The rights of UK sex workers are under threat – why?

- Text by Lydia Morrish

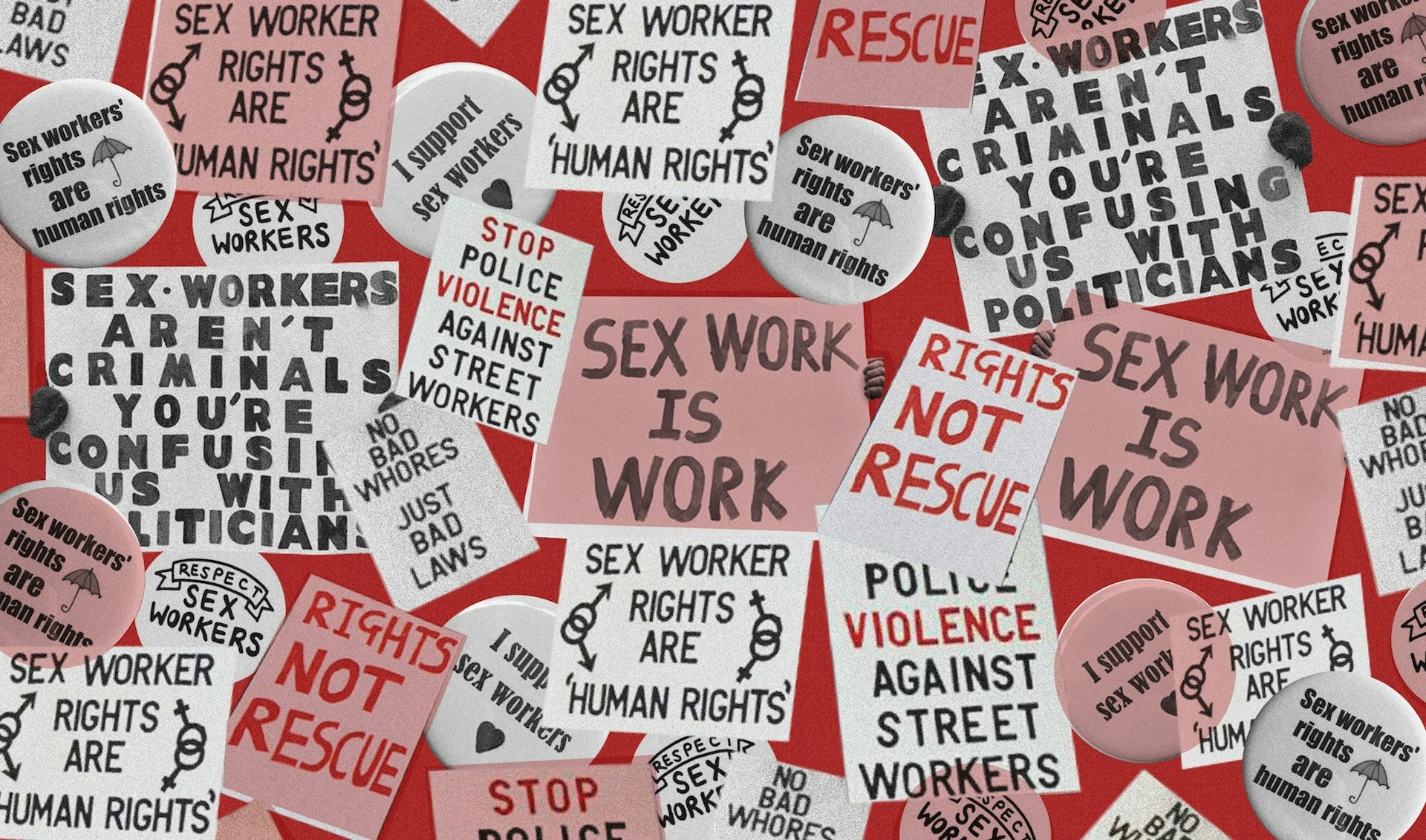

- Photography by Juno Mac

- Illustrations by Sophie Mo

Lucy* loves being a sex worker. The 21-year-old Londoner is independent, chooses her own hours and sets which days she works.

Like many sex workers in the UK, Lucy uses AdultWork, a popular adult website where escorts can advertise their services. Most crucially, it also allows them to screen potential clients by leaving reviews and warning each other of dodgy, or dangerous, buyers. Some clients even send Lucy selfies that she can reverse image search to check they’re genuine before setting up a meeting.

“It reassures that your meeting is safe,” says Lucy during a visit to a buzzing women’s centre on a quiet side street in North London, where the English Collective of Prostitutes, a self-help group of sex workers, is based.

Unfortunately, the protective digital barrier of websites like AdultWork could soon be taken away, and sex workers across the UK may be driven offline and underground. British politicians are looking to push through legislation that would ban the advertising of sex work online and criminalise the buying of sex – a move which would effectively turn the sex industry upside down.

But a growing resistance movement of sex worker collectives, organisers and allies across Britain is trying to stop the march towards criminalisation in its tracks.

“We’re trying to make sure sex workers really have a seat at the table,” says Blair Buchanan, a 27-year-old sex worker and activist. She works with Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement (SWARM), as well as Decrim Now, a coalition of sex workers pushing for decriminalisation. Buchanan is fresh from a meeting with an organisation she is lobbying to support the coalition’s aims. One of her main activist gigs is to persuade political groups and organisations to support sex workers’ rights before limiting laws are introduced. “I feel like we’re getting somewhere.”

Currently in England, Wales and Scotland, the act of prostitution is legal, but everything around it – soliciting in a public place, managing a brothel, pimping and kerb-crawling – is outlawed. Buying sex could soon be illegal too. The All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Prostitution and Sex Work, a cross-party group of politicians brought together to investigate sex exploitation in the UK, recently condemned adult sites like AdultWork and Vivastreet, saying such outlets were a “significant enabler of sexual exploitation in the UK.”

If the APPG gets its way, all online sites where sex workers advertise in the UK will be banned. Even sex worker support sites like SAAFE (Support and Advice for Escorts) could be affected.

e

Such a move would follow in the footsteps of the United States’ FOSTA/SESTA bills passed into law in April that ban websites from hosting ads for sexual services. While supporters of the package said it would help end online sex trafficking, the law has proved to be damaging for those consensually in the industry. They say it has driven them offline and into riskier situations, and painted an image of sex workers as victims of sex trafficking by conflating consensual sex work with non-consensual sex work. The bills fail to differentiate between the two.

“The impact of FOSTA/SESTA has already been felt around the world,” Juno Mac and Molly Smith, sex workers and co-authors of Revolting Prostitutes, a timely new book on sex worker rights, tell me. “Many sex workers in the US relied heavily on Backpage and Craigslist for work, and the loss of these platforms was felt like any worker suddenly made redundant with no severance.”

If Britain introduces similar laws, the impact on the UK’s estimated 73,000 sex workers would be significant.

“I’d have to work on the street or with someone else who might possibly exploit me,” says Lucy. “I wouldn’t have a chance to screen my clients like I do online.”

Instead of protecting sex workers, such laws can, in fact, be a catalyst for exploitation. As an example, Mac and Smith point to the “influx” of managers (pimps) who have offered sex workers assistance in the wake of the law’s introduction in the US. “FOSTA/SESTA removes a tool that allowed sex workers a degree of independence, and is therefore in some respects a gift to those who want to profit from the sex work of others.”

But Britain’s sex worker collectives refute the mainstream belief that the sex industry is dominated only by those who are being exploited. Many of the activist groups I meet point to the largest ever study into migrants working in the London sex industry in 2011. It found that only six per cent of sex workers had been trafficked.

“I definitely chose to do sex work,” says Lucy. “I could exit the industry if I wanted to.”

Of course, the situation is different for all sex workers. Buchanan, a former drug user, says the industry is not without flaws: assault, exploitation, evictions and deportations are common. Many sex workers actively campaign against the industry as a whole because of that. “I worked in exploitative conditions and I recognise that,” she says. “We’re not trying to pretend those things aren’t happening, but what we are trying to say is the laws are exacerbating harms.”

MPs have suggested adopting the “Nordic model” to address sex trafficking concerns. Popularised by Sweden, it criminalises punters but keeps the selling of sex legal in a bid to flatten the industry. But there have been knock-on negative effects in the countries where the model is active. Since it was introduced in France in April 2016, sex workers there face increased violence and poverty, while violence against sex workers in Ireland has more than doubled since the model was introduced in 2017. According to UglyMugs.ie, an organisation that supports sex workers in the Irish Republic, sex workers reported 54 per cent more crime in the year since the change.

Instead of protecting sex workers, the Nordic model leads to a pool of clients that are more comfortable with breaking the law, says Blair. It also results in police using women as “bait” to find men looking to buy sex, she says. “It makes the sex worker’s body the scene of a crime.”

Lucy says that a similar model in Britain would make her less able to turn to the police for help. “I’d have fewer customers and might end up giving a service I wouldn’t usually do, or seeing someone I don’t feel 100 per cent safe around,” she says. “I’d end up taking more risks.”

Ultimately, sex worker collectives across Britain and beyond want to be treated as legitimate workers. To do that, they say the public perception of sex workers as an underclass needs to change. “We’re just normal people and we’re happy doing our job,” says Lucy.

“It is a fact that sex work puts food on the table, pays the bills and provides the material resources that thousands of families need across the UK,” says Buchanan. “Whether or not people like that work or feel that it’s moral or valuable, it is obviously work.”

Many modern feminists oppose sex work on the grounds it makes women sexual objects and playthings to be commodified. But opposing sex work on ideological grounds overlooks the real-life situations of many low-income, working-class women and people of colour. “Contemporary feminists’ disapproval of prostitution remains unmoored from pragmatism,” say Mac and Smith in their book. “More political energy goes to obstructing sex work than to what is really needed, such as helping sex workers avoid prosecution, or ensuring viable alternative livelihoods that are more than respectable drudgery.”

Trying to make it illegal, Buchanan says, obfuscates the real reason many women go into sex work: poverty. “There’s a reason most sex workers are poor women, undocumented migrants, people of colour and LGBT people.”

Buchanan is urging several LGBTQ, migrant rights and leftist organisations to support full decriminalisation of the sex industry ahead of a Home Office-funded report by Bristol University, which is set to be published in Spring 2019.

“It is a slow, laborious process,” says Buchanan, “but it has been incredibly fruitful and we feel like we’re getting somewhere to make it clear that this isn’t just a niche issue. It is something that affects us all in society.”

*Names have been changed for privacy reasons.

Follow Lydia Morrish on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.