Mapping the squats, strip clubs and bars that launched punk

- Text by Cian Traynor

- Photography by Herb Lester Associates

To mark the 40th anniversary of punk, writer and cultural historian Paul Gorman has a created a guide that traces the squats, clubs and rehearsal spaces from which the phenomenon emerged.

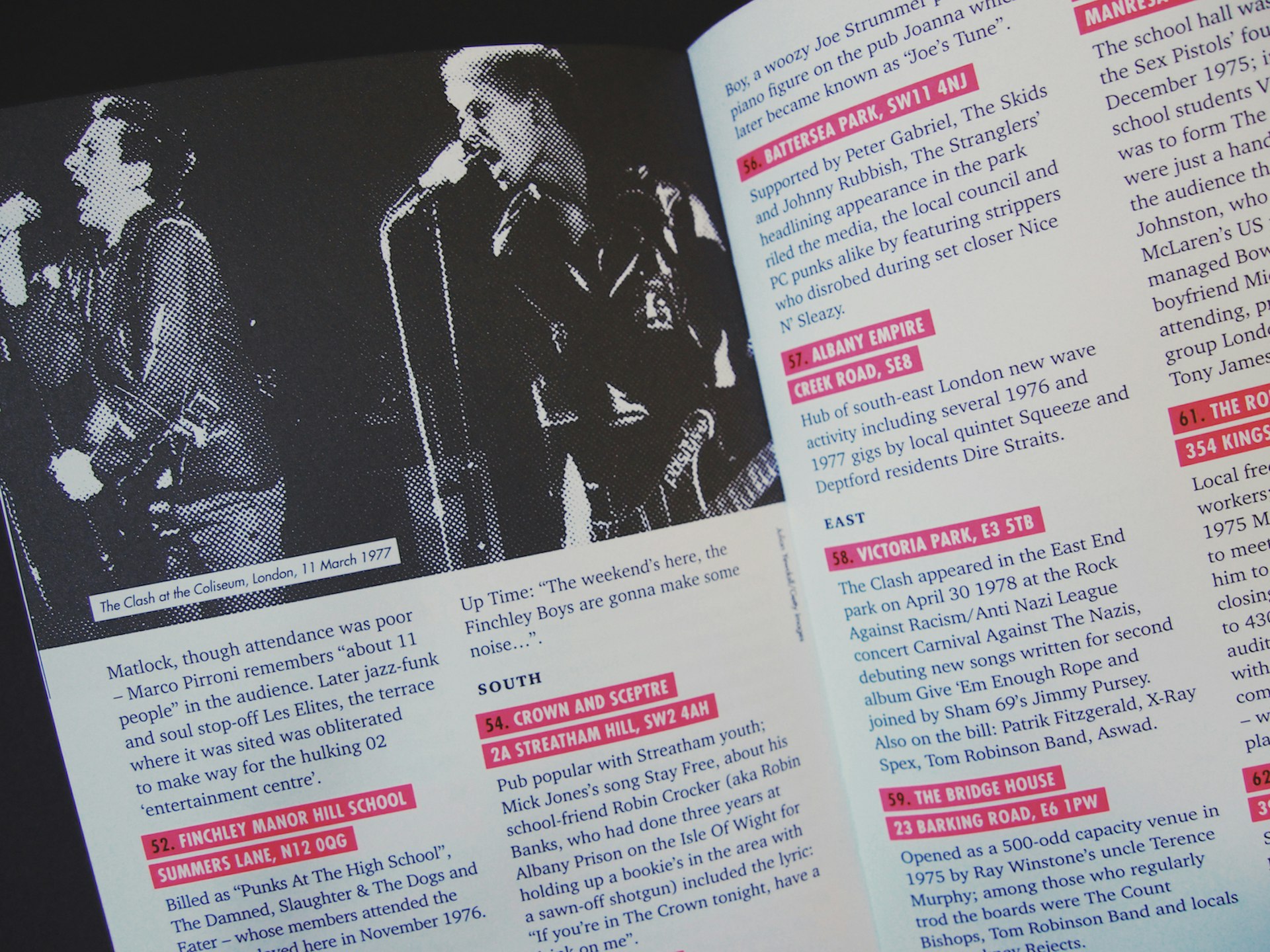

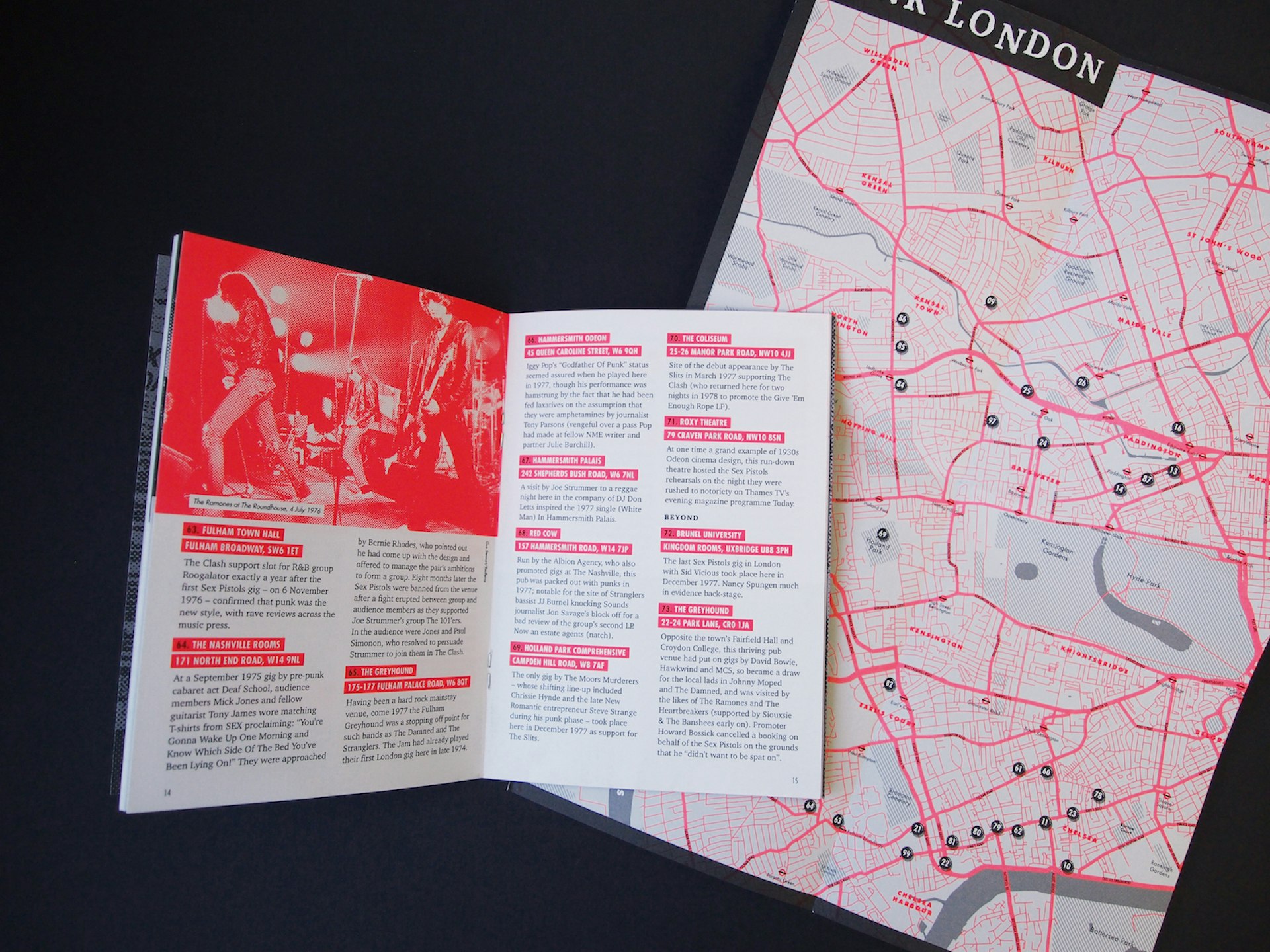

Featuring rare photos and drawing from in-depth research, Punk London is a map that pieces together the stories behind the music in a new way – through 111 locations that will always be connected to the subculture, whether they remain recognisable or not.

Why do you think the public’s interest in locations connected to punk has endured for 40 years?

Because this was hands-down the most exciting and out-of-control period in our post-war history – and it came out of London, so that’s reason enough for it to be celebrated. The hippie underground/’Swinging London’ [era] of the sixties turned out not to offer an alternative way of living but in fact were another iteration of consumer culture. Punk – for however brief a period – posed a very real threat to ‘normal life’ and acted like a virus which infected millions around the world. Even when the stylistic aspects were co-opted by the music, fashion, media and ‘lifestyle’ businesses, the attitude couldn’t be bought. Plus, it looked great!

And it came out of unlikely places: art schools, strip clubs, run-down cinemas, squats, derelict warehouses, council estates and the suburbs. These days those buildings on the map which still exist are largely unremarkable… but they contain stories both colourful and fantastic which combine to tell a secret history of London.

How much of this guide came from first-hand experience and how much of it through research?

Mostly research – I am very keen on tracking down first-person testimony – though there is an overlay of personal experience. I was a 16-year-old Londoner in 1976 and had a tangential relationship to what was going on, mainly as someone interested in the clothes, music and media – which ranged from the high–end press such as Harpers & Queen to fanzines such as Sniffin’ Glue.

Essentially the map is my view of the places which were important during the period and hopefully it will also appeal to those who know nothing about punk or London at that crucial time. Where necessary, I tried to spice up info on the familiar addresses with little-known nuggets. For example: the Marquee in Soho was where the Sex Pistols videos were filmed, or pointing out that at the same time as Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious were living at Chelsea Cloisters, one of the other occupants in the apartment block was Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd.

What surprised you the most along the way?

The fact that the area around Shoreditch contains not one address from the 111 on the map. I remember that area: it was industrial and not of interest to those living out the lifestyle of clubs, venues, fanzines, fashion and record shops, etc. Creativity in London in that period was centred in Soho and west London: essentially Notting Hill and Chelsea, which these days are mostly cultural deserts. The addresses on a map of creativity in 2016 would be glutted in east London and places like Peckham, so it was a lesson in the mutability of our city which can go from radical to reasonable in a generation.

How many of the locations are still in the same form today?

Quite a few but several are under threat from the rampant property development we are experiencing. Still, right now there are pubs frequented by punks such as The Cambridge on Cambridge Circus, The Ship in Wardour Street and The Hope & Anchor in Islington. Then there are venues such as the 100 Club in Oxford Street, The Roundhouse, Dingwalls and the Music Machine (now Koko) in Camden as well as, of course, the place where punk was incubated by the late Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren: 430 King’s Road, which is now his ex-partner Vivienne Westwood’s shop Worlds End.

How many locations seemed dramatically removed from their purpose during the punk era?

Virtually all of them, but the most telling for our times is the top floor of 107 Charing Cross Road. On November 6th 1975, this was the refectory of St Martin’s School of Art and played host to the debut gig by the Sex Pistols with about a dozen people in attendance. The plug was pulled on them four songs in after an altercation with the headline act, so they were set on the path to infamy. Today that space is a £10m luxury apartment above Foyles bookshop. How times change, eh?

Do you think London retains any of the cultural vibrancy of that time? Or has it changed beyond recognition?

I’m not a great one for the good old days. Despite the high cost of entry and the tough breaks for young people just starting out, as a London lifer with deep family roots in the city I’m pretty sanguine about the changes which have occurred over the last four decades. We are still the capital of cool, with a vibrant youth culture from British rap to fantastic graphic design. But this is largely online so people believe that since there isn’t a physical manifestation of it – in the form of indie boutiques or whatever – then it’s not happening. But believe me, it is: under the radar. One just has to dig.

What is your most enduring memory experienced at any of the locations on the map?

I was in The Roebuck pub at 354 King’s Road (now a branch of Byron) the night that Johnny Rotten was auditioned by the Sex Pistols in August 1975. I was not by any means part of that crew but, even at 15, I knew from hanging around that area and encountering people like Malcolm McLaren that there was something in the air and that my life was about to change. I didn’t realise though that so would the lives of many others, but at least I can say: “I was that soldier.”

Malcolm McLaren predicted that punk would come back in different forms again and again. Do you recognise the thrust of it in contemporary culture?

Sure, there are many examples: from magazines such as Mushpit and the independent label High Focus, as well as Pussy Riot and Anonymous. They are the very definition of punk, which is to be non-conformist, anti-authority, anti-corporate and do-it-yourself. McLaren’s impulse was to disrupt and cause chaos – these and many other activist organisations abide by that.

You don’t have to go to their extremes… but one wonders: if the chips were down, what would you do? There are many ways to live your life independent of the mainstream. I don’t have a TV, follow sport or music industry shenanigans, buy fast fashion (or any fashion, come to that), indulge in celebrity culture or run a car any more.

I make sure I watch my carbon footprint, recycle, respect minorities, accept the rights of others to express their opinion, support animal rights and unions; I try to expose hypocrisy and generally do the right thing. These are all tiny acts in themselves, but for me they’re are a way of making a stand – however small – against the ghastly spectacle of post-capitalist consumerism and globalisation. If that’s punk, then so be it.

Punk London: In the City 1975-78 is published by Herb Lester.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.