Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and the rise of Mexican Modernism

In the early 1920s, a teenage Frida Kahlo met Diego Rivera while he was painting the mural ‘La Créación’ at the Escuela National Preparatoria, the oldest high school in Mexico. In his late 30s, Rivera was at the outset of a spectacular career, and was set to become one of the most prominent modern artists in the world.

“One day they asked me who I wanted to marry, and I said I would not marry,” Kahlo told Olga Campos in 1950. “But I did want to have a child by Diego Rivera.”

Though they never had any children, the couple married twice. Theirs was not an easy life, as Kahlo famously confirmed: “I have suffered two grave accidents in my life, one in which a streetcar knocked me down… The other accident is Diego.”

Yet for all their trials and tribulations, their legacy lives on, and is being celebrated in the new exhibition Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism from the Jaques and Natasha Gelman Collection. Featuring about 140 works, the exhibition explores their lives and love affair, while placing their contributions within the larger context of revolutionary Mexican art.

“Frida wasn’t originally an icon,” says Jennifer Dasal, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. “Though not unpopular or unknown during her lifetime, Frida was little recognised outside of the major art centres. Now has become an international cultural phenomenon, her face often adopted as a beauty icon, feminist, accessibility advocate, and Latinx idol.”

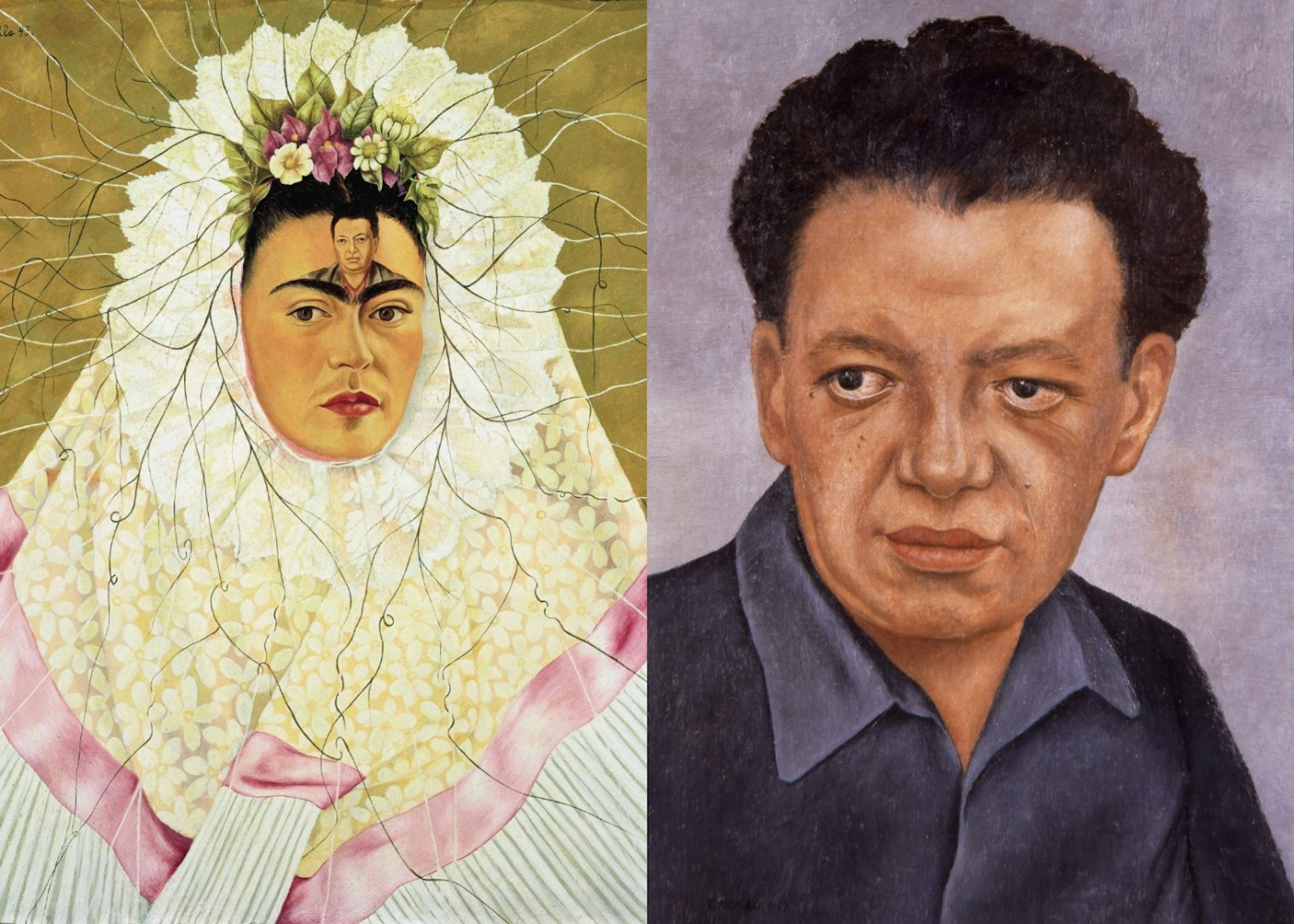

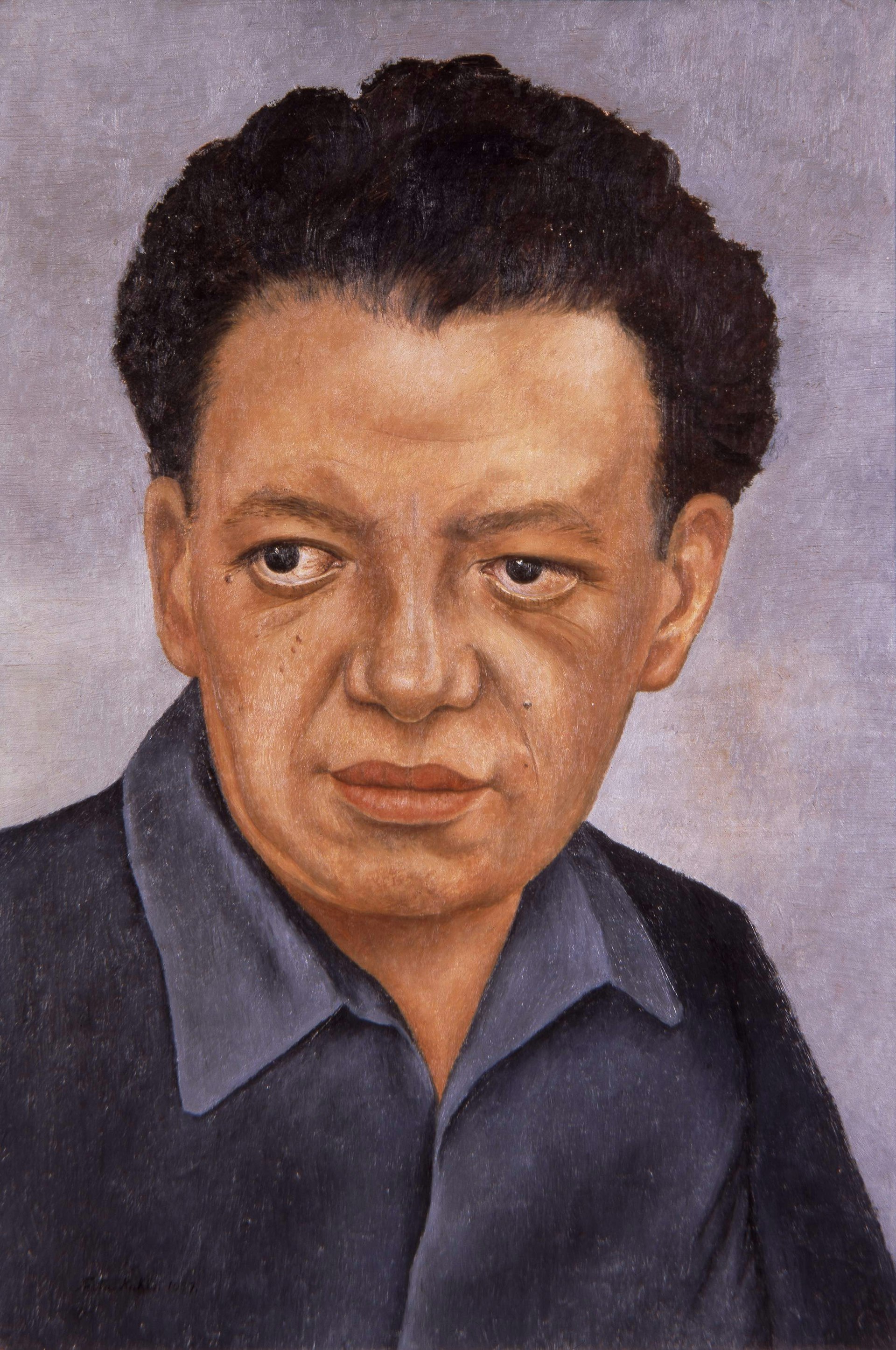

Diego Rivera, Portrait of Natasha Gelman, 1943

Frida Kahlo, The Bride Who Becomes Frightened When She Sees Life Opened, 1943

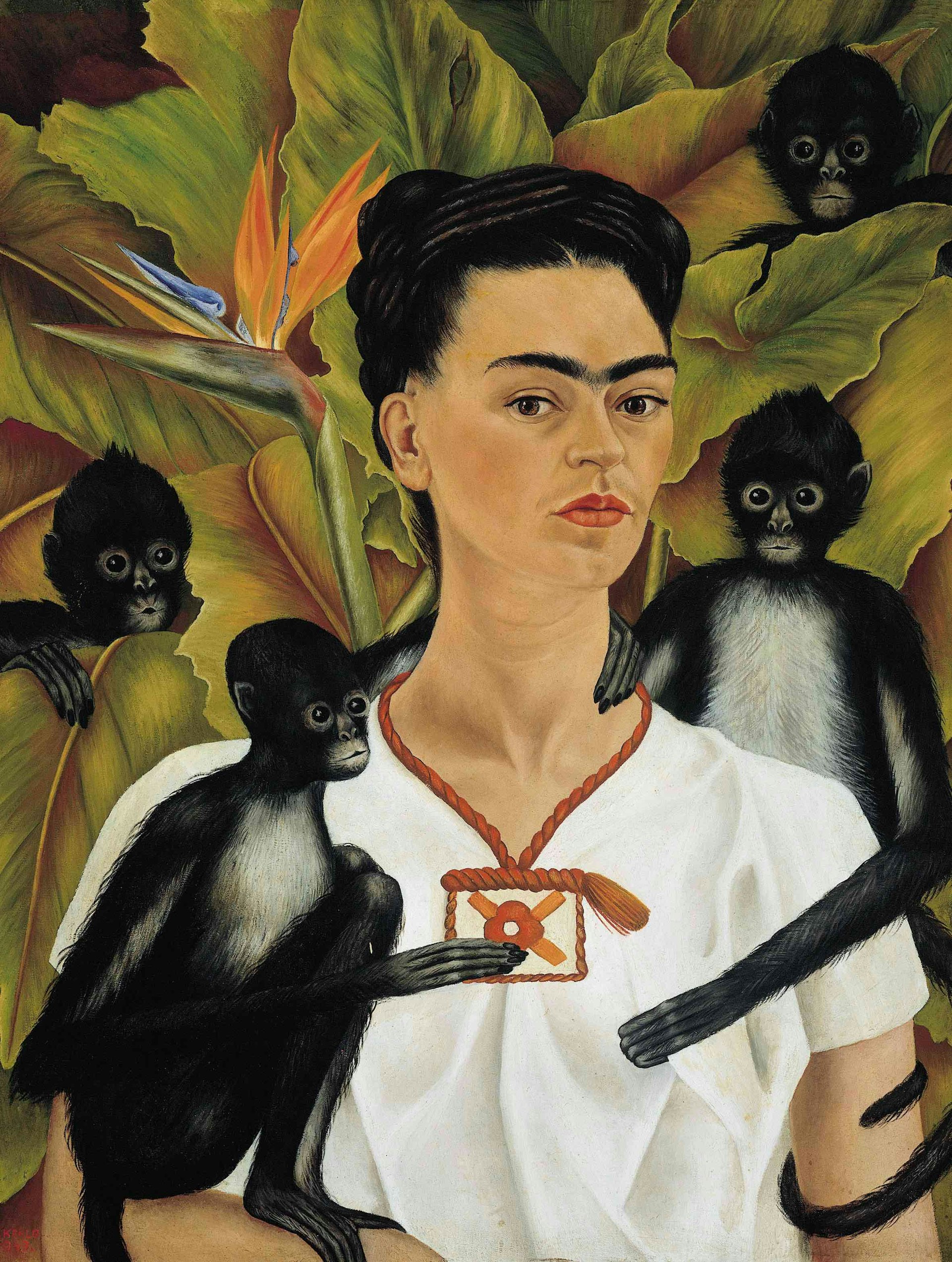

Kahlo asserted “the personal is political” decades before the phrase came into vogue. “Her life was her art; you can’t know one without knowing the other,” Dasal says. “As her joy, pain, and understanding of self were her subject matter, she clearly formed works that allowed her to cope with her relationship’s difficulties.”

Rivera, on the other hand, maintained a more conventional approach to making art. Trained in Europe, he returned home and abandoned Western aesthetics and ideology in favour of mexicanidad. Rivera adopted the distinctly Mexican character that encompasses national history, traditions, culture, and community in the aftermath of the 1910–20 Mexican Revolution.

In the wake of independence, the government set out to rebuild the country and redefine its national identity. Visual artists took up the call, creating a distinctive Mexican modernist aesthetic realised in Lola Álvarez Bravo’s photographs of indigenous cultures, Carlos Mérida’s geometric abstractions, Diego Rivera’s propagandistic murals, and Frida Kahlo’s personal, symbol-filled paintings.

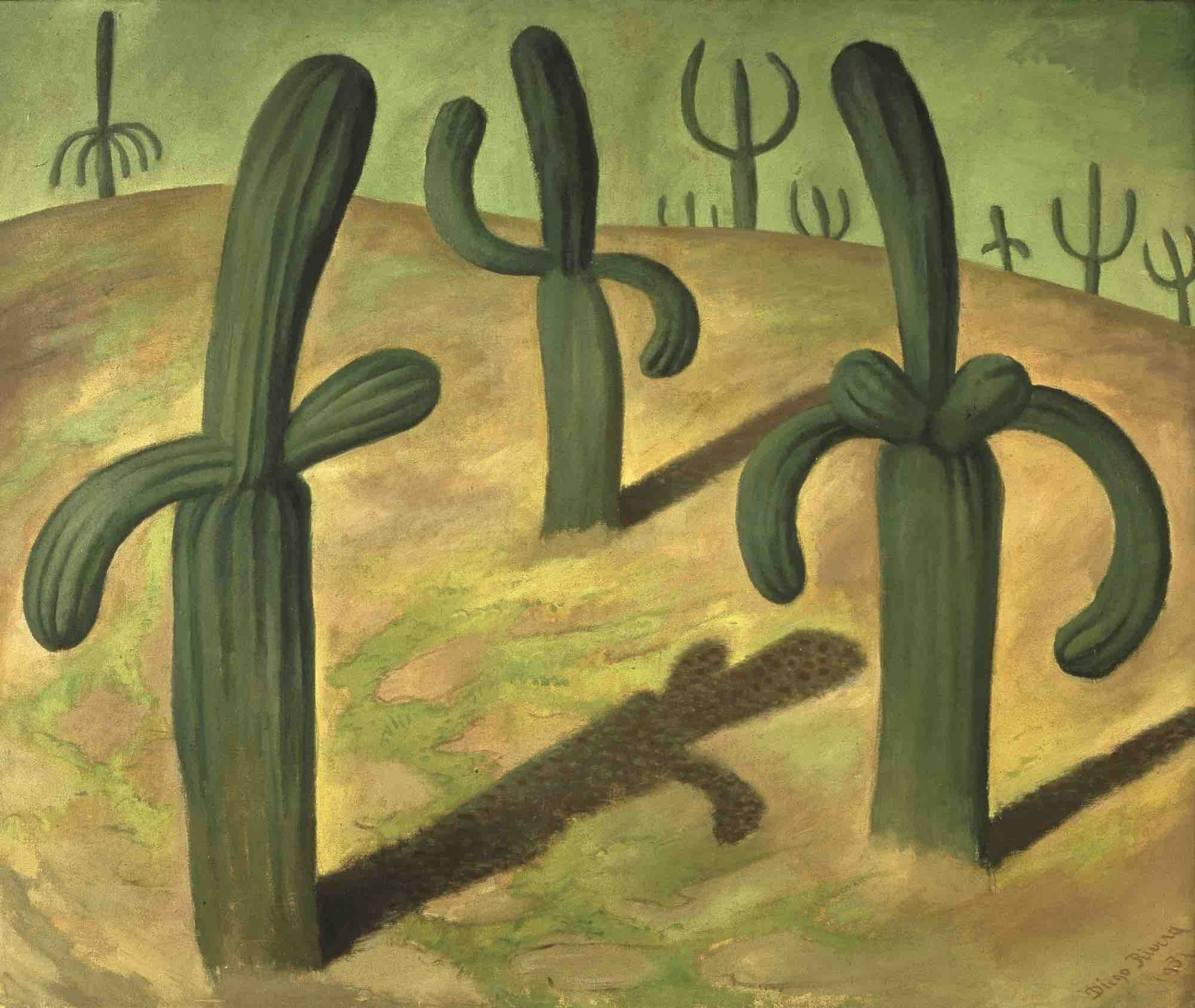

“Mexican Modernism itself is one of the most exciting periods in art, and the post-Revolution period is so fruitful,” Dasal says. “Symbols are found throughout the artwork of both Kahlo and Rivera that connect them to their country. Suddenly, a common sight like cacti, calla lilies, and rebozo (fringed shawls) are transformed into something bigger and more meaningful. The complexity of their works gave rise to one of the most significant chapters in the history of modern art.”

Diego Rivera, Calla Lily Vendor, 1943

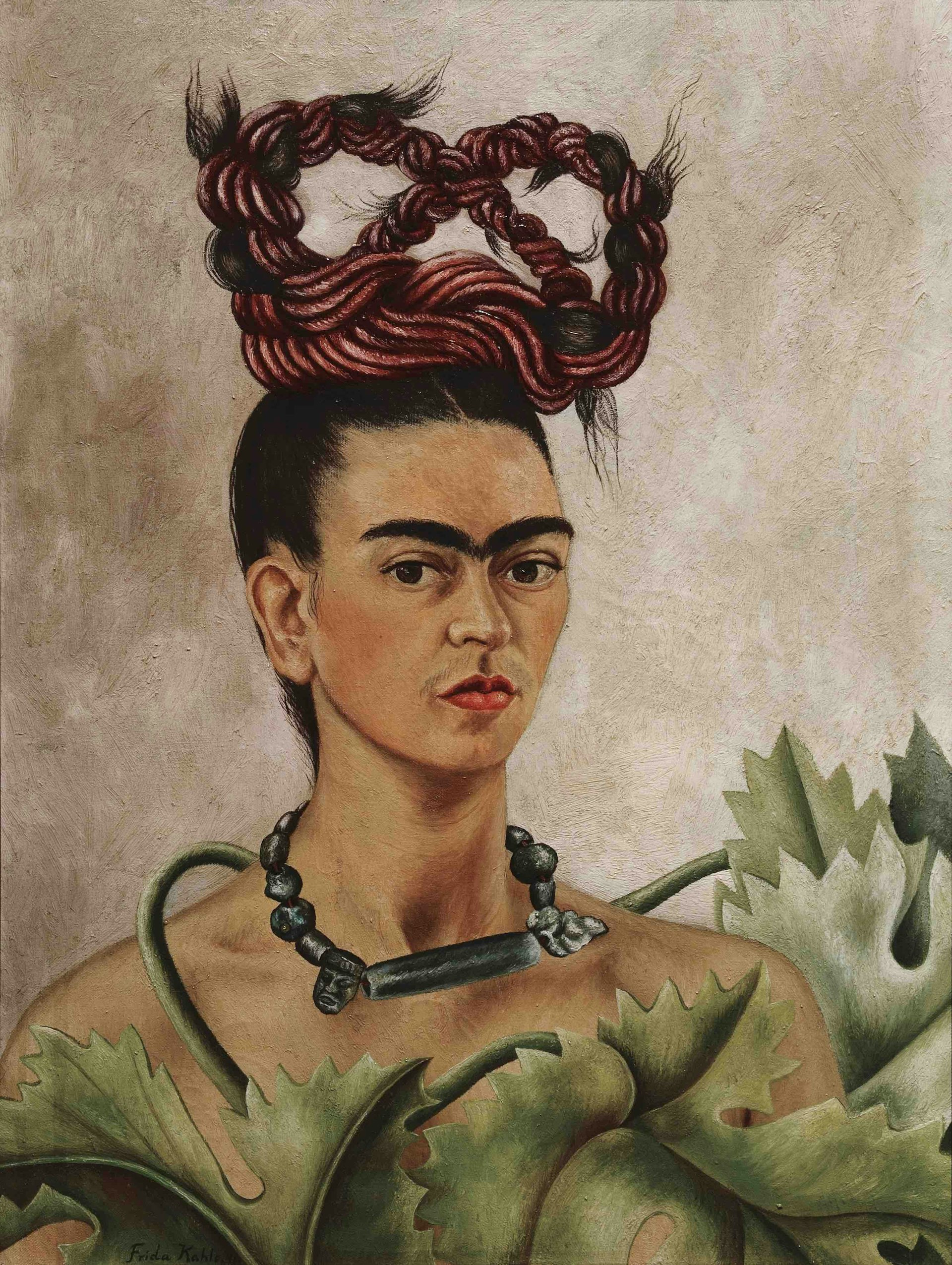

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Braid, 1941

Diego Rivera, Landscape with Cacti, 1931

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkeys, 1943

Frida Kahlo, Diego on My Mind, 1943

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism from the Jaques and Natasha Gelman Collection is on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh from October 25, 2019 through January 19, 2020.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.