The radical history of Black-led self-building in Lewisham

- Text by Jade Chao

- Photography by Still from Nubia Way (Copyright © Architecture foundation, 2022)

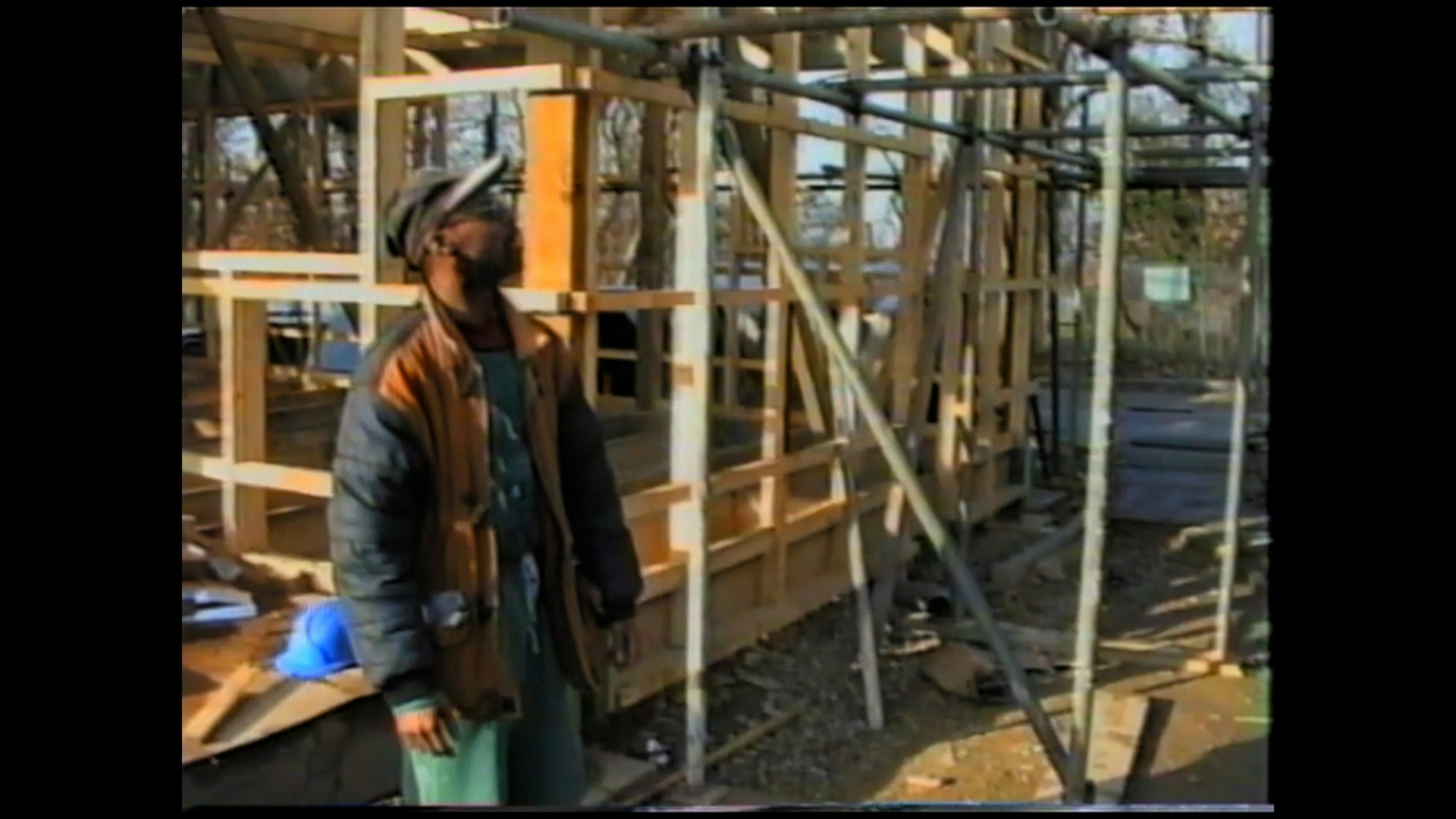

It’s 1996, and Leonard Guy and his soon-to-be-neighbour Errol Hall are keeping watch over their partly-built homes from a caravan on a construction site in Lewisham. Guy’s camera records a timber skeleton of a house. A light dangling inside illuminates the wooden frame. “My yard in the night-time,” Guy announces proudly. A space heater jangles metallically as the two young men speak to the camera.

“It’s nice [working as security] as a pair, actually,” says Hall. Guy agrees. He swivels his camera to point up at his face, in spectacles under a slanted baseball cap. “You don’t have to be on your own thinking C18 [Combat 18] or National Front’s gunna come and burn the place down.” (He is referring to the far-right groups that have subjected ethnic minorities in the UK to terror with high-profile demonstrations and attacks).

Guy is one of several members of a Black housing co-operative who share their experiences of building their own homes in Southeast London in a recently released documentary from the Architecture Foundation. The film combines present day interviews with Guy’s homemade footage, retelling the project’s story. Fusions Jameen – the collective behind the Black-led, self-build co-op – formed in response to the long council housing waiting lists for Black people. In 1994, they were seeking Black people to build their own homes on a thin piece of land in Downham, Lewisham, that became known as ‘Nubia Way’. Fusions Jameen recruited its builders through word of mouth and adverts in publications, specifically directing Afro-Caribbean people to apply – particularly people in need of housing.

Completed between 1994 to 1997, Nubia Way is the second of three Black-led self-builds made by the group in Lewisham during the ’90s. The first, Fusions 1, was an early adopter of the housing association Chisel’s ‘Self Build For Rent’ model, which gave self-builders reduced rent in exchange for their time and labour. Built across a split site in Brockley Park and Lowther Hill, with the assistance of architect Martin Hughes, it used modular timber frames, which eliminated the need for specialist trades like plastering or bricklaying so that ordinary people could build their own houses and adapt them to suit their needs. At 13 houses, Nubia Way is the largest ethnic-minority-led self-building project in Europe.

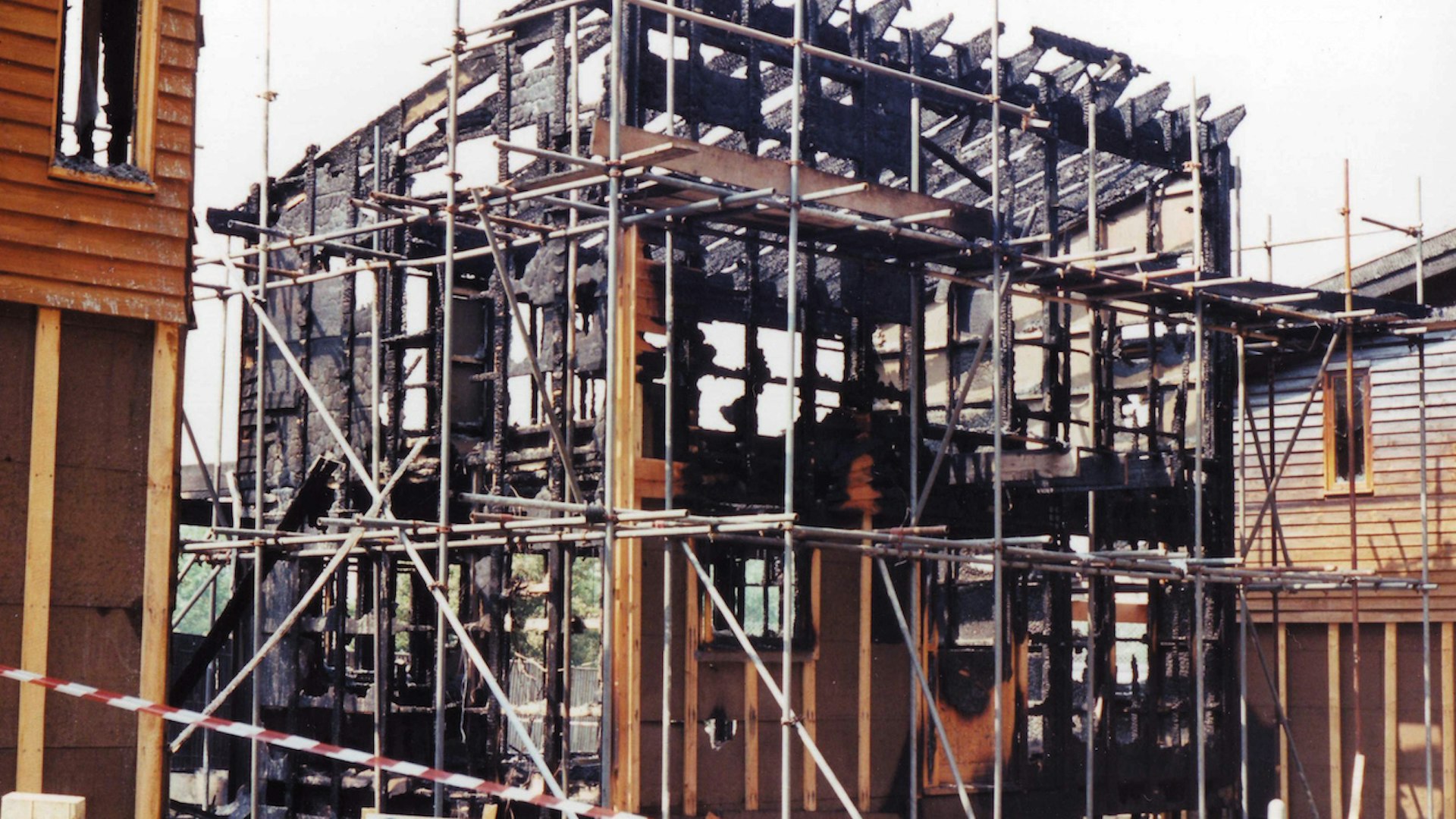

As the scene of Guy and Hall keeping watch of their homes shows, the threat of racist attacks was ever-present. Far-right groups committed three arson attacks over the course of the build, the worst of these destroyed a house on the build and severely damaged two others.

A new parent in 1994, Hall was looking for a house with enough space so that his son could live with him. He felt his odds were slim, noticing that single mothers were more favourable candidates for council housing compared to single fathers like himself. The project offered Hall a unique opportunity: “It was a two bedroom house, garden, modern, ecological, energy efficient,” he says. “I was a socialist. I thought, what a good thing to do. Get together with a bunch of people, help each other, build social housing. And then when I don’t need it anymore, someone else can move in.”

The process of building consisted of moments of exhilaration, as well as mundanity. Hall recalls erecting the timber frames, which he says was his favourite part: “There are bits of wood that you’ve cut with your own hands, you’ve been sorting them and drilling holes in them and measuring them. All of a sudden, you lift it and bang, there’s your house.” There were long days: “My least favourite… it was probably when we were working in the rain and we had those yellow plastic suits you put on, so we looked like fishermen. The mud was so bad that you couldn’t get your foot out the ground, and someone would have to come and dig you out with a spade.”

Documentary is vital as a medium for exploring radical histories such as Nubia Way’s. Reflecting on the film project, director Timi Akindele-Ajani says the affordability of some video equipment, and nimbler teams, democratises the process of storytelling. “It is important for film to be taken out of the hands of the powers that be and made on a smaller scale,” says Akindele-Ajani. “These histories, which may be more niche, can still get their time.”

They can also be told with more depth and care, and from different perspectives. A number of the team working on this project entered filmmaking through specialist fields. They include producer Rochelle Malcolm, a PhD student of 20th Century Black British arts and activism, and her fellow producer and co-producer Rosine Gibbs-Stevenson and James Thormod, who were trained in architecture. The film has toured architecture festivals and local community events in London.

At one such event, for students at the London School of Architecture, Thormod explains how his interest in Nubia Way began: “I came into it from the point of frustration. Frustration that this story wasn’t like told or part of a self-build narrative,” he says, “Unfortunately Black stories do not receive the same kind of limelight.” Akindele-Ajani agrees, saying: “The saddest thing about this is it’s just one piece of Black history that we don’t know. There’s hundreds of others.”

25 years on from Nubia Way’s completion, today’s crises of housing warrant more schemes like it. Homelessness for BAME people has risen 18 per cent in the last two decades and the government found that BAME households are more likely to be overcrowded. But prospects can feel bleak for those interested in self-build from a community-led perspective. Housing associations including Chisel, which control social housing in the UK, are businesses that operate more commercially than they did when they were created in the 1980s. Still, there are some reasons to be hopeful. Gibbs-Stevenson points to the ‘help-to-build’ scheme established by the government earlier this year, while Hall has been researching low-cost building methods for a new project he’s devising.

Hall reminds self-builders to be clear on the end goals of their battles. Their group was negotiating the interests of the media, the housing association, and architects – all while being vulnerable to violent right-wing attacks.“But all the time you are carrying the risk,” he says, “You are doing the work and it’s your home at the end of the day that you’re trying to secure.”

Despite all this, the thirteen finished houses are all still standing, along with their close-knit community of residents. “I think what we did was unusual and ambitious and good, and we achieved it,” Hall says. In the present day’s bureaucracies in planning policy, and the domination of large companies who lead building development in the UK, Nubia Way’s achievement also lies in its ability to still resonate in this generation.

At his talk for the architecture students, fellow Nubia Way builder Andre Howard posed a question to the audience. How many of them would be interested in building their own home? There’s a laugh across the room, because all of them are nodding.

Watch Nubia Way: a story of black-led self-building in Lewisham here.