harmless.”

It’s also a way of picking and choosing your squatters. “There are spaces which the town hall rents to artists because they don’t want them to be squatted by Roma people or undocumented immigrants,” Emmanuel explains. He says that Paris has effectively driven a wedge between “good squatters” (artists and creatives), and “bad squatters” (refugees and the homeless). While a few squats have been legalised, Macron’s government has increased pressure on the others. The “Elan Law”, enacted in November, makes evicting squatters easier than ever before.

Meanwhile, the squat ‘aesthetic’ is being milked for all it’s worth – not just by city hall, but also by private investors. To increase the value of an unoccupied property, the city council rents out bits of land awaiting construction work to events companies who create “ephemeral spaces.” Often, these become beer gardens which all follow the same recipe: furniture made of pallets, graffiti, exposed pipework and wiring… and an expensive bar.

The reappropriation of squat culture by companies sometimes goes even further. La Miroiterie was once a legendary musical squat in the working class Belleville area. They had raves and parties and a world-renowned program of upcoming punk rock artists. In 2014, they were forced to leave, and the site was sold to property developers. Construction work will soon start, and the squat will be turned into shops, an expensive spa, and a concert hall – but will still be called “La Miroiterie.”

Having both their place and their name taken was too much for the former booker Michel Ktu, who wrote an angry op-ed on the website StreetPress. “Taking our name like that is tomb raiding,” he wrote, bitterly. “The vultures are stealing everything we spent 15 years making.”

Yet, against all odds, new squats continue to be born. Gerard says he is part of a “network of staunch squatters,” and currently lives in a dilapidated building near Gare du Nord. It used to be the head office of a chain of jewellers, and there’s still a walk-in safe in the living room, amongst the sculptures, murals and mismatched furniture.

For years, the place has been home to up to 70 people at a time, attracting artists, musicians and actors. “In a squat, you have opportunities that you don’t have in a house to develop your creativity,” Gerard says, gesturing towards a huge paper-mâché wolf’s head hanging over the room.

A few months ago, he and his fellow squatters received an eviction notice, and soon they will be forced to move out. But for Gerard, the adventure isn’t over. The other day, he tells me, he spoke on the phone to the bailiff, who was organising for his housemates to be rehoused. The bailiff then asked if Gerard himself needed somewhere new to live.

“No, thanks,” Gerard replied, cheekily. “But we might meet again in my next squat.” He has already found the perfect abandoned building to occupy.

Follow Eloïse Stark on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.