Cristina de Middel is a perfect photographer for the post-truth era

- Text by Cristina de Middel, as told to Andrea Kurland

- Photography by Cristina de Middel

The biggest change in my life came from boredom. I was flirting with depression, a midlife crisis, and came to one of the best positions you can have in life: to have nothing left to lose.

It was hard for me to get into the photojournalism world, especially as a woman. I was one of the last staff photographers to get a contract at a newspaper in Spain.

On my holidays I would go to Syria or Bangladesh – anywhere that I could experience the drama of life. But after a decade, I grew tired.

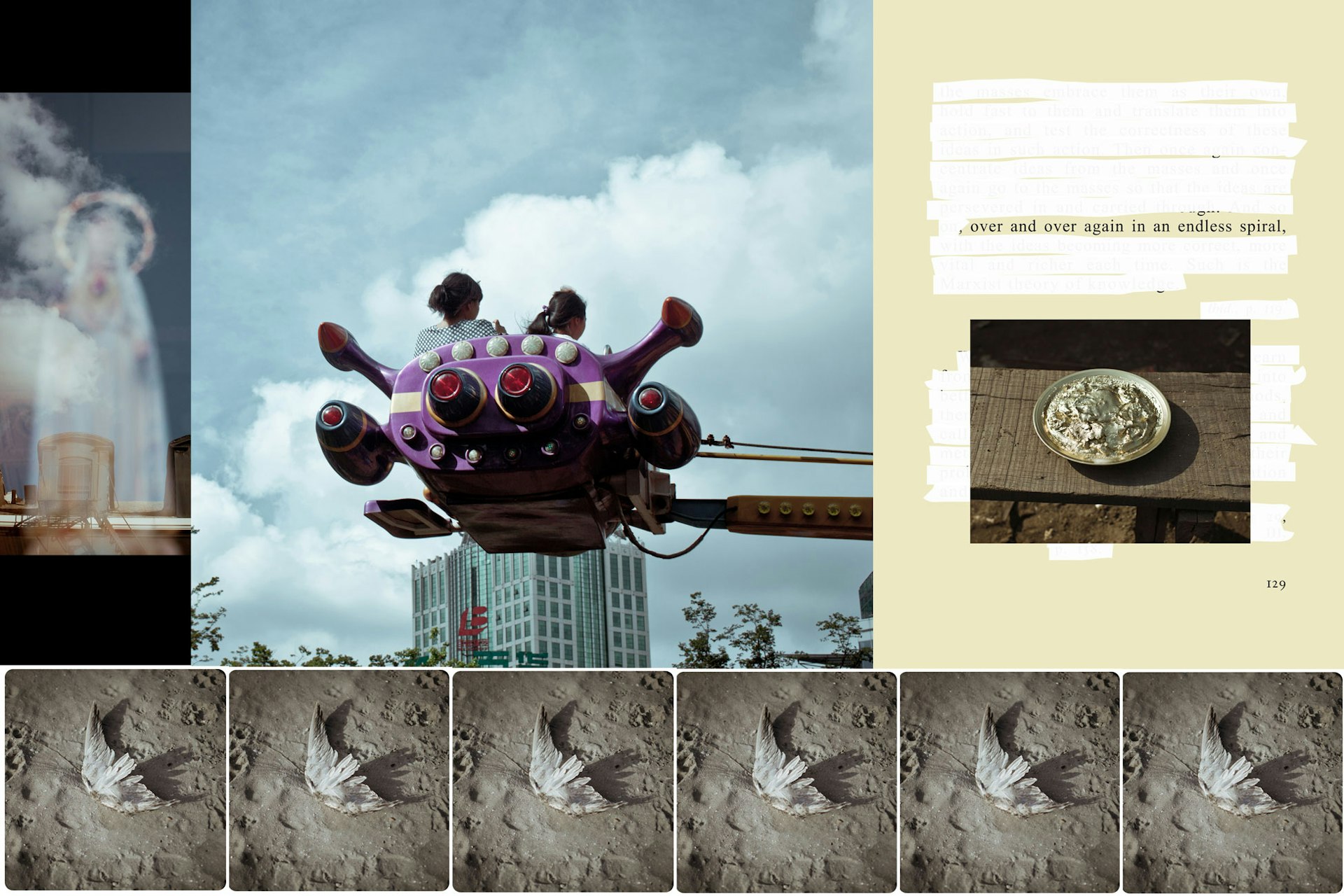

Newspapers are very cyclical; it’s the same thing over and over again. I wasn’t satisfied with how the world was being presented to me: simplifying and reinforcing stereotypes and clichés to direct the opinions of people.

I remember photographing a woman in 2006 at a hospital in Haiti. She asked me why I was taking her photograph and I didn’t want to say, “I don’t know.”

I wanted to live the experience so that I could understand the world and maybe prove that what I’m told in the media is not wrong. But this is a very selfish motivation: it has nothing to do with helping people. As I became aware of that, I grew uncomfortable with this kind of humanitarian photography.

Instead of complaining about it, I decided to create pictures that I’d like to find in the newspaper, stories told the way I would like to consume them. So I quit my job, broke up with my cheating boyfriend, and just totally reset.

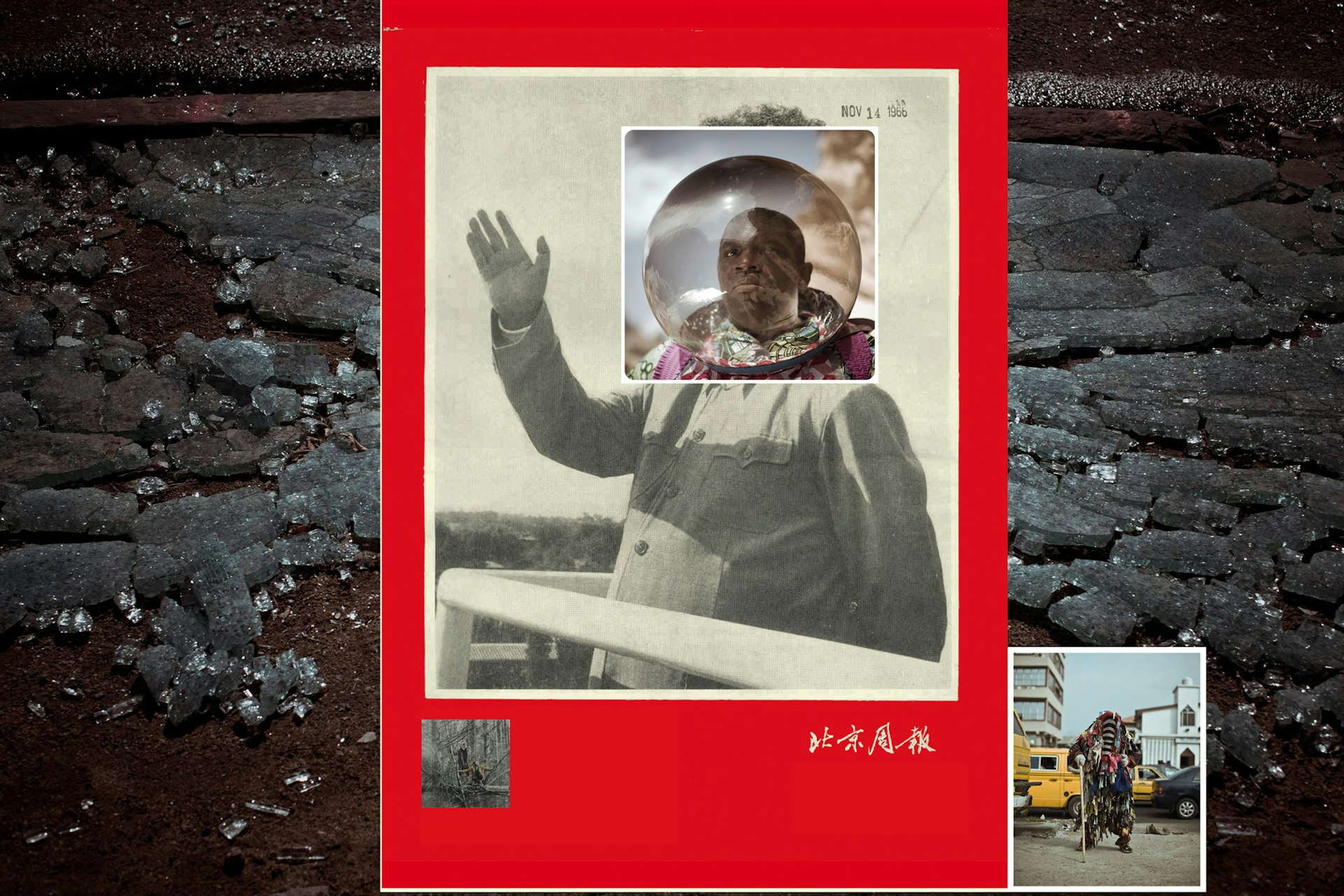

In 2012, while looking for hard-to-believe stories, I found the 1964 Zambian Space Programme – a failed attempt to send Africa’s first astronauts to the moon.

I realised it was way more fun and effective to describe the relationship between Africa and the Western world using this story rather than drought and wars.

It also dawned on me that I have never been a very serious person. The way I communicate is with humour, irony and cynicism. But in newspaper photojournalism, you’re not supposed to give your opinion.

As a photojournalist I was like a hunter, waiting for something interesting to happen. But I started working the other way around.

Nothing that I needed for this series would happen before my eyes if I didn’t manipulate reality, so I started making sketches (I was a comic strip artist in my earlier life) and it came out very naturally.

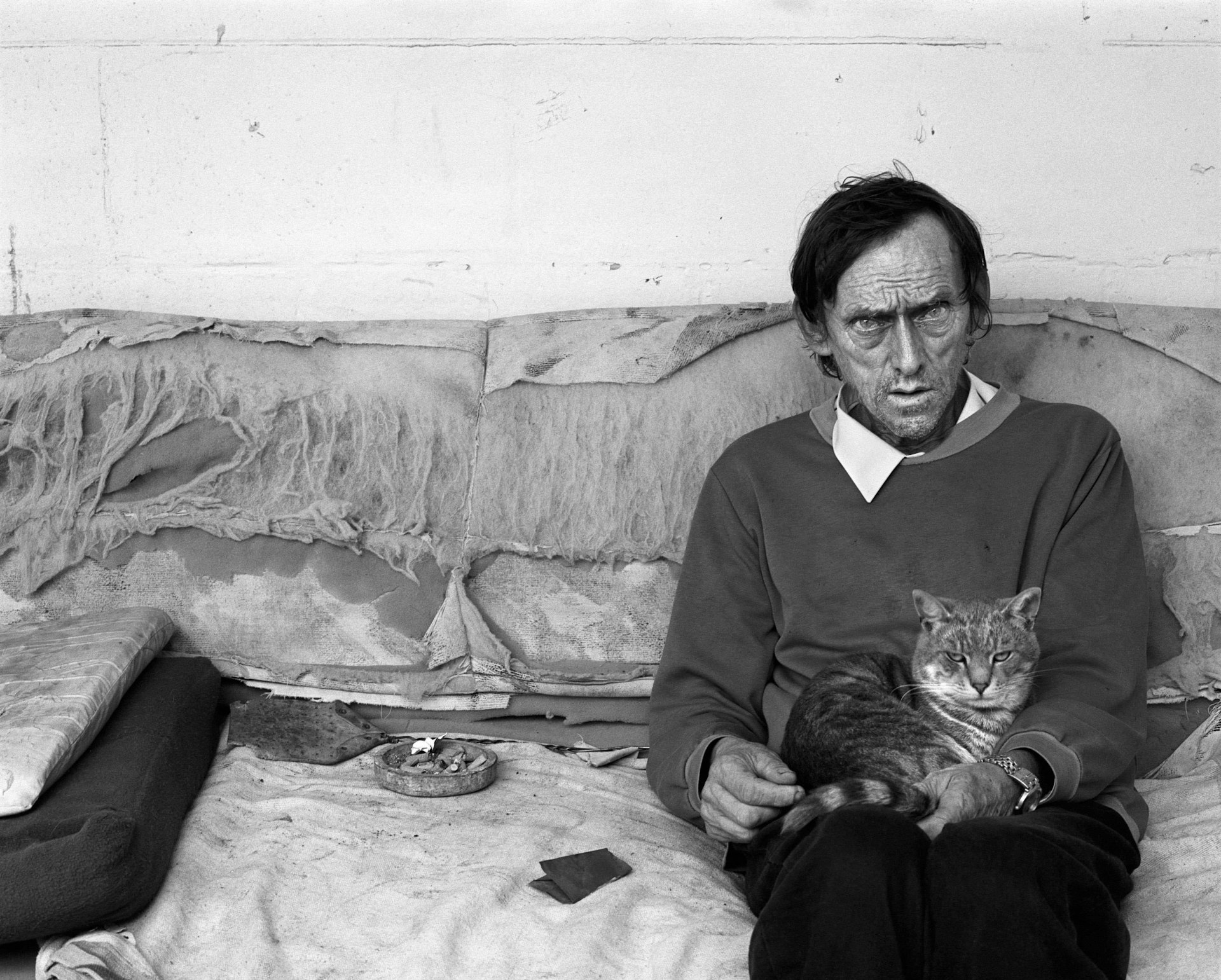

The first portrait I took became the most important, because the man who played the Afronaut helped me position my motivations. He was an engineer in Alicante, my hometown, where I shot the series.

I had no visual reference and was scared he would think it was a joke. But he totally understood what I was trying to say: what’s wrong with Africans trying to go to the moon?

I’ve been asked many times about the representation issue: why is a white woman stating what Africans can do? But actually, it’s the opposite. It’s about misrepresentation. The first time I went to Africa I was like, “Where are the soldiers? Where are the people begging in the streets?”

Go to Dakar and it’s a perfectly functioning city. Africa is without a doubt the most misrepresented continent. It’s had a terrible marketing campaign, thanks in part to the media.

One of the best things about The Afronauts was realising people needed stories like this. People are ready to dream; we’re tired of the same drama. They needed to understand Africa in a different way and I don’t take credit for that – it’s not me who tried to go to the moon.

Documentary should be more about presenting questions and opening debates than stating the specifics of a situation. If there’s nothing I can do then just explain it to me in a different way; don’t make me feel guilty.

After The Afronauts, people advised me to slow down. I had 60-70 exhibitions in a year and was told I was too prolific. So in 2015, I put together my own retrospective as a joke. I based it on quantity not quality, producing 450 prints combining all my projects, and called it Muchismo. It questioned the ubiquity of images.

In photojournalism, you want to reach as many people as possible, but in the art world you’re advised to put out limited-edition prints.

I don’t feel like an outsider in either photojournalism or art. I have one foot here and one foot there, and I’m comfortable. My thing is to make documents of things that don’t exist and to blur credibility of things that really existed.

This article appears in Huck 62 – The Documentary Photography Special V. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Find out more about Cristina de Middel.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.