A secret family history, reconstructed in the present

- Text by Diana Markosian

- Photography by Diana Markosian

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

I grew up in a house of secrets. Every family has a story. You grow up with your version of it, but as an adult that narrative shifts beneath your feet as more facts are revealed.

At 27, my mother told me she was a mail-order bride. She didn’t phrase it that way, exactly; rather that Eli, the American who became my stepfather, was a man who had written to her when we lived in the former Soviet Union. It was because of Eli that she put me and my brother on a plane when I was seven years old, bound for a new life in California – away from my real father, who never knew where we had gone – to a town we had grown up watching on TV: Santa Barbara.

I was born in Moscow but when the Soviet Union collapsed, we lived between Armenia and Russia, spending a few months here and there. Armenia was at war with Azerbaijan at the time, so there was no electricity or water. I remember my mum would dress me in all of my winter clothes and we would just sit there. Life in Moscow wasn’t any easier. My parents, both professors, sold Barbie-doll dresses on the Red Square, while my brother and I would spend our mornings picking up bottles which could be exchanged for bread.

I was born in Moscow but when the Soviet Union collapsed, we lived between Armenia and Russia, spending a few months here and there. Armenia was at war with Azerbaijan at the time, so there was no electricity or water. I remember my mum would dress me in all of my winter clothes and we would just sit there. Life in Moscow wasn’t any easier. My parents, both professors, sold Barbie-doll dresses on the Red Square, while my brother and I would spend our mornings picking up bottles which could be exchanged for bread.

My childhood memories are all about ‘before’ and ‘after’. There’s me, my brother and mother carrying water up the stairs, huddling around candles playing cards, waiting for my dad to show up – which he seldom did. Then there’s our life in America, with Eli, a man who opened up another world. There was no in-between. I remember begging my mother to tell me about my father and there were no stories. She cut him out of every family photograph.

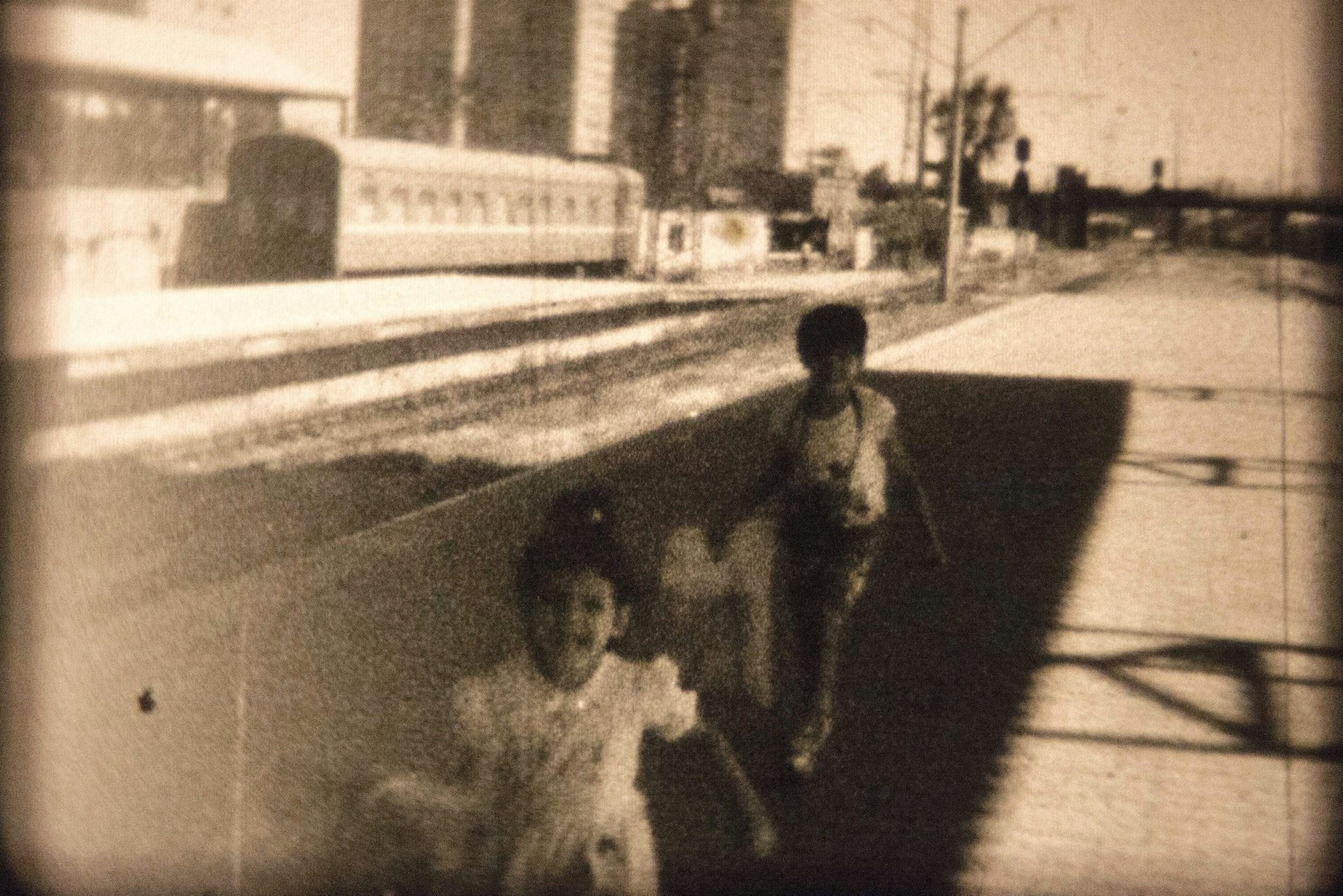

It took two decades to find the courage to track down my father. In reconnecting with him, I saw a different version of my past, through his eyes and the Super8 films he shot of us as children. In one of them, my brother and I are running outside our apartment block, carrying plastic bags that contained all our belongings: some crayons and school papers. It re-enforced a memory I had begun to think wasn’t real: that our life together, which ended so abruptly, was real.

That sudden rupture in my past has never left me. I needed a way to process what happened to that little girl. Santa Barbara, my subsequent project, became my way of doing that. To reconstruct and reimagine the past, I worked with the original writer of Santa Barbara – the soap opera that inspired my mom to move to America – and created a script, casted actors to play my family, and photographed them as we shot a film.

That sudden rupture in my past has never left me. I needed a way to process what happened to that little girl. Santa Barbara, my subsequent project, became my way of doing that. To reconstruct and reimagine the past, I worked with the original writer of Santa Barbara – the soap opera that inspired my mom to move to America – and created a script, casted actors to play my family, and photographed them as we shot a film.

The shoots started in Santa Barbara, with a set in Hollywood built to look like our original Soviet apartment, but something didn’t feel right. I was shooting these cinematic portraits on set and just couldn’t see my mother’s story in them. It wasn’t until she came on set that I understood why. She said, “Where am I Diana? Our home was never this nice.”

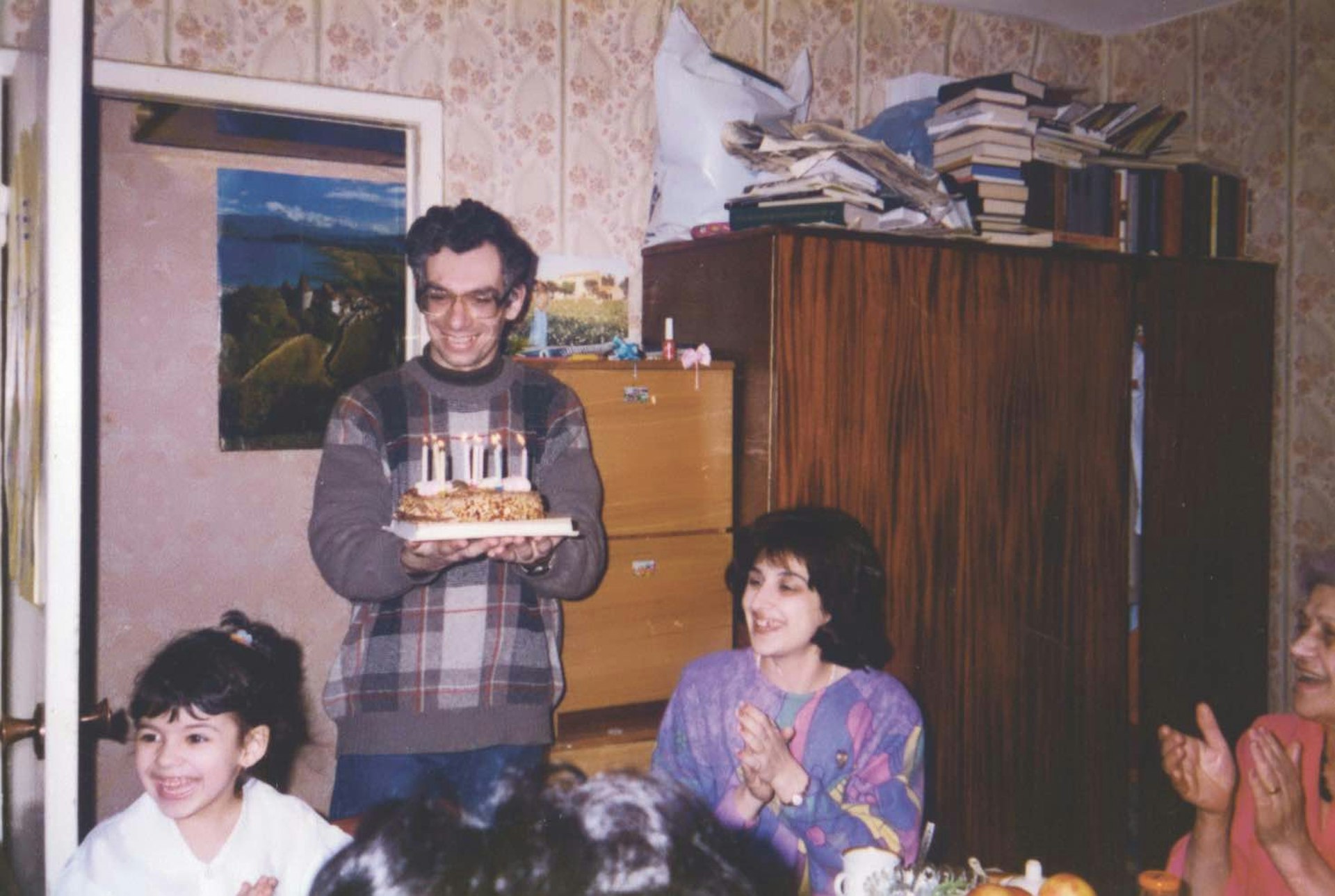

I realised I had to get closer to the truth. We travelled back to Armenia, to the actual apartment I grew up in, and reshot the first scenes there. For the stills, I started shooting on my mother’s 35mm camera from the 1990s. Things fell into place.

Suddenly, I saw myself and my family in the individuals who were playing us. And for a split second, nothing was taken away from me: I had everyone back. We were in my home and it was my seventh birthday. My dad hadn’t been home in a month and here they were arguing. It felt so real in a way that I could never have imagined, like reading a book you’ve read before. You know the ending, but you need to process those first chapters to truly understand what happens in chapter eight. It was like someone had pressed rewind: I had a chance to go back and reread chapters one and two.

Suddenly, I saw myself and my family in the individuals who were playing us. And for a split second, nothing was taken away from me: I had everyone back. We were in my home and it was my seventh birthday. My dad hadn’t been home in a month and here they were arguing. It felt so real in a way that I could never have imagined, like reading a book you’ve read before. You know the ending, but you need to process those first chapters to truly understand what happens in chapter eight. It was like someone had pressed rewind: I had a chance to go back and reread chapters one and two.

The trigger for this project was the idea that every story has multiple sides. When I found my father, I resented my mom for what she had done and couldn’t find any room for empathy. I realised I had to revisit our story from my mother’s perspective – taking her side and walking her footsteps. It was this hope that maybe through the work I would learn to love her.

My mother essentially chased an ‘American Dream’, but it was her dream and never mine. I was just carry-on luggage. And when you start to understand that – that you were taken on a journey, you never chose to go on one – it just hits a little harder. I had to step out of that narrative and into my mother’s story of standing alone at the airport with two kids, not knowing who was going to meet us. Putting myself back in that old apartment – the home that felt so massive when I was a little girl, but that could barely fit our family – was the first step forward.

My mother essentially chased an ‘American Dream’, but it was her dream and never mine. I was just carry-on luggage. And when you start to understand that – that you were taken on a journey, you never chose to go on one – it just hits a little harder. I had to step out of that narrative and into my mother’s story of standing alone at the airport with two kids, not knowing who was going to meet us. Putting myself back in that old apartment – the home that felt so massive when I was a little girl, but that could barely fit our family – was the first step forward.

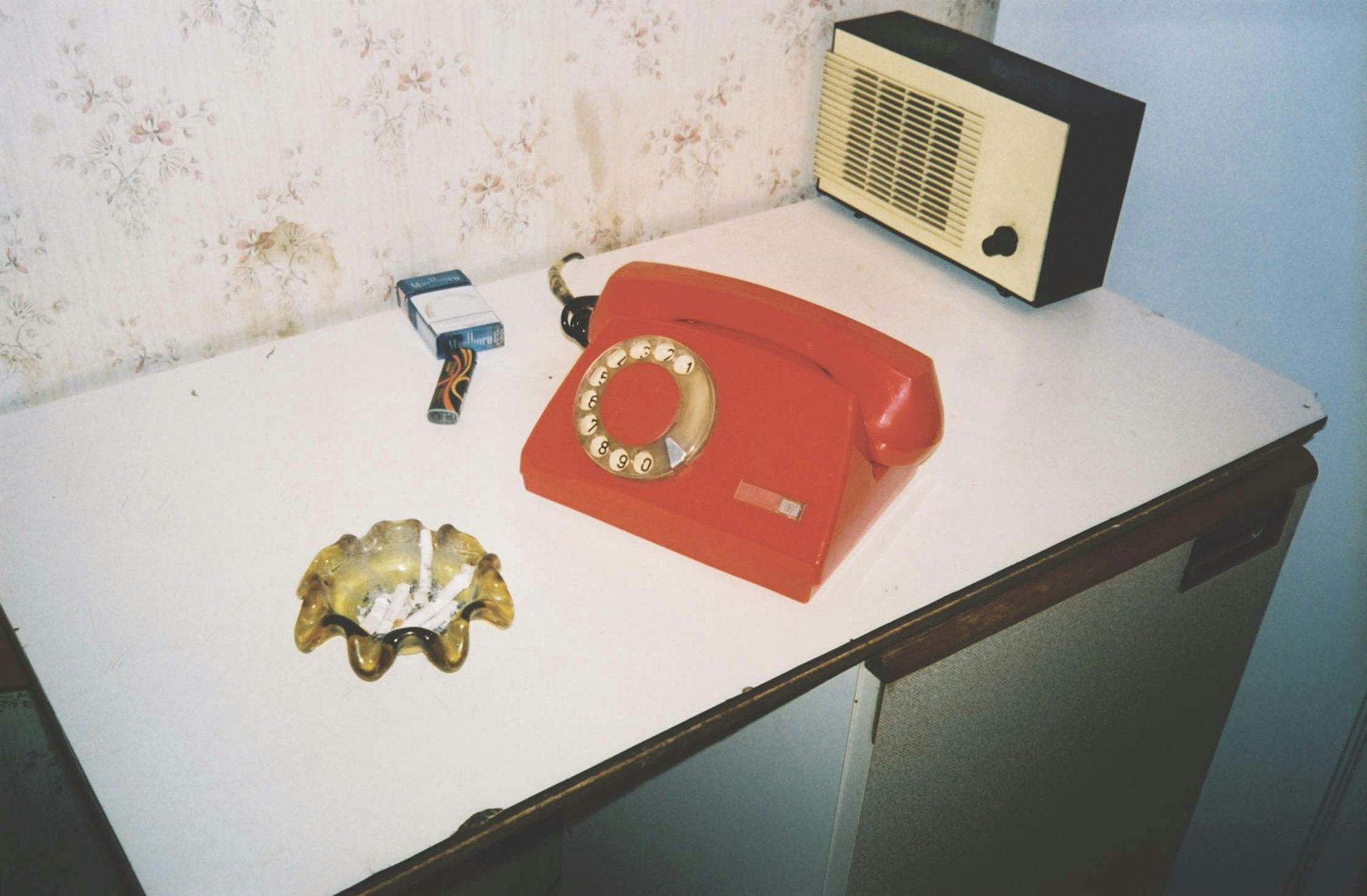

‘Home’ felt like a prison for my mother. This project took me a step closer to understanding that desperation and isolation: she later told me it felt like she was drowning. Our only connection with the outside world was a TV with a single station. And for my mother that was a form of escape. And then that escape became a reality.

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

See more of Diana Markosian’s work on her official website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.