In South Africa, sex workers are calling for justice

- Text by Daisy Schofield

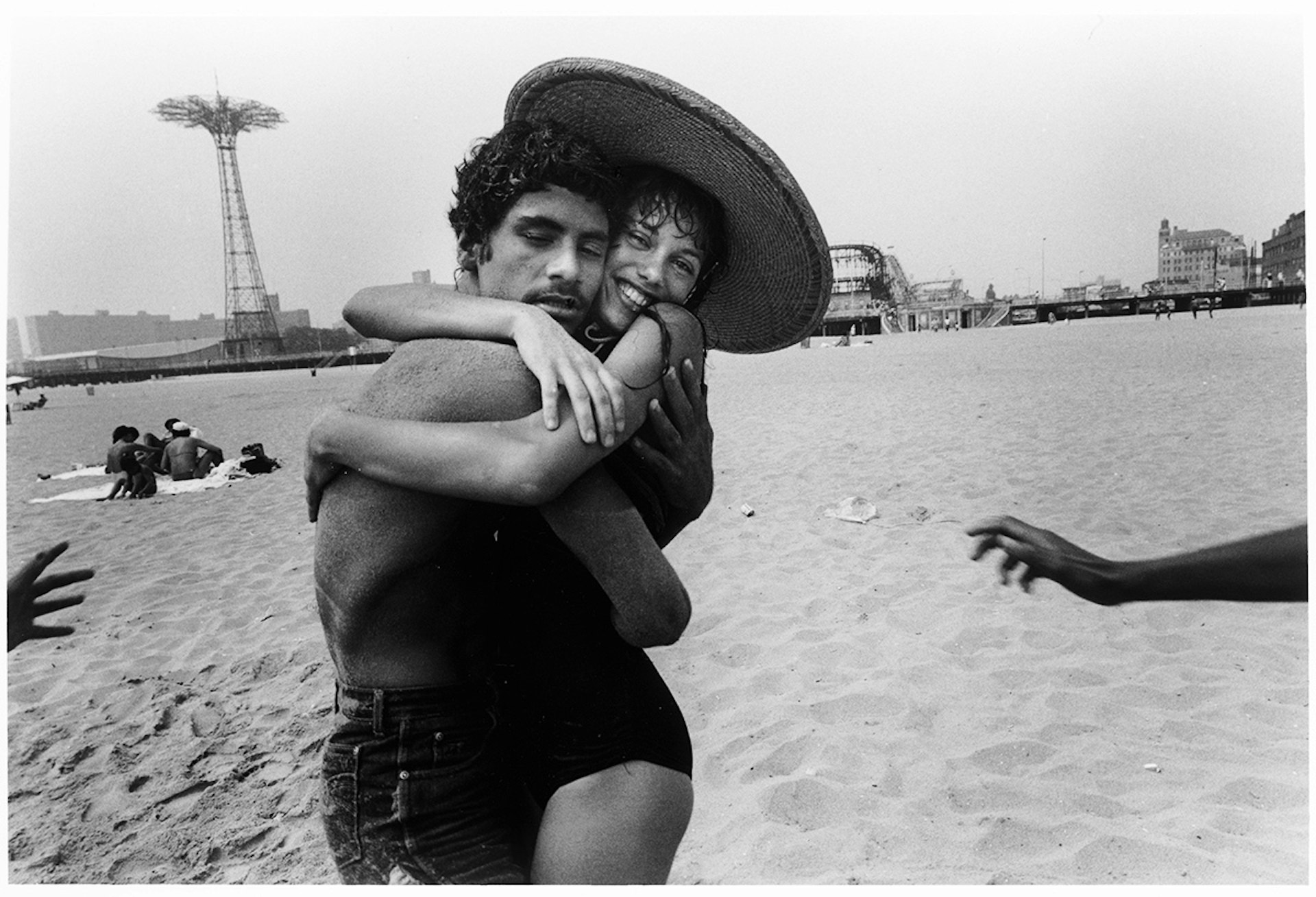

- Photography by SWEAT / Alexa Sedgwick

When reports emerged that Robyn Montsumi, a 39-year-old sex worker from Cape Town, had taken her own life in police custody this April, suspicions immediately started to bubble within the community.

“Robyn was a very happy-go-lucky person and a passionate LGBTQI activist,” says Gulam Peterson, a homeless, trans sex worker and friend of Montsumi. “She had a girlfriend; they were very much in love. It just doesn’t make sense.”

In a statement released at the time, SWEAT (Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Task Force) said the reports of suicide were “baffling”, and that people who saw Montsumi just before her arrest had described her as “upbeat”. “We just want to know what really happened,” says Peterson.

Activists demanding justice for Montsumi see her death as symptomatic of an increase in incidents of police brutality and gender-based violence in South Africa during the lockdown. Sex workers across the globe have been some of the hardest hit by the pandemic, and are currently facing serious consequences for their health and livelihoods. In South Africa, where prostitution is criminalised, these struggles are even more acute. Particularly in Cape Town, which has emerged as a hotspot for the virus.

Criminalisation has not deterred people from selling sex for a living in South Africa: it has, however, made it less safe. It undermines sex worker’s justice for crimes committed against them, such as the countless incidences of being laughed at by police when they try to report rapes, or being told that their profession means they cannot be raped.

It also makes them vulnerable to abuse from law enforcement. Police have been known to solicit money or sexual favours from sex workers in exchange for their freedom. “As soon as they know you’re a sex worker, they use their power to dehumanise you,” Peterson says. Sex workers are already forced to operate in dark and dangerous corners to avoid being caught by the police – but since the pandemic started, Peterson claims they have been “pushed even further underground.”

Because their profession is illegal, sex workers are unable to claim unemployment benefits at a time when their incomes have been drained. Megan Lessing, a spokesperson for SWEAT, says that no one quite anticipated just how severe the economic hit to sex workers would be because of the pandemic. “Sex workers in a criminalised area become very self-reliant and resilient because they have they have to be,” she explains. “And now, it’s been really tough because they are dependent on handouts for even the most basic needs – from food, to hygiene and sanitary pads.”

For homeless sex workers, the Cape Town government’s response has only exacerbated their plight. The establishment of Strandfontein camp – which was set up on the outskirts of the city by the government at the start of lockdown as an attempt to shelter homeless people – sent shock waves through the community. Without any social-distancing measures in place for the more than a thousand people sent there, and no PPE available, the camp was primed to become a hotbed for Covid-19.

Peterson was friends with many of the sex workers taken off the street and placed in the camps. “They were treated like they were nothing,” she says, claiming that people were beaten and pepper-sprayed, separated from vital support services like HIV medication, and made to sleep on the floor. There are also reports of sexual assault and deaths that took place at the camp. After public outcry, the camp was closed just over a month into its establishment, but the damage it caused is still being felt. “It’ll take months and months to deal with the fallout and the overwhelming human rights violations that took place there,” says Lessing.

The extent of the abuse against sex workers in the camp, and the gender-based violence that has taken place in South Africa during the lockdown, is yet to fully come to light. But often impeding justice for sex workers like Montsumi is that they are labelled ‘problematic’ victims, subject to moral shame, particularly in the face of criminalisation. Lessing hopes that the Black Lives Matter movement will bolster calls for decriminalisation – because, as she notes, many of the vulnerable sex workers are black – by recognising criminalisation as “state-sanctioned violence”.

With Cape Town only just reaching the peak of the virus now, Lessing predicts that many sex workers will have no choice but to start working again over the next couple of weeks. “When you’re desperate for an income, you tend to take a lot more risks,” she says. The harm caused by criminalisation is more pervasive than ever, but, galvanised by Montsumi’s tragic death, this is a community who will continue to loudly defend their human rights.

SWEAT has launched a campaign, titled #SayHerName, to have sex work in South Africa decriminalised. Find out how you can support by visiting the official website.

Follow Daisy Schofield on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.