Anger over unaffordable homes isn't self-entitlement, us renters are treated like shit

- Text by Abi Wilkinson

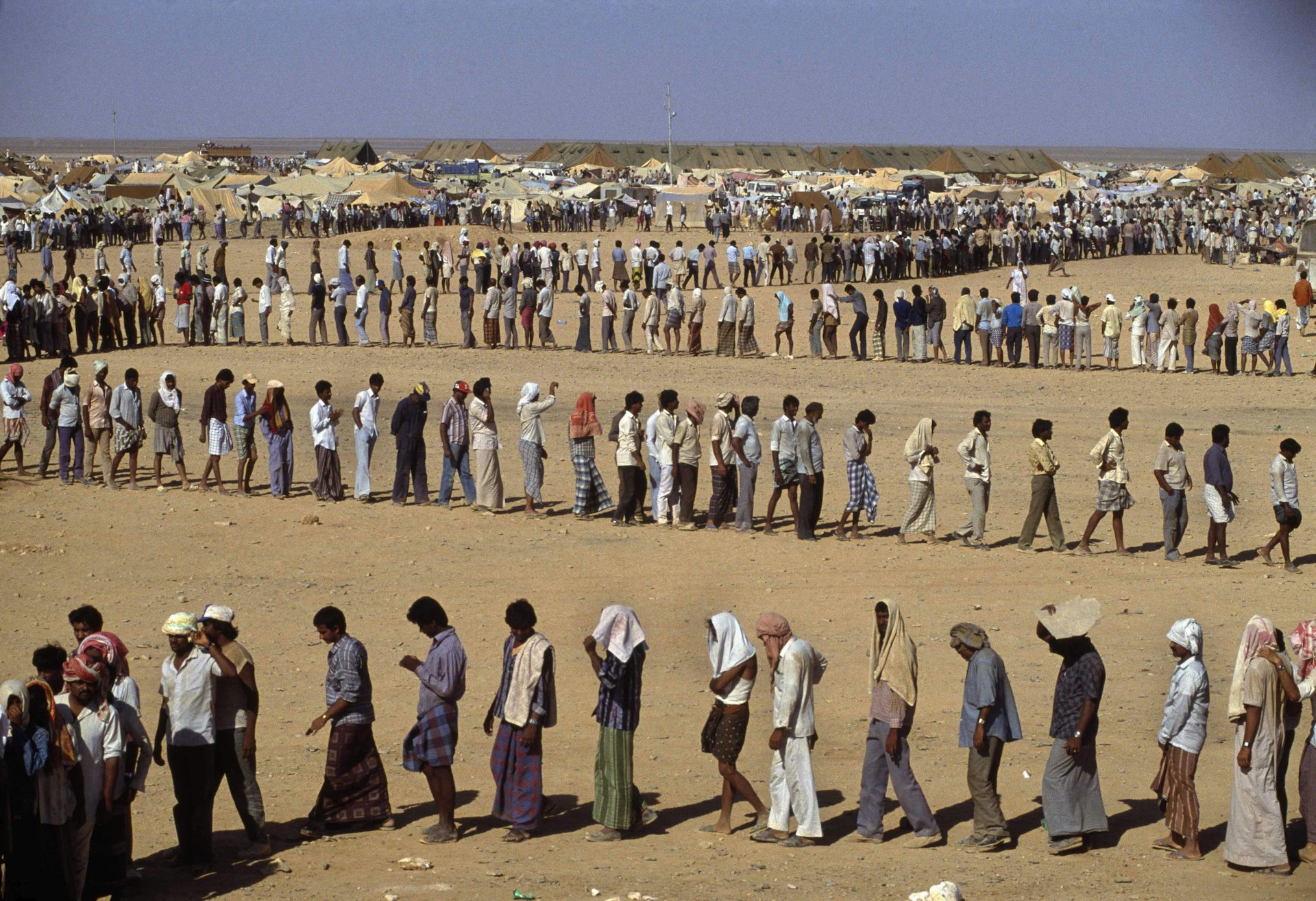

- Illustrations by Oliver Stafford

Do you want to know one of my biggest fantasies? The thing I desire more than anything, though it makes me blush to admit it in the cold light of day. What I want, what really gets me excited when I’m alone with my thoughts, is the opportunity to select and purchase a sofa. Not just a sofa, either, my imagination is wilder than that. Sometimes I dream about furnishing an entire apartment. Beds, wardrobes, a dining table, the works. Once, I even thought about refurbishing a kitchen.

You can draw your own conclusions about what this says about me as a person. The fact is, though, for someone in my position — 26, living in London and scraping a living as a freelancer — being settled enough to invest any significant amount of money in altering my living environment feels far more of an unrealistic, exciting fantasy than any kind of sexual scenario I could conjure up.

Maybe, as middle-aged homeowner Sean O’Grady argued in the Independent today, it’s my “sense of entitlement” as a young person that causes this “fetish of home ownership” and all of the things that come with it. I don’t think so, though. It’s true that owning a home isn’t a human right, but the desire for stability and security is a fairly normal human impulse.

Though the looming pensions crisis and social care cuts do make me worry about what’ll happen to me in old age if I don’t have property to cash in, ownership isn’t really the main issue. I’d feel far more positive about the idea of renting if the reality of it wasn’t so awful. This is why O’Grady’s comparison of the UK with Germany, where the majority of people rent and home ownership is seen as far less aspirational, makes so little sense. In Germany, renting isn’t shit.

Tenants have far stronger rights and the leases they’re granted are normally for an unlimited period of time. This means landlords can only evict for a handful specific reasons, such as multiple months unpaid rent or significant damage to the interior of the property, or because they want to move into the home themselves. In these circumstances, they have to give tenants notice between three and nine months in advance — depending on how long they’ve been renting the property. Landlords can also be fined if they demand excessive rent increases. In short, tenants have rights.

In a country like Germany, I’d find it perfectly possible to fulfil my nesting ambitions without having to actually own the building I was living in. Living in London, where 6-12 month leases are the norm and people are regularly forced to move at a moment’s notice because the landlord reckons they could make more money getting new tenants in, such a scenario sounds positively utopian.

As things are, many young people have no option other than to continue bouncing from place to place to escape unscrupulous landlords and prohibitive rent hikes.

Buying your own furniture feels risky when there’s no guarantee it will fit wherever I end up next, and moving is already hard enough when it’s just clothes, books and saucepans, so we’re stuck with whatever our landlords decide to bung our way. This might not be so bad if it didn’t often mean backache-inducing mattresses and appliances that are barely fit for purpose.

The worst thing, though, is the constant insecurity. The feeling that there’s no point ever getting too settled anywhere, because you’ll probably be forced to move before too long. This transience has knock on effects for all areas of our lives. It’s difficult to feel part of a community, to get involved in things locally or to form proper relationships with your neighbours.

While my situation could be far worse, I do think people need to take into account the psychological impact of housing insecurity when they talk about the “entitlement” of wanting to own a home. Young people aren’t greedy, we just want to put down roots and know we’ve got somewhere to return home to. Is it really fair to blame us for that?

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.