The stateless athlete running for her life

- Text by Gabrielle Weiniger

- Photography by Violeta Moura

Growing up in the shadow of Eritrea’s highest mountain, the stony Emba Soira, Rahel Gebretsadik developed a thirst for the extreme.

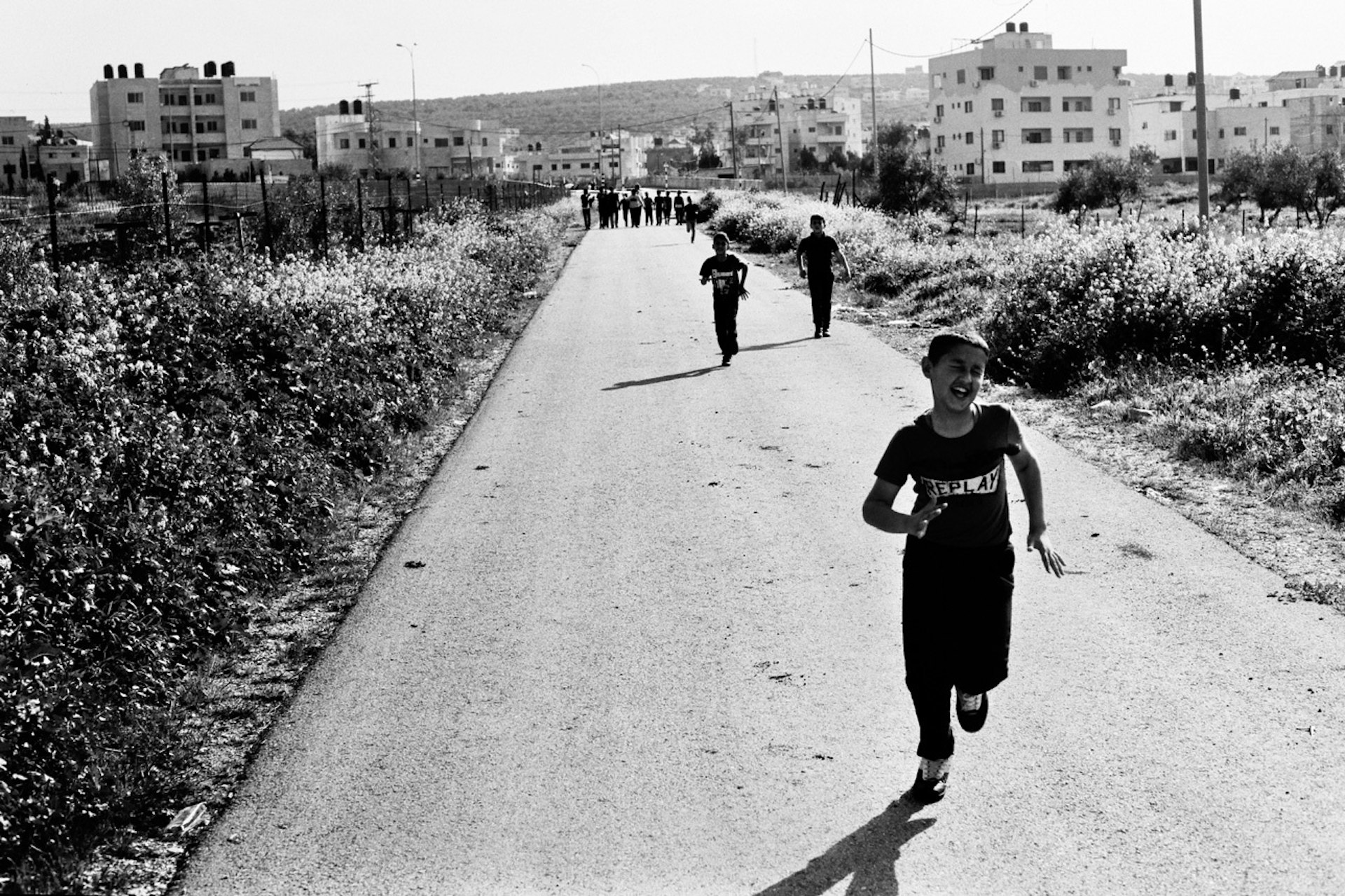

At 16 years old, she runs twice daily – at the crack of dawn and at the dim of dusk, preferring cross-country to track – earning her a reputation as the fastest girl in the land.

But Rahel isn’t running in the highlands of her home country. She’s swapped the forest-covered mountains for the bare streets of Tel Aviv.

The journey that brought Rahel to Israel is a hard-edged memory. She recalls carrying her young sister on her back while she, her mother and seven siblings made the arduous trek across the Sinai desert, sharing rations with 34 others.

Rahel doesn’t know what happened to the friends she left behind, or if they ever rebuilt the rough-stone houses destroyed during the war with Ethiopia.

All she knows is that they had to escape a brutal regime that tortured members of her Christian community.

“I loved my school… but my parents took the decision to leave and I had no say in it,” she says, toying with a black-beaded bracelet that spells out her name in Hebrew on one side, the bright primary colours of the Eritrean flag on the other.

Rahel’s father and two brothers were waiting for them in Israel.

Reunited, she was enrolled in the Bialik-Rogozin School of south Tel Aviv, once a school for local Israelis, now a facility for at-risk youth – new immigrants, refugees and children of foreign workers – which reflects the changing ethnic makeup of the neighbourhood.

Rahel credits her civics teacher, Rotem Genossar, for spotting her talent. “I realised I could run when they put me in a race during sports class,” she says.

But while she could run fast, she couldn’t run hard, exhausting herself because she couldn’t pace properly.

The need to hone Rahel’s natural gift was the inspiration for the Alley Athletes team, a sports club founded by teacher Rotem and lawyer Shirith Kasher a year after her arrival in Israel.

It now consists of 70 athletes from 15 countries, but Rahel has outrun most of them, becoming the only girl in the team who’s reached European level – alongside 10 boys.

In February, the boys will compete in the European Champions Club for the first time. With Rahel’s asylum application to stay in Israel still being processed, she doesn’t know if she’ll be able to join them.

Tens of thousands of Eritrean and Sudanese nationals have applied for refugee status in Israel over the past decade, but only a select few have been recognised. Those living in Israel without residency are barred from working, unable to access state health and welfare services.

They’ve been called ‘cancerous infiltrators’ by members of the Israeli parliament, effectively alienating refugees from public discourse.

There’s also a looming threat of arbitrary detention at Holot, a fenced-off facility in the desert – the same desert many refugees crossed to escape their home country.

The summons to Holot can come at any time, regardless of the status of their asylum application – a policy local activists say is intended to force refugees to take the ‘third-country option’: a free flight and pocket money to leave Israel for Uganda or Rwanda, where their safety cannot be guaranteed.

Rahel hopes her special status as an athlete, combined with local media attention, will help push forward her asylum application.

Without it, she’ll be forced to surrender her medals to runners who hold Israeli citizenship once she turns 18 – even if she crossed the finish line ahead of them. She will also be unable to represent Israel internationally, or at the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

“We just want to win competitions. And we have won. Right now, they only let us win awards because we are under 18. What will happen next, when we grow up and want to join the adult team? We can’t be awarded even if we win? We will always remain inferior,” Rahel has said to Israeli media.

It’s unclear if this media attention will work in Rahel’s favour. Her only hope may be to join the Refugee Olympic Team for stateless athletes, which made its first appearance in Rio this year.

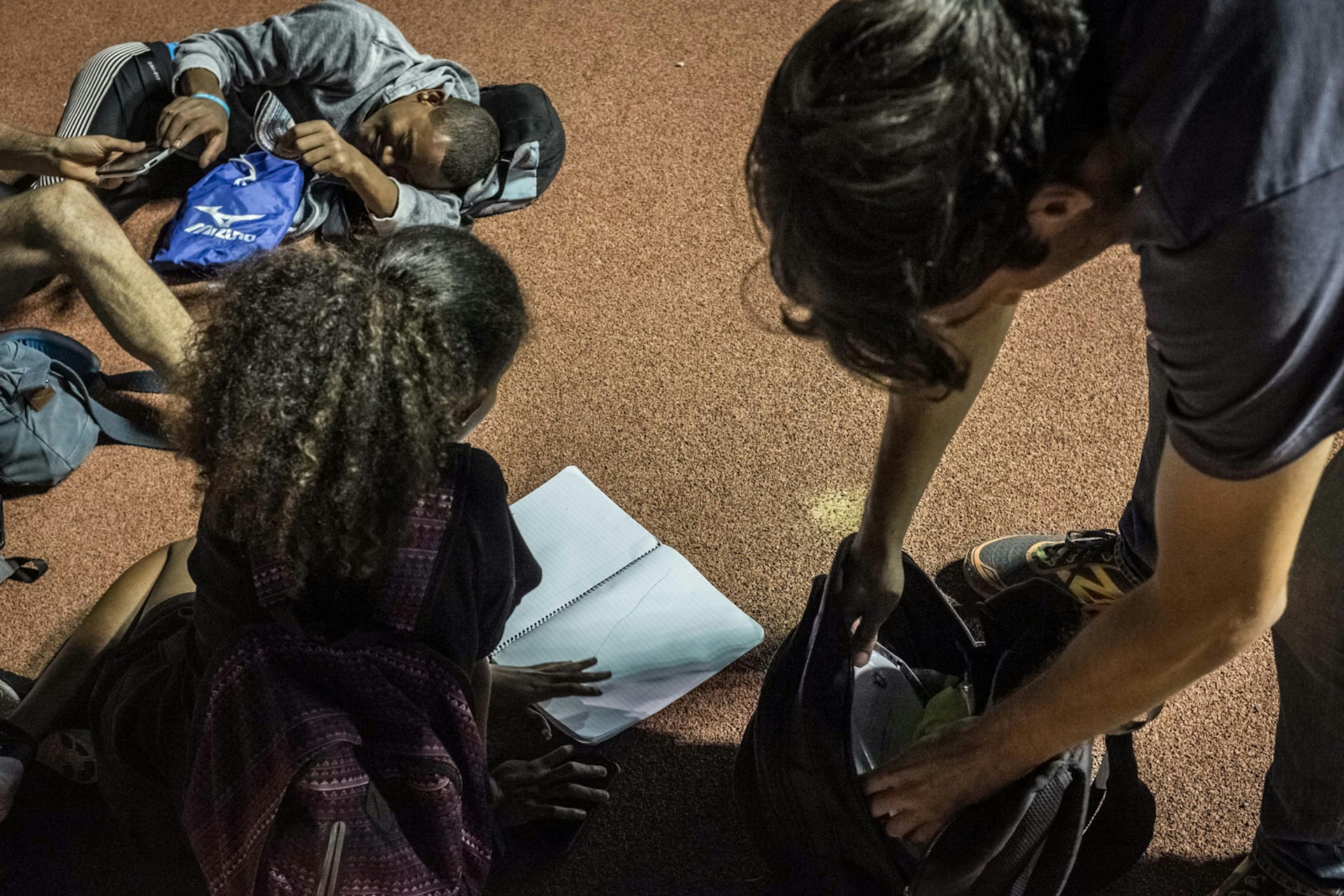

Still, the club amounts to more than just a track and field. It’s the birthplace of her friendship group.

After training in the evening, they all go to a nearby Ethiopian restaurant and scoop up a shared dinner with injera, a greyish sourdough crepe that originates in the highlands of East Africa.

“Nigerians, Filipinos, Ethiopians, Palestinians, Eritreans – we all eat together,” she says.

“With such a mix of people here, I feel so safe. Everyone here is the same colour. From my community, or from other foreign communities, no-one here looks at you strangely. I feel like I belong.”

Once a week, Rahel has a day of rest from her regime. “Usually Christians worship on a Sunday but Saturday is the day of rest here because it’s a Jewish country, so we go then,” she explains.

While Tel Aviv mostly shuts down, the neighbourhood of Neve Shanan is filled with gospel music and sermons, chanting and clicking to psalms and prayers. For her family, freedom to worship as Protestant Christians isn’t taken for granted.

According to the Barnabas Fund, a Christian aid agency, a 28-year-old Eritrean student was arrested in 2010 for attending Bible study and died after being held in a shipping container for two years.

Persecution and forced conscription has led the UN to forbid the deportation of Eritrean nationals. But in Israel, temporary protection status has left many in limbo: a present without rights and a future without certainty.

Recent attention on the Alley Athletes has facilitated a much-needed discussion about the rights of young, gifted refugees; but a wider one is needed on the treatment and policies for those seeking a safe haven.

For Rahel, Israeli nationality is not the finish line – but it would certainly help. “I’d love to do the Olympics,” she says. “I don’t care which country I represent. Just let me run.”

This article appears in Huck 58 – The Offline Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop now or subscribe today to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.