The story of Stanley Kubrick’s go-to problem-solver

- Text by Cian Traynor

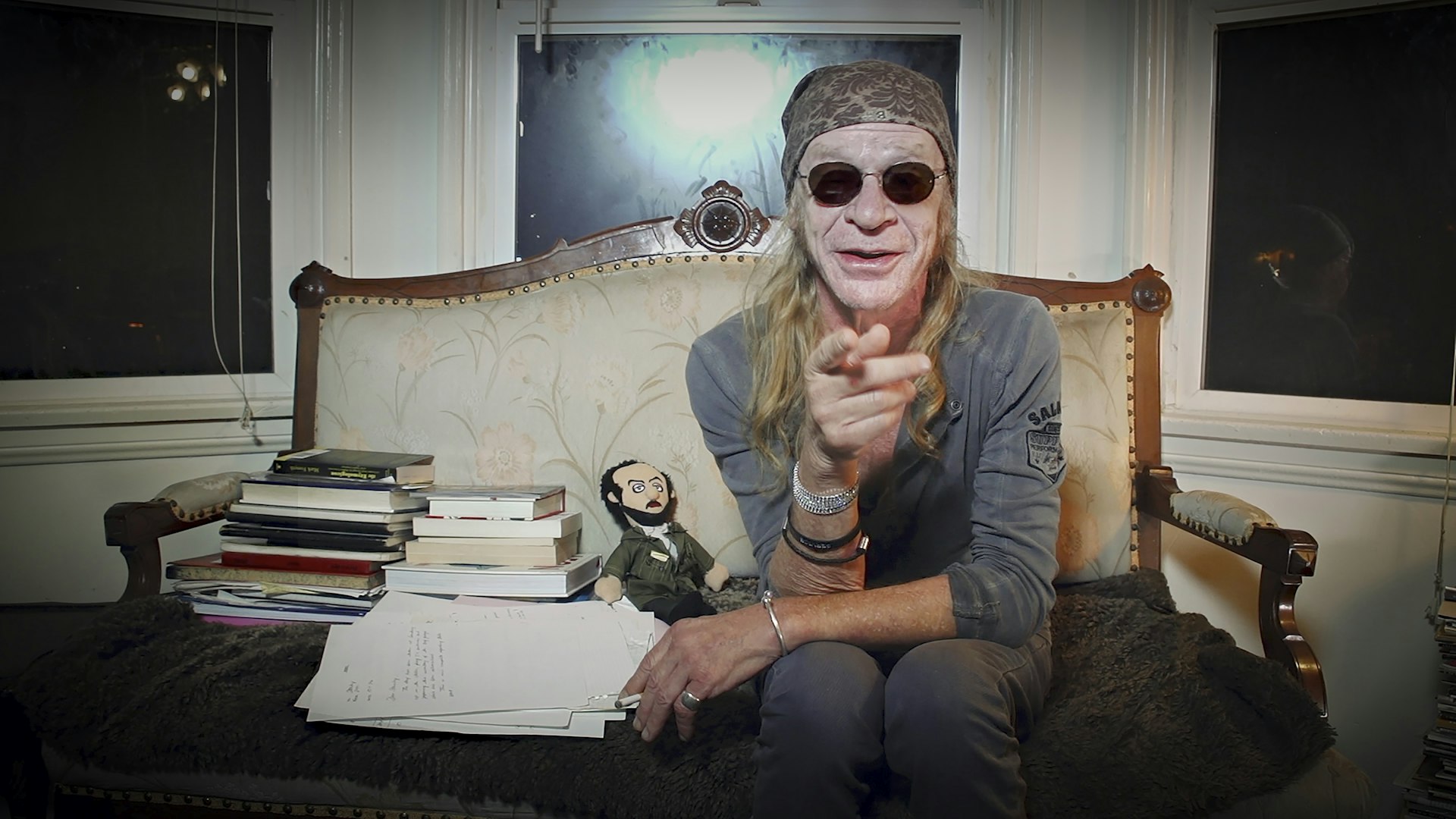

For decades, Leon Vitali has proved instrumental in bringing Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic vision to life. But it also nearly killed him.

It started when, after starring in the director’s 1975 period masterpiece Barry Lyndon, the actor made a decision that took him from the top of the credits to the bottom.

Having absorbed Kubrick’s filmmaking process up-close, Vitali was determined to experience that magic on a much deeper level.

That meant giving up a promising acting career, at the age of 27, to serve as Kubrick’s right-hand man – a shapeshifting role that would encompass casting director, costume designer, acting coach, location scout, personal assistant, foley man, sounding board and all-round problem solver.

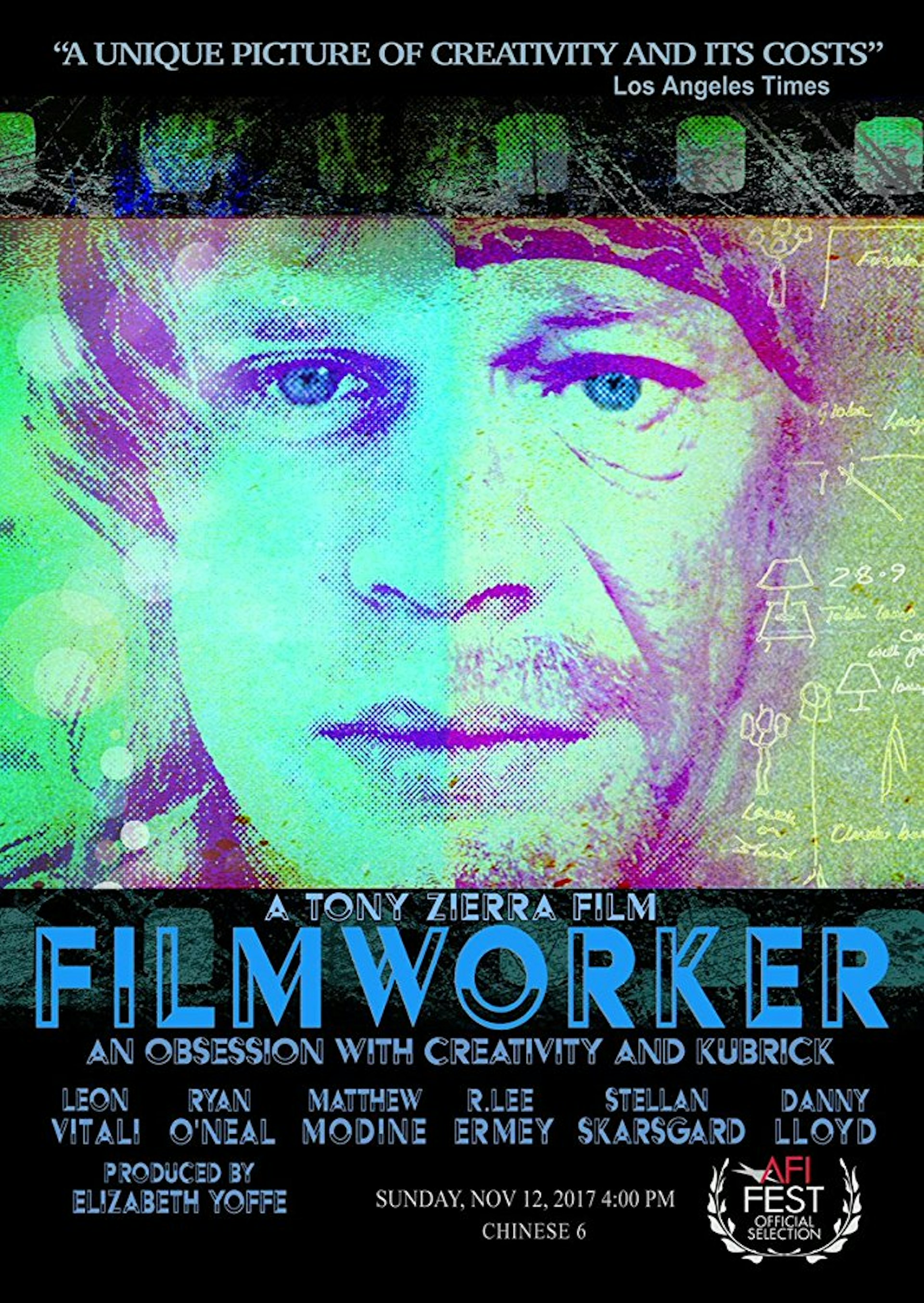

Vitali convinced Kubrick to take a chance on R. Lee Ermey as the drill instructor in Full Metal Jacket; he cast Danny and the haunting twins in The Shining, and played the red-cloaked figure in Eyes Wide Shut.

But in the background, he also worked on everything from translations and marketing campaigns to even looking after the director’s pets when required.

Filmworker, a new documentary about Vitali’s life, offers a remarkable look at behind-the-scenes filmmaking. It’s a story of obsessive drive and focus, of getting the job done no matter what challenge is thrown at you.

That intensive workrate never quite diminished. In the six months after Kubrick’s death in March 1999, Vitali explains, his focus was fixed on delivering the final release as faithfully as possible.

“It was only when we finished that process that I really understood what had happened – that it wasn’t there any more, you know?” says the 69-year-old, who grew up in England and now lives in Venice Beach, Los Angeles.

Asked if that forced him to recalibrate as a person, to take some time for his own wellbeing, Vitali simply shrugs the idea away. There was too much to do.

“Believe me, all those years of intensity continued in other forms: restoring all his old older films for territories where they had never been released before. Then all the translation work, approving the timing of subtitles, bringing the sound into the world of 5.1 stereo and beyond – that continues to this day.

“It’s all a particular and necessary job, which nobody in the world watching movies ever thinks about.”

I understand the sense of fulfilment that comes from being part of something much bigger than you. But what kept you going through all the smaller, thankless tasks that are the opposite of glamorous?

It’s all part of the end product. Everything is a detail inside a bigger brief. Those little jobs are just to keep the decks clear. Sometimes you have bad days. It can throw everything up in the air and land you in chaos. But you just remind yourself that this is what you have to do in order to get to the next point, towards a greater goal.

All this careful work went into every single version of Stanley’s films, and that’s why he celebrated all over the world in the way he is. It was that attention to detail which makes such a difference.

In the film, there’s a scene where your peers are talking about you leaving the acting profession and what you gave up. Did it ever feel, to you, like you’d made a sacrifice?

No, and and I’ll tell you why. When I decided I wanted to be an actor and go to drama school, part of that was the joy and the love of it. Everybody has that initial notion about acting: ‘You can just learn some lines, go on stage and pretend. How glamorous and fulfilling.’

The fact of the matter is, of course, that it isn’t that way. Being classically trained was extremely tough; it involves studying every kind of theatre and technique. But when you go out into the profession you are really challenged because, somehow, you’ve got to be more than good.

You’ve also got to be very fortunate, like I was. But through a quirky set of circumstances, I got to see what went into the actual making of a movie – not just by the directors or producers, but by all the people below the line who pull the whole thing together.

I thought, ‘This is what I want to do.’ And there’s always a bit of a price to pay when you do something you love…

As an actor, I could rehearse for weeks on a project like a stage play at the Royal Court, where you might only do two performances and get paid five quid. And that certainly wouldn’t pay the rent. [laughs]

But if you go around thinking it’s a sacrifice all the time, I suggest you find another job – because it’s going to be that way for a lot of your life. Either you love it and don’t really think about it that way, or you’re just going to be a miserable grouch who maybe doesn’t work all that often.

Where do you think your work ethic came from?

Well, it’s interesting because I really do not believe in organised religion, but there are certain lessons in every philosophy that you end up carrying with you.

I was raised a Catholic and the part I would say had the most influence on me was, ‘If you say you’re going to do something, you do it – and you do it to the best of your ability.’ You don’t set out to do any harm. You’re there to try and help. I don’t think the Catholic Church has always followed its own teaching, which is one reason why I don’t have anything to do with it anymore, but the ethos is still there because it’s hammered into you.

My father was a staunch Catholic and we were caretakers in a school where he was a teacher. When he died, we were able to continue living there and, in return, we continued to be the caretakers. So from eight years old, I had a job after school every day. We didn’t have any money but we weren’t unhappy.

My mom was a nurse all her life and there were times when she just absolutely collapsed under the weight of the responsibility… and had to sort of nurture her way back into being able to do the job – and that the thing, isn’t it? It’s a vocation, not a job.

But all those things – the work ethic, what happens in your life – you learn as you go along and I’m a constant student. I learn things everyday because situations arise which require different ways of handling them or thinking about them. So it’s something which never really leaves you.

Looking back, what quality of life do you think you and Stanley had away from movie sets? Was it just onto the next thing, onto the next thing?

Oh, it was pretty much constant, constant, constant work… That’s just where we were at. I became perfectly aware of the demands put on you in those situations.

But I volunteered for it, for want of a better word, simply because I loved it. It’s a huge canvas. There were some wonderful, magical moments of achievement which I think anyone would have given anything to feel.

Of course, there were also stressful moments where you just think, ‘Oh my God, this is the worst thing that can happen’ and you don’t know if you’re going to get it done, but you have to keep going until you do – or at least find a way around the problem.

But I don’t look at a painter or a writer and think, ‘Oh, poor person, that must have been hard.’ I read their books or look at their pictures or watch their movies or whatever it is and realise, ‘A lot of stuff has gone into this.’

And you appreciate it for that as much as anything else. Whether it resonates with you emotionally is another question altogether. It’s a very complex thing, you know. There aren’t any rules; there’s no guide book. It’s not like you’re in a procedural situation; most of the time you’re dealing with things as they happen and it’s hugely collaborative.

No one appreciated that more than Stanley. People talk about him being isolationist or a control freak and of course, at times, you have to isolate yourself, you have to take control because you don’t need the distractions that can sometimes play upon your life.

But I will say that Stanley was completely and utterly open to free-wheeling. He would always say, ‘Well, what do you think? And what do you think?’ That openness to ideas and suggestions made it quite delightful. You knew you were part of a creative team, rather than just a cog in a wheel.

In the film, we see your family talk about the impact of your dedication. How did that make you feel?

Well, I mean… interesting to hear! Absolutely. [laughs] As a family we can go for years without seeing each other but as soon as we’re in the same room, it’s like we were talking yesterday. That’s a measure of our relationship. Of course, we’ve all had periods where we kind of worried about each other. But we don’t live in each other’s pockets either, put it that way.

But… what did it make me feel? I don’t know, to be honest. I suppose if I had any conflict about the intensity of my profession, really, it would be my children and my relationships. It led to divorces and things like that. Those were my more immediate worries. My whole family has always been sort of geared towards, ‘Well, life is what it is and you try to deal with it and cope with it, but it needn’t stop you from following your deepest interests as a way to live.’

Do you think Stanley felt fulfilled or was he constantly constantly battling frustrations and insecurities?

Always [battling], like everybody else. [laughs] I mean if you want to make a movie, think about the number of people who have to be on board and focused on following a particular path – one where simplicity is the hardest thing to achieve – and yet you’ve got to steer the whole thing down this narrow road… and all for a piece of 35mm celluloid. It’s astonishing, when you think about it.

What do you think Stanley’s insecurities were?

I think the same as anyone who pursues an ‘artistic’ endeavor, when you’re trying to interpret how you see life in a particular way. It may not work, it may fail, you may be stopped from doing something you really believe in. And you can’t be afraid of that.

It’s a very delicate balance: being sure that something’s working and then being able to go through a period where there’s frustration, where things aren’t going your way and you feel like giving up.

I think of people like Terry Gilliam. He’s had lots of wonderful success, but also had to fight battles against what seems to be an army of corporate people who don’t really have anything mentally in common with his world or how he sees it. Having projects cancelled can be heartbreaking.

With Stanley, we had three or four other projects where we had to abandon ship – and the letting go is extremely difficult for a lot of people, whatever area they might work in. But he had a very open mind, more so than most people I’ve ever met.

Stanley faced some really hostile reactions to his movies. I mean, deep in your soul, you want everybody to say, ‘Yes!!’ But, you know, he never made his films telling people what to think about them. You had to make up your own mind. And Stanley never really subscribed to the idea of living happily ever after either, which is a residue of fairytales and remains the basis of most storytelling, even today. So all that can leave you open to a huge field of critical feedback, whether it’s positive or negative.

But to answer our question, I remember when somebody asked him ‘How are you getting on?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I’m still fooling them… and thank God for that.’ [laughs]

Was there anything in your last conversation with Stanley before he died that stuck with you?

It was a Saturday afternoon and I had sneaked out for an hour to do some shopping. [laughs] That was the only way you could do it! So I was in a supermarket car park when he rang to talk about a new task I’d been given: running through the movie [Eyes Wide Shut] as it was cut in order to prepare the screenplay for publication.

But we were on the phone for almost two hours because, with Stanley, you could suddenly start talking about anything. That’s how our relationship sort of budded, I suppose, when I first met him as an actor. I’d sit next to him when when we were shooting a scene, when they were getting a new lighting setup ready. He’d sit with you – and he did this with a lot of people – and we would just talk about politics, about football, about great actors or movies that we’d seen.

We didn’t always like the same things but it meant we had a far-reaching discussion. That day, we had one of those wonderful conversations where we talked about exactly how nuanced we wanted this to be and the depth it needed, so that you could read and follow along even if you’d never seen the film.

On the Sunday, when I was about to come in, I got a phone call saying, ‘Could you delay it? There’s something going on here.’ I said, ‘Sure, of course.’ Then I realised that I’d never had a phone call like that. If things were happening, I was generally part of it.

So I went into work – I only lived 10 minutes from ‘headquarters’ – and I saw an ambulance outside the front door, along with two or three police cars. Then it clicked that something terrible that happened – and it had.

The conversation wasn’t somehow different because he knew he was dying – it was a massive heart attack that took him. But it reflected a side to the relationship that we always had – gentle and warm – and it was the kind of wonderful exchange that we could have had every day. That’s how he was sometimes. It wasn’t all shouting and screaming by any means.

Is there a piece of advice, based on something that you’ve you’ve gleaned from from your career, that you find yourself sharing again and again?

Absolutely. The two key words I always want people to remember are curiosity and perseverance. Those are the things you need to feel fulfilled, whether you become a star of your particular profession or not.

From time to time I’ve coached young actors trying to find a way into the profession, which I also did on most of Stanley’s productions and what have you. Of course, the dropout rate is ginormous.

When I was an actor, we had three television channels in England and you couldn’t get a job in film or in the West End unless you’d done 40 weeks of paid professional work. There was like a 90 per cent unemployment rate on any given day. Now, there are thousands of outlets and yet you’ve still got the same situation across the board. It’s like when people say, ‘Oh there’s so much traffic, let’s build a freeway.’ Then they build a freeway and you’re not moving on it because there’s so much more traffic.

If you’re gonna stay with it, you’ve not only got to really want it – you have to understand the reason why you’re in it at all. As a child, I was so curious… which often means being a naughty boy who’s always in trouble. But now that I am where I am, I can see that being naughty was the least of it.

That curiosity meant that I found out lots of things I might not have ever found about, especially when it comes to the nature of people. It’s part of the rich pattern of life, I guess you could say. And it never stops. If you stay curious, it never stops.

Filmworker is out on digital and DVD.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.