Whatever the outcome, the EU referendum has been an uncomfortable wake-up call

- Text by Marie Le Conte

- Illustrations by Laurene Boglio

“And how’s Britain doing?” is a question I hear roughly once a month, whenever I call my grandmother in France. Ever since I moved to London nearly seven years ago, we talk every few weeks, and once she’s made sure that I’m still capable of feeding and clothing myself, we move on to current affairs.

As a one-woman UK news outlet, I’ve given my limited but captivated audience reports on two general elections, two referendums, a Labour leadership contest, and pretty much everything in between.

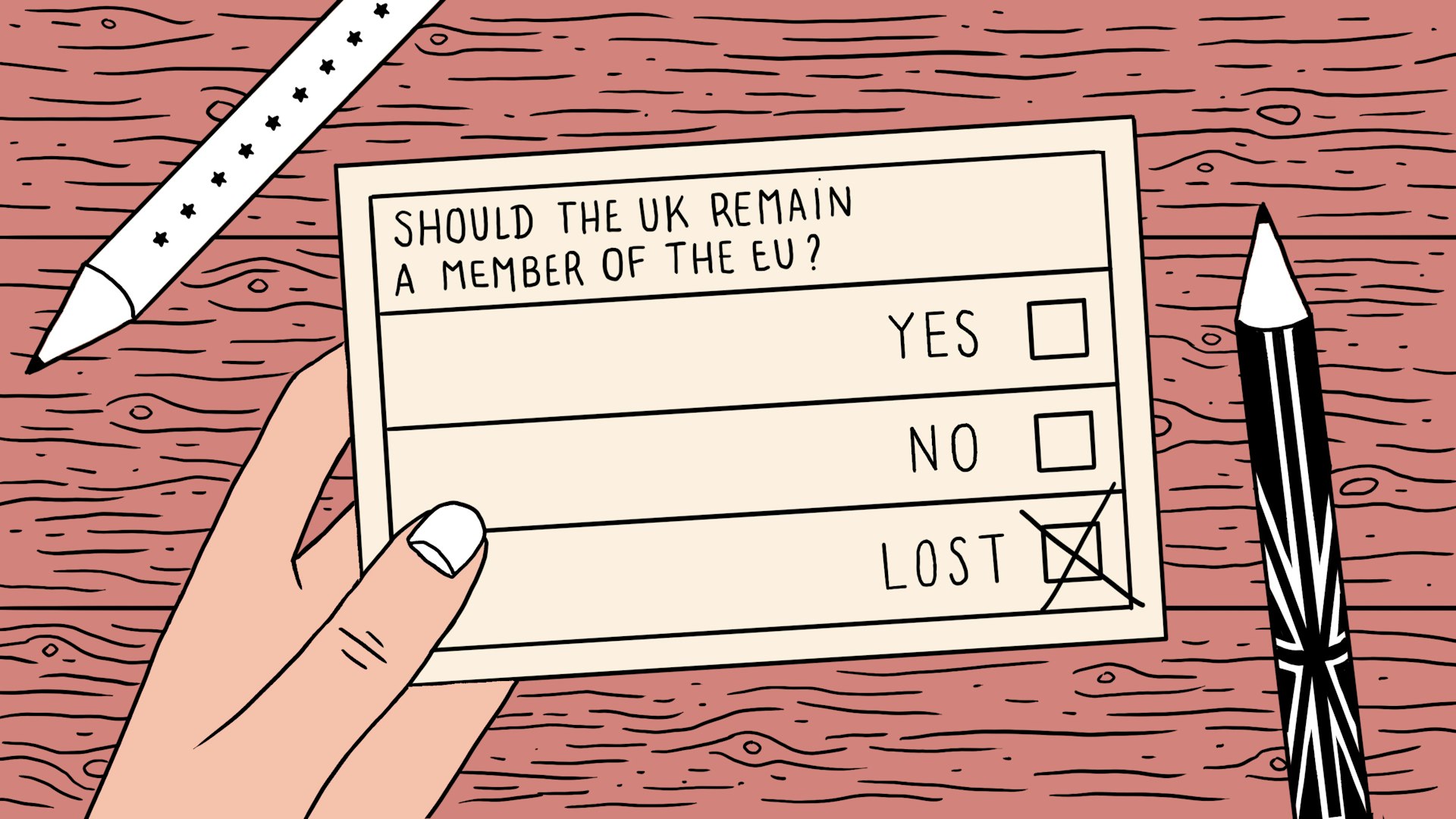

“And how’s Britain doing?”, she asked two weeks ago, expecting a personal analysis of the vote on June 23rd – but I was briefly lost for words. As someone who makes a living writing about politics, spends days scrolling through Twitter and nights drinking in and around Westminster, I’d found myself stuck in a curious paradox. On the one hand, I’d been eating Brexit op-eds for breakfast and going to bed dreaming of opinion polls, but on the other, I’d rarely felt this confused about a single political event. I’ve now come to realise that this may not have been an accident.

My life is, in many ways, the European dream. I’m French but moved to London to study, then decided to stay here to work; I’m writing this having come home from a drink with a Polish Portuguese friend studying in Aberdeen; our flat is currently quiet but I can normally hear my housemate gleefully blabber on in Danish on the phone from my room. I’m not naive enough not to acknowledge the fact that a bit of luck and a lot of privilege contributed to my pan-European lifestyle, but I’m also not obscenely posh, and neither are my friends.

I didn’t find it especially hard to integrate when I moved to England either, mostly because I did not see it as a truly foreign land; sure, there’s a Channel to cross, but it’s Europe, and therefore it’s my home. The idea of belonging – and identity – wasn’t ever an issue, therefore not something I’d ever thought about.

As a cynical Westminster watcher, I’d assumed that Cameron had committed to an EU referendum to make his backbenchers keep quiet, and make sure that his party could survive a slight Ukip swing in May 2015. I have, after all, friends from all sorts of backgrounds, whose allegiances are fairly well distributed across the political spectrum, but anger against the EU rarely featured in our nerdy pub chats. I honestly thought that the campaign would be a slightly blasé no-brainer, where the Eurosceptic views of some communities in the north of England would be quietly swept under the national carpet.

I was, it turns out, astonishingly wrong. Having London-dwelling friends from all sorts of political persuasions doesn’t mean being in touch with a whole country, as I’d foolishly never quite realised. When the Brexit tide took over large parts of England, it showed just quite out of touch I had been all this time, and how angry vast swathes of the population felt at being left behind. My microcosm was an exception, and what might be the majority had been kept silent until then.

It had never crossed my mind, exactly because of my background: while I may now spend time around people you reasonably could call the Establishment, I am, at heart, an immigrant from a moderately middle class background, who ended up where I am more or less at random. Though I may often find politics a bit dreary, and obviously quite out of touch with my personal reality, it still spoke to me. As a result, I’d clearly always underestimated just how alienated so many people were. The fact that the strength of the feelings being roused by the referendum baffled me was, I suppose, a wake up call.

The Brexit campaign has been tailored to those left feeling powerless by politics as usual; a campaign promising power to come back to these shores, a campaign conveniently ignoring any nuances, for the sake of uncompromisingly strong slogans. The EU isn’t really the drive behind the increasingly manichean atmosphere in this country but hey, it could be, and that’s enough for some. And after all, if you’ve not got much to lose, why not give it a shot?

What is conveniently not being mentioned by europhiles, however, is that people like me do need to share our part of the blame. Growing up in the cotton cloud the EU can be when at its best, I’d never stopped to consider how unique my situation was. I’d never really considered the fact that Erasmus was only ever going to be useful to those who actually make it to university, or that deciding to move to another country to study could only be an option to those who already spoke another language.

As it is, the EU project – the beautiful, romantic image of the EU I have – is only an accessible reality to a minority. It also isn’t all grey skies and dull bureaucracy, as some would rather see it. This middle-ground isn’t quite satisfying enough, however – in order for the EU to thrive, it needs to appeal to all levels of society, and provide the chances people like me were offered to everyone. As the Brexit debate has shown, the only other option is for people to retreat to their own scared and often scary nationalism. It doesn’t need to be like this – whichever way Britain votes on Thursday, this should be a warning sign to the EU: open up, or watch others shut themselves out.

Marie Le Conte is a freelance political journalist living in London, you can follow her on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.