The mundane real lives of Mexico’s star wrestlers

- Text by Seila Montes Gonzalez

- Photography by Seila Montes Gonzalez

As many others before me, my strange fascination with Lucha libre began once I moved to Mexico.

The first time I attended a match, I wasn’t sold. It just seemed like a bunch of big masked guys pretending to fight. But as soon as the lights went on, the mixture of the costumes, showmanship, acrobatics and atmosphere had me hooked.

The Mexican Lucha libre derives from Greco-Roman wrestling. It dates back to the mid-19th century, where it was born during the French invasion of Mexico. It’s a mixture of sport, athletics and theatrical sequences. As the wrestler Coco Rosa told me, Lucha actually benefits society. According to him, people come to the fights to vent their anger, so that when they go home they feel more relaxed. He also claims it helps them argue less with their family.

As a documentary photographer, it was clear from the moment I met the wrestlers that I wanted to get behind their masks. I wanted to hear their personal stories.

I learned that a lot of fighters had retired from wrestling because of old age or injuries. Others would work late in their day jobs because in Lucha there’s no retirement or medical insurance from the government nor the wrestling federation. Worshipped while in the ring, they worked mundane jobs outside the ring.

An average wrestler wins around 500 pesos per fight, which is around 23 dollars. A wrestler that appears on television can get from 3,000 to 1,000 pesos, which is around 150-800 dollars per fight.

The lucky ones have other careers that they can continue with after retiring. Others can train other fighters if their age and injuries allow them to. The less fortunate ones, though, work or sell whatever they can to survive.

Wrestlers are not exactly known for having university degrees or high-qualified jobs. Most of them come from humble homes and, in many cases, they start fighting at an early age to support their families. However, as I met more fighters I started to see many different kinds of people – even university graduates, like Ray Mendoza, who has a degree in dentistry and gives consultations for dentistry and acupuncture. Another was Fray Tormenta, a former heroin addict who decided to study at the seminary and became a priest. He founded an orphanage that he supported with the money he made from wrestling. The movie, Nacho Libre with Jack Black, is based on his life.

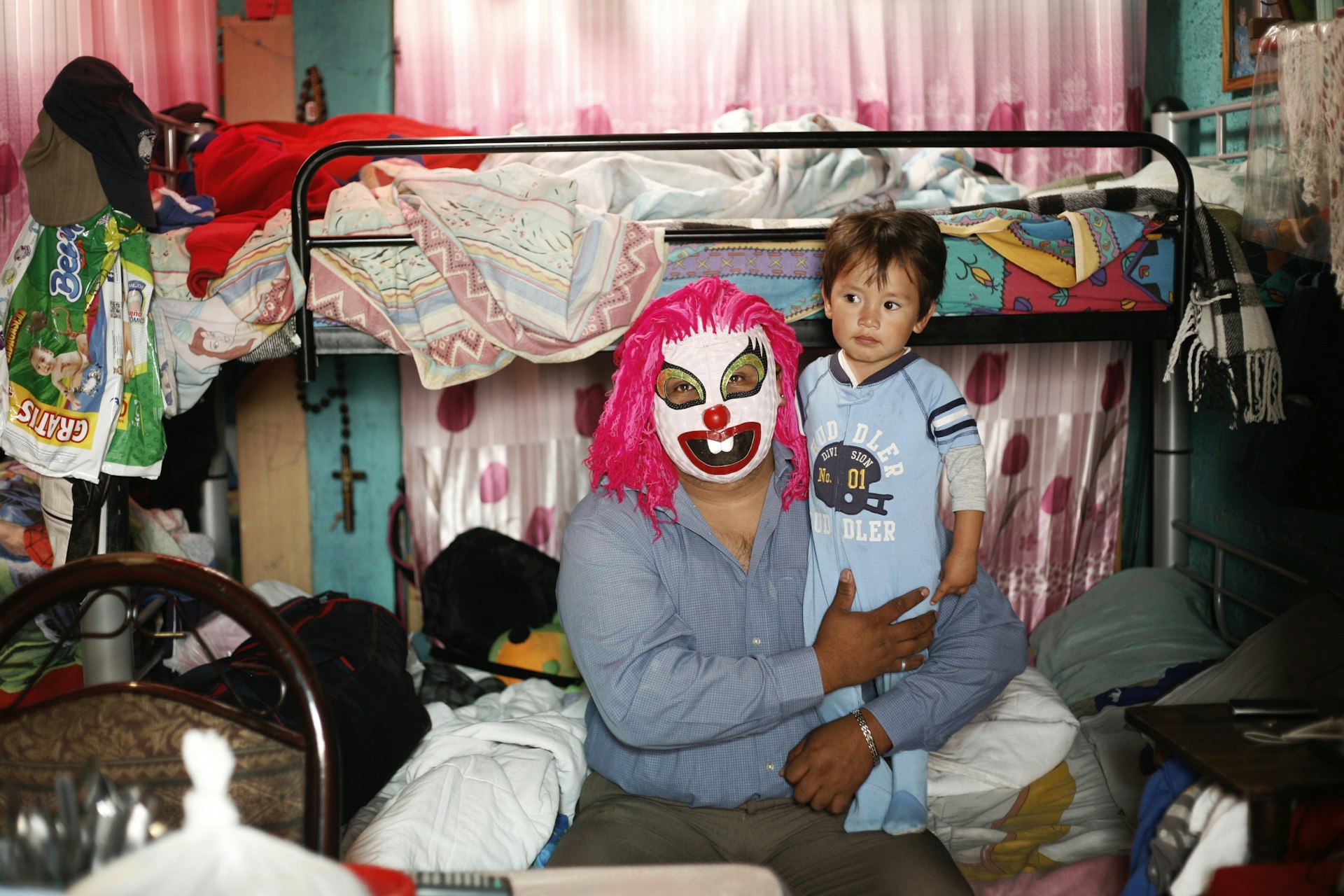

After getting to know all these personal stories, I wanted to take portraits of them outside of Lucha – in their houses, in their day-to-day lives, in the mundane jobs they do to earn their keep.

The only common denominator between them all was the masks and the suits, and the transformation as soon as they got into their characters. Their attitudes, poses and stances totally changed, revealing the actor, wrestler or comedian that they carried inside. As soon as they got into costume it came automatically. I could see the sudden change in confidence.

The only common denominator between them all was the masks and the suits, and the transformation as soon as they got into their characters. Their attitudes, poses and stances totally changed, revealing the actor, wrestler or comedian that they carried inside. As soon as they got into costume it came automatically. I could see the sudden change in confidence.

These characters and their masks are part of the Mexican popular culture. They receive praise and adoration while they are in the ring, but then they get neglected by the government as soon as they’re out of it. It’s as if, once they are forced to retire because of age or injuries brought on by the career, they get forgotten.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.