The migrants left abandoned after a Marseille building fire

- Text by Frank L’Opez

- Photography by Gerard Bottino via Twitter

“We don’t have rights, we don’t exist, we are not protected,” says Adafe Clement Romeo, a resident of a Marseille housing estate that suffered from a deadly blaze last weekend (17 July). “And you know what broke all the Nigerians hearts, what broke our hearts? After the incident, we were watching on News 24. The three people who died were addressed as non-documented migrants. Even when we die, we are seen as nothing.”

Romeo’s voice cracks as we talk outside Dar Lamifa, a small music venue in Noailles, a mostly African populated neighbourhood in the city centre. It has been provided by a local organisation to use as a temporary kitchen. Here, Nigerian women prepare food every evening for the families who survived the fire that swept through the Les Flamants housing block in the isolated northern neighbourhoods of Marseille.

Romeo is 23 years old with wide eyes. His baseline energy is wired to the point of short-circuiting as he recounts the details leading up to the tragic incident which caused the death of at least three Nigerian nationals, and has left hundreds of people homeless and others hospitalised, among them a small baby.

Drame aux #Flamants. Ce document montre les marins-pompiers lançant la grande échelle à leur arrivée à 5h30 ce matin pour sauver les occupants dont trois se sont déjà défenestrés#Marseille pic.twitter.com/0a0Vt0MDiu

— David Coquille (@DavidLaMars) July 17, 2021

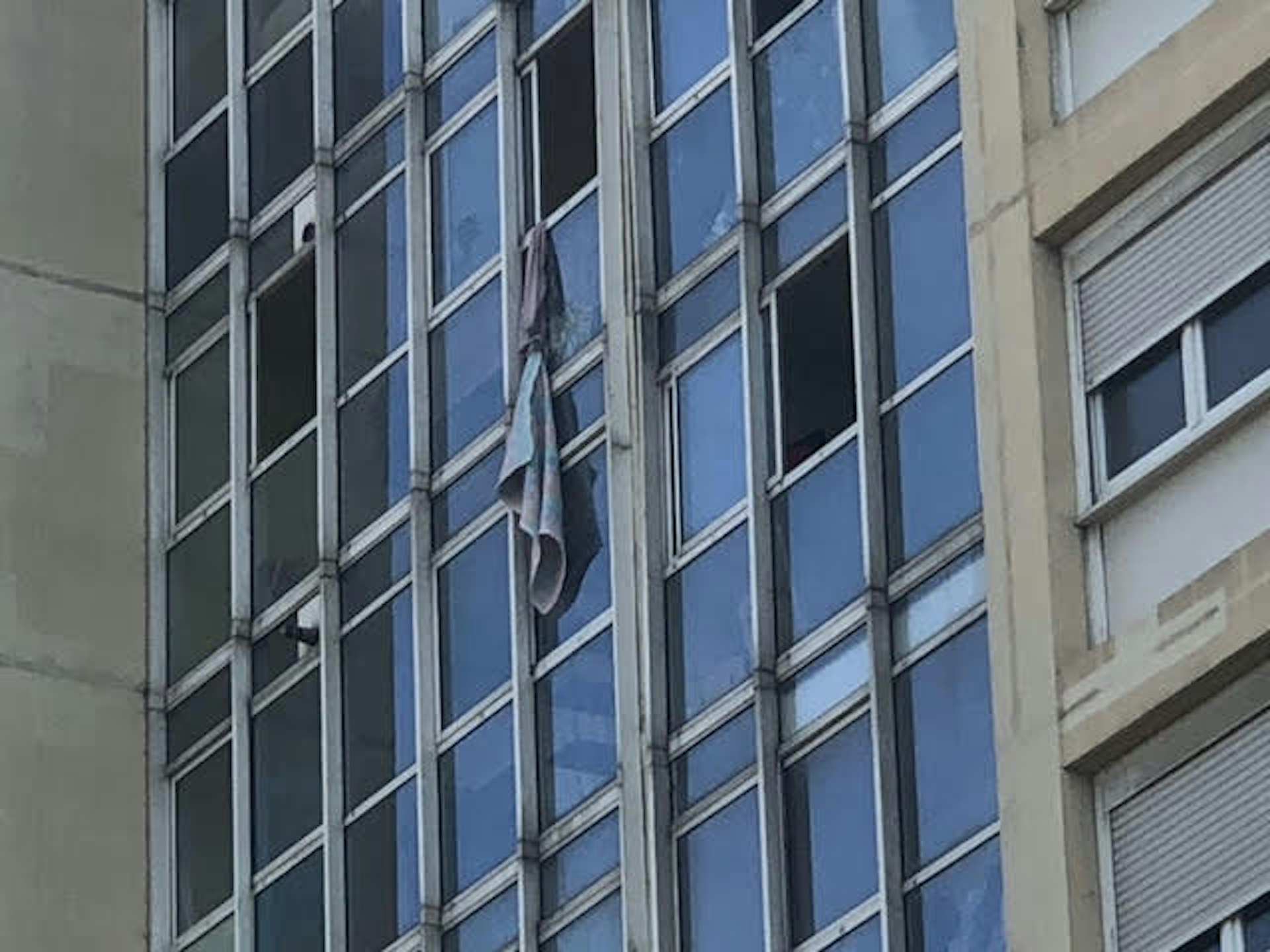

In the early hours of last Saturday, hostilities between Nigerian families and drug dealers came to a head. A criminal inquiry by the police is underway to investigate how the fire started on the 2nd and 10th floor of the building. Some residents desperately tied sheets together to climb down from their floors; others threw themselves from their windows to their death.

The Les Flamants high rise is typical of social housing that lies in neglect in the poorest neighbourhoods of Marseille. Drug dealers reportedly ran these blocks, charging a fee to open the boarded-up flats and then enforcing low monthly rents.

“Every day, people were getting beaten by the gangs. We had enough of making illegal payments and being oppressed,” Romeo tells Huck. “If you wanted to enter your apartment, you had to stand in the same line as those who came to buy drugs. We have young children but we have no choice, the government doesn’t care.” Despite Les Flamants residents making countless statements to local police that they were in fear of their lives, very little was done to protect them.

Alieu Armani is a member of the Association of Pada Users – an organisation of 500 members from 25 different nationalities set up to fight for the rights of asylum seekers in Marseille. He is originally from Sierra Leone, and has had close contact with the families for two years. “If people are neglected and not housed, they have no choice but to squat. It is a critical situation,” he tells Huck. “They need shelter, health care and even food. This is what it is to survive alone. The process of asylum can take years and in this time, these families are vulnerable. Local government tell us that housing is not provided for all asylum seekers because they don’t have the facilities, not for anyone, not even French citizens.”

Knotted bed sheets hanging from the facade of Les Flamants from which residents attempted to escape

Headlines in the French press referring to ‘SQUATTERS AND DEALERS’ in newspapers such as Libération give the sense of a story being buried in the mire. It is, after all, far easier to distract from society’s collective responsibility when humanity is swapped out for sensationalism; when the focus of the story lies in the shadow of criminality. “If people feel safe and have the authority to work they can look after themselves,” says Armani. “These people were not in gangs, they only come here because they have problems in their own countries. They need a safe place to live and they come to find structure… to make something of themselves.”

Back in the Dar Lamifa venue, I talk with Gregory from Aouf, one of many charity organisations in Marseille doing what they can to help as the survivors await further action from the local authorities. “It is a social emergency, even though most of the families have been temporarily rehoused for now,” he says.

“Some are in hotels but others are back on the street. What they need is a means to prepare food. They have no kitchen or even a fridge where they have been placed and here they will cook around 200 meals a day.”

A few of the women from Les Flamants are in the kitchen in the back chopping up chilli peppers for jollof rice and pounding out yam. I ask them how they are feeling. There is a sense of shock that permeates through their hardened expression. But, the sense of purpose and collectivity that buzzes in the kitchen is moving. Amid the shouting and belting laughter, Adam, a young woman with short hair and fierce confidence, seems to be the focal point of all activity. We step into the main room where three very young boys sit at a piano banging out discordant notes with their fists.

“I was there for around one year, paying rent every month with my family,” Adam says. “If you don’t get them the money, there is no question, the dealers just beat you. Once we started calling the police it became very dangerous for us, but the police don’t care about refugees or abandoned houses. The dealers put the fires in the stairs to trap us. People were hanging from the side of the building. I saw a woman who risked coming down the stairs with her whole body on fire.”

“You want to see?” she says, holding out her smartphone and pressing play on a video. It reveals the close-up of two bloodless young men in their underwear. They lie crumpled together on tarmac as howls of anguish overwhelm the tinny speakers. Their arms and legs broken beneath them; blank eyes open, they are lifeless and gone. There is blood, bones and a broken smartphone. One jumped with a small bag of belongings that is still tied around him. It is a horrifying watch.

The authorities have made plans to simply destroy the block but the survivors are yet to hear of their own fate. From one diabolical situation to another, they have no choice but to wait again; right now in this room carrying the emotional weight as mothers, wives and girlfriends. This is more than a case of people not having a place in society or being refused asylum. These are young families with nothing left but hope, a hope that they clutch at for their children.

As the interior minister Gérald Darmanin tweeted his condolences to the families concerned, an open letter to the Mayor of Marseille and the authorities beyond was written by the AUP. It asks if there are any plans to offer permanent accommodation that would be considered to be appropriate shelter, drawing attention to the lack of psychological support, the scarcity of food in emergency accommodation, and above all, the lack of help for the families of the victims who have not been given access to see the bodies. The letter is signed off very simply: “This lack of support does not seem worthy of France.”

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.