How political correctness at university is threatening student art

- Text by Adam White

- Photography by Ashley Powell

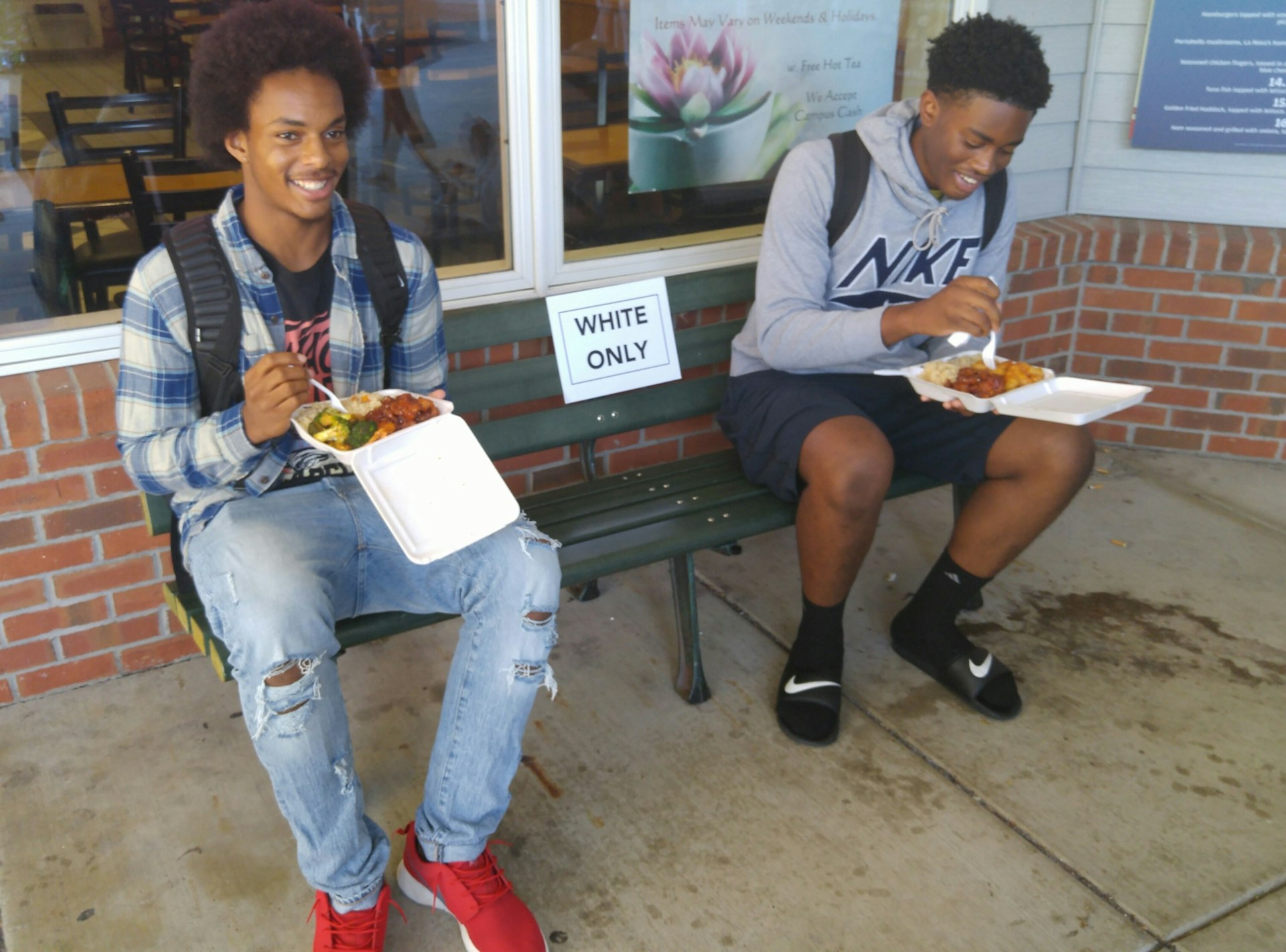

In mid-September, University at Buffalo students walked onto their campus to discover signs had been pasted near an array of bathrooms, benches, water fountains and elevators, some reading “White Only”, others “Black Only.” Given the opportunity to launch a public art project as part of her “Installation: Urban Space” class, graduate art student Ashley Powell decided to tackle her country’s rich history of racism. It’s a theme that permeates all of her artistic work, and has only grown in relevance after a series of high-profile killings of black Americans at the hands of the police.

But in a college climate described by The Atlantic as home of ‘the new intolerance’, Powell was met with outrage. Even when Powell’s intentions were made clear, her work was described by some as “an act of terrorism”, while others had determined that there was no valid artistic explanation for her work. Students told the campus newspaper The Spectrum, “you should know racism isn’t art, it’s a reality and traumatizing.” A white student was similarly quoted as saying that it was appalling to see such signs in 2015, and that “even white people were offended.”

Despite the backlash, Powell has no regrets about exploring racial discrimination through her piece, titled ‘Our Compliance’. “My own experience and the experiences of my peers have always driven me as an artist. The issue of race has always been so palpable for me, even when I was a very young child. Most of the time as a non-white youth, it becomes evident very quickly how you fit into the world around you. We begin to feel our skin colour very early on. I cannot cope with the fact that my skin colour negatively dictates, adulterates, perverts, and ceaselessly seeps into so many experiences, opportunities, and aspects of my entire life. It’s a reality that affects every single person in our society, and it is unacceptable.” She continues, “This has been, and may unfortunately always be, what drives me as an artist.”

In a statement Powell released to The Spectrum shortly after ‘Our Compliance’ went public, she argued her work directly involves “non-white suffering”, and that clarity and change can only come about as a result of public discourse. “I do not believe that there can be social healing without first coming to terms with and expressing our own pain, rage, and trauma,” she wrote. “For anyone who is questioning my actions on the basis of the pain they caused, I will say that this is the nature of my art and this is the nature of social change.”

Where Powell’s work is inspired by race, the work of London-based artist Daniel Sachon is inspired by sexuality. A student at Central St. Martins, his work blends unapologetic sex and violence with traditional commercial beauty. His photography includes a nude woman in ecstasy cradling an enormous bottle of perfume, along with an arresting triptych featuring a wounded woman piercing the camera through blood-soaked eyes. He isn’t afraid of his work inciting polarising views. “I’d rather someone come into my show and said they hated every single piece, than have somebody walk in on their phone, walk out, and not really take it in.”

‘Chanel to Bed’ by Daniel Sachon

But he too bristles at the idea of kneejerk reactions threatening his entire output. “As an artist, you want to hint at your point and then lead your viewer there. And sometimes people don’t take that in. It’s that whole quick judgment, and people need to realise that art needs time to breathe.” And without complex ideas, he argues, there’s little there. “I like to do things that people think will be one thing, when in fact they’re the other. It’s that idea of provoking. I think that’s what art is. If you’re not provoking something, then it’s pretty much just wallpaper. And that’s boring.”

Much has been made of the rise to define university campuses as ‘safe spaces’ and the student-led censoring of provocative ideas, from demands for faculty firings at Yale to the attempts to ban various writers, activists and thinkers from British universities for expressing controversial viewpoints. But while it’s nothing new for calls to be made to block controversial art, it’s a relatively new phenomenon to see young people at the forefront of enforcing political correctness. With students typically the proponents of creative expression and the tackling of challenging subjects, recent years have witnessed a sea change. The crotchety Mary Whitehouse figure of old has now been replaced by a young whippersnapper with a placard and a clipboard.

Race, sex and politics have historically been irresistible for young artists, turning complex themes into acts of artistic merit. For creatives wishing to continue tackling heavy themes and questioning social morals, it’s a marked concern that they have become part of the chorus of voices drowned out by those who have determined what is ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’ material.

“Nigger Dolls” by Ashley Powell

Most of this new form of student activism stems from positive intentions. The desire to make people comfortable and secure in their environments is an entirely valid one, as is ensuring an inclusive campus where all voices are granted equal weight. But by pre-empting hypothetical offense by removing any potential chance of upset, or banning artistic endeavours that have cultural blind spots, personal growth is halted, history is ignored, and educational opportunities are squandered. It’s therefore unhelpful to abruptly cancel a production of The Vagina Monologues because of its lack of trans references, as Mt. Holyoke College did earlier this year, denying students the experience of watching and challenging one of the most culturally significant theatrical productions in recent memory.

But the concept of challenging ideas has fallen in popularity in student culture. There’s a newfound reluctance in higher education to express critique through dialogue, but rather through a more finite, dictatorial shorthand. It’s certainly understandable. The first generation to have come of age during the rise of social media has now reached adulthood, and it’s not an enormous leap to suggest that a generation raised on Facebook unfriending, firewalls and blocking are more eager to apply internet logic to the real world around them. But not only does it jeopardise free expression, particularly in the arts, it does a disservice to a generation of young people rendered ill-prepared for the realities of adulthood, where opposing views, personal and professional disagreements, and plain human ugliness will continue to thrive and now potentially go unchallenged.

However, while it’s undoubtedly concerning, it hasn’t necessarily deterred the artists on the front line of university politics from continuing to pursue complex themes in their work. In spite of the reaction to ‘Our Compliance’, Powell refuses to alter her artistic focus. “It only affirmed my motivations. It served as an overt and tangible example that the work we do as artists is crucial, and may even need to be practiced more fiercely than ever before.”

Daniel Sachon’s Disruptive Innovation runs December 10-17 at the Londonewcastle Project Space.