Hackney’s Pho Mile and its history of resistance

- Text by Georgina Quanch

- Photography by Theo McInnes

In Vietnam, we don’t ask, ‘How are you?’. Instead, we greet each other with, ‘Ăn cơm chưa?’ (‘Have you had rice yet?’). Food seeps so deeply into our cultural veins that it’s the first thing on our minds whenever we meet family or passersby on the street. The Vietnamese community cares about when they last ate a meal, because we know what it means to have gone without. Telescoped into those three words are both our tender respect for food, and a communist country’s long history of war, strife and hunger.

It’s why my grandma shudders at the thought of locusts, which during her childhood sounded a death knell for her village because it meant a poor rice harvest. It’s also why, after she spends hours making soybean milk from scratch, she always syphons off the top part (the creamiest part) for me and my brother. In that gesture, the vast linguistic and generational gap between us falls away.

Food as an expression of love and family is one reason why Phở mile in east London created a sense of home for the Vietnamese community in Britain. When the first refugees from Vietnam and its surrounding countries resettled in Britain 40 years ago, they were proactive in trying to make a living through any means they had says Pierre Palluet, manager of Centre 151 – a Hackney-based community hub founded in 1985 to support refugees from Vietnam, Lao and Cambodia. “Many of them clustered in east London – they looked around and just made things happen. Phở mile came into being by accident,” says Pierre.

Chi Hien Ly, owner of Viet Hoa, was one of those trailblazers. In 1992, she and her husband set up a makeshift canteen in the Old Bath House in Hackney. The building belonged to the An Viet Foundation, a community centre for Vietnamese refugees. The couple had no experience with running an eatery, and used money gifted to them at their wedding to kickstart the business. In the first few months, they slept on cardboard boxes on the canteen floor. “We had to ask our customers if we could use their shower. We got scared at night of intruders, and had heard ghost stories, so we slept with a knife by our side!”

“When you’re young, and you’ve lots of energy, you say ‘Whatever!’ – we just had to believe,” Chi Hien adds, her face lighting up. They started with two popular noodle soups: Phở, Vietnam’s national dish, and the spicier Bún Bò Huế, flavoured with beef, fermented shrimp paste and pig blood. While authentic ingredients were expensive and hard to come by back then, it didn’t matter. “For the first time, our community had somewhere to eat our own food, speak our own language and meet other Vietnamese people,” she recalls.

Chi Hien, who now lives with her children in Essex, sought refuge in England in 1982 when she was 13 years old. English school was hard for her and she was bullied a lot. After she finished university here, she moved to America for a few months, just to visit. During her stay in America, which accepted many more Vietnamese refugees than the UK, she witnessed her community thriving.

Chi Hien was desperate to recreate the chatter and family feel of LA’s ‘Little Saigon’ – a beehive of Vietnamese-owned businesses – back in Britain. Introducing English palettes to Vietnamese cuisine took some guiling. “English people didn’t yet know about our food, so initially we put on the menu sweet and sour chicken and chicken chow mein – things that they knew. Once we got them into the restaurant, we slowly introduced them to Phở and Bún Bò Huế,” says Chi Hien. After she opened up a new site, Viet Hoa, which translates as ‘blossoming’, other budding Vietnamese restaurateurs followed her lead. Suddenly the UK’s own Little Saigon was born.

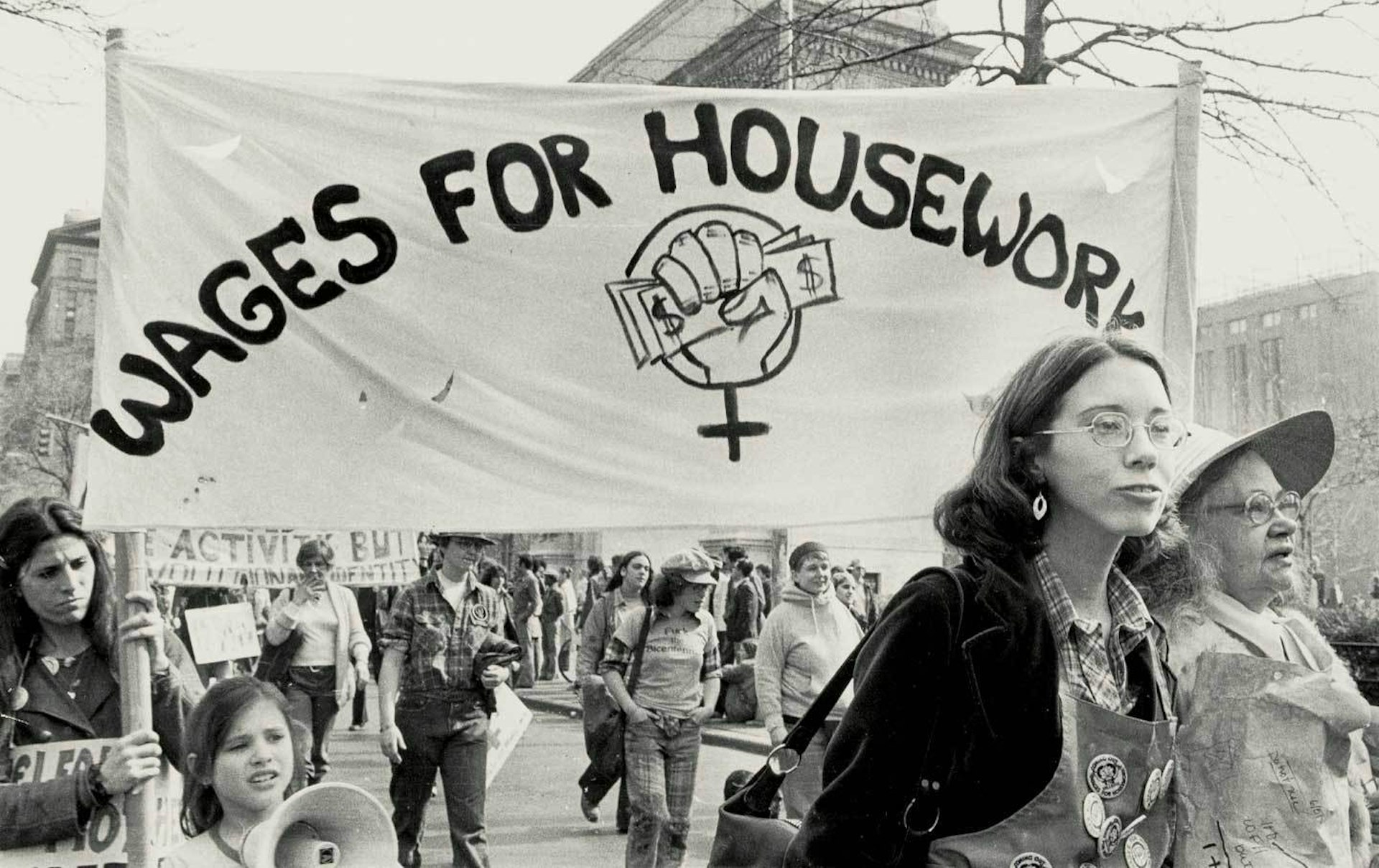

The story of Phở mile is a story of resistance. Following the communist takeover of South Vietnam in 1975, millions of refugees took to the seas in small boats to flee the repressive new regime and potential incarceration in one of the ruling party’s “re-education” camps. Hundreds of thousands died at sea. The UK government initially refused to accept the Vietnamese evacuees, with Margaret Thatcher warning ministers “there would be riots on the streets” if they were given council housing.

However, many local authorities, working with NGOs, welcomed and supported the UK’s initial quota of 10,000 refugees. Under the government’s tough dispersal policy – designed to prevent “ghettos” and “resentment” from locals – the arrivals were split up across the country, and limited to just a few families in each town. Despite the state’s interventions, Vietnamese people still gathered together. Now there are more than ten restaurants on Kingsland road.

According to Pierre, “Centre 151 helped many refugees feel less lost and isolated – it created a family away from home.” It provided essential welfare and resettlement services for the arrivals. While the decline in council funding over the last ten years has restricted its activities, it still hosts performances and arts events in its main room, and has a therapy room downstairs. A short stroll from Phở mile, the organisation – housed in a loaned church building – runs a Phở lunch club on Saturdays. It’s £5 a bowl. Walk through its doors, and you’re instantly hit with the hallmark Phở aromas of star anise and Thai basil, and the familiar sound of a bundle of chopsticks being run under a tap. On an average day, you’ll find groups of men huddle around tables, nattering while their wives did aerobic dances to Cantonese tunes in the centre of the room.

“Our regulars at the Phở club are mostly elderly,” says Centre 151’s resident chef Ha Nguyen says. “They come when their children have grown up and don’t live with them anymore. They want to come here and enjoy it, talk to their friends and eat Vietnamese food.” Ha, who left Hai Phong in 1990 following a spate of job losses in her village, tells me her journey to Britain was fraught with challenges. “I was pregnant, so I was sick all the way from the airport! Although we met many friendly people, it was really hard at first … everything was different from my country.” The centre is both a meeting place for those hungry for a taste of home, but also grounds Vietnamese people in the weekly routines they would have had in their home country.

My Pham, who co-owns Nom Nom and its sister branch Nem Nem with her husband, says: “At the beginning, we didn’t like London, as it was so expensive and we didn’t have friends. But now it feels like home. You can do alright here if you work hard.” Vietnamese people in the UK travel far to her restaurant just to eat bánh cuốn – steamed rice rolls – a notoriously difficult dish to make at home. She explains how you have to lay the batter very thinly and use an industrial-size steamer to get it right. When her husband Anh started out 20 years ago, he had never cooked before. He learned by watching his mother and videos online. After his father was diagnosed with cancer, Anh shifted the menu focus to vegan, healthier options.

“Most of the restaurants on Phở mile are family-run … we put our hearts into it,” says My. Even so, My, who also owns two nail salons, is wary of not pressuring her children to take over the business after they’re gone. She hopes they’ll keep all their job options open. “When they grow up, it’s their choice. But now I want them to start from zero and try their best in school. I want them to chase their dreams. I don’t want to force them to follow my steps.”

As Palluet highlights, Vietnamese people are more than just their trades, and mustn’t be pigeonholed in nail salons and restaurants. “Once you dig further, and meet people around Hackney, you see they are doing lots of amazing, creative things,” he says. The Van Huynh dance company, based at Centre 151 and founded by dancer and choreographer Dam Van Huynh, is one example of how the second generation of Vietnamese migrants are carving new paths, while embracing their community’s legacy.

Anna Nguyen, artist and community producer at the Museum of the Home, reinterprets and celebrates our forebears’ traditions in her upcoming audio-dining work Sonic Phở. Food is the thread. “My mum was dropped in the middle of the countryside outside Leeds,” says Anna. “The first thing that made her realise she was estranged from this land was the food. ‘Where’s the Nước Mắm?’ she would ask. For my parents, food wasn’t just a cultural tradition, it was survival. It was also an anchor to home.”

Georgina Quanch is a journalist at the Financial Times. Follow her on Twitter.

Home Away From Home is our series celebrating diaspora communities across the UK. See the rest of the series here.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.