Kiki: The wild dance movement formed out of radical resistance

- Text by Kieran Yates

- Photography by Krisanne Johnson

At a 24-hour restaurant in Manhattan favoured for its people watching, Gia Love is drawing glances from other diners.

Wearing black jeans and a tank top, the tall 25-year-old cuts a distinct figure: flicking and smoothing a hip-length brown weave as she describes her first experience of a ball.

“I felt like it was a space where I could be myself,” she says of the Hetrick Martin Institute, a non-profit dedicated to serving the needs of LGBT youth. “And there’s not many spaces where people like me, a trans woman of colour, can be ourselves.”

Gia and her four siblings were raised in the Bronx by a single mother who did the best she could with the little they had. Although her family struggled to accept Gia’s gender presentation when she was younger, she was determined to be herself.

She features in new documentary Kiki – a colloquial term for ‘just having fun’ – which explores a ballroom subculture of the same name. If it wasn’t for ballroom, Gia says, she would have never known what it’s like to be accepted for her true self.

For those unfamiliar, ballroom refers to an extension of the New York drag circuit which first emerged during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

But as much as these carnivalesque pageants celebrated sexual and gender nonconformity – championing dance moves and fashion styles that defied the grey categories of the era – they were typically presided over by white men.

By the 1960s, Harlem’s black community developed its own exclusive events where participants would vogue – a stylised dance that was all angular body movements and model-like poses – and ‘walk the ball’ under different themes and categories, from ‘realness’ to ‘vogue femme’ and beyond.

It all took root at locations like Rockland Palace, which is revisited in the documentary as an homage to ballroom’s history. The scene exploded with its own self-styled energy but it would be another 30 years before the world cottoned on.

In 1990, Madonna catapulted ballroom’s moves into the global spotlight with her hit single ‘Vogue’. And in 1991, cult documentary Paris is Burning dug at the stories and struggles at the movement’s roots. But the general consensus in the community is that the scene has evolved.

Paris is Burning may have been the mainstream’s first insight into this world but Kiki takes us straight to the present. “I didn’t feel like [Paris is Burning] represented the trans experience,” says Gia.

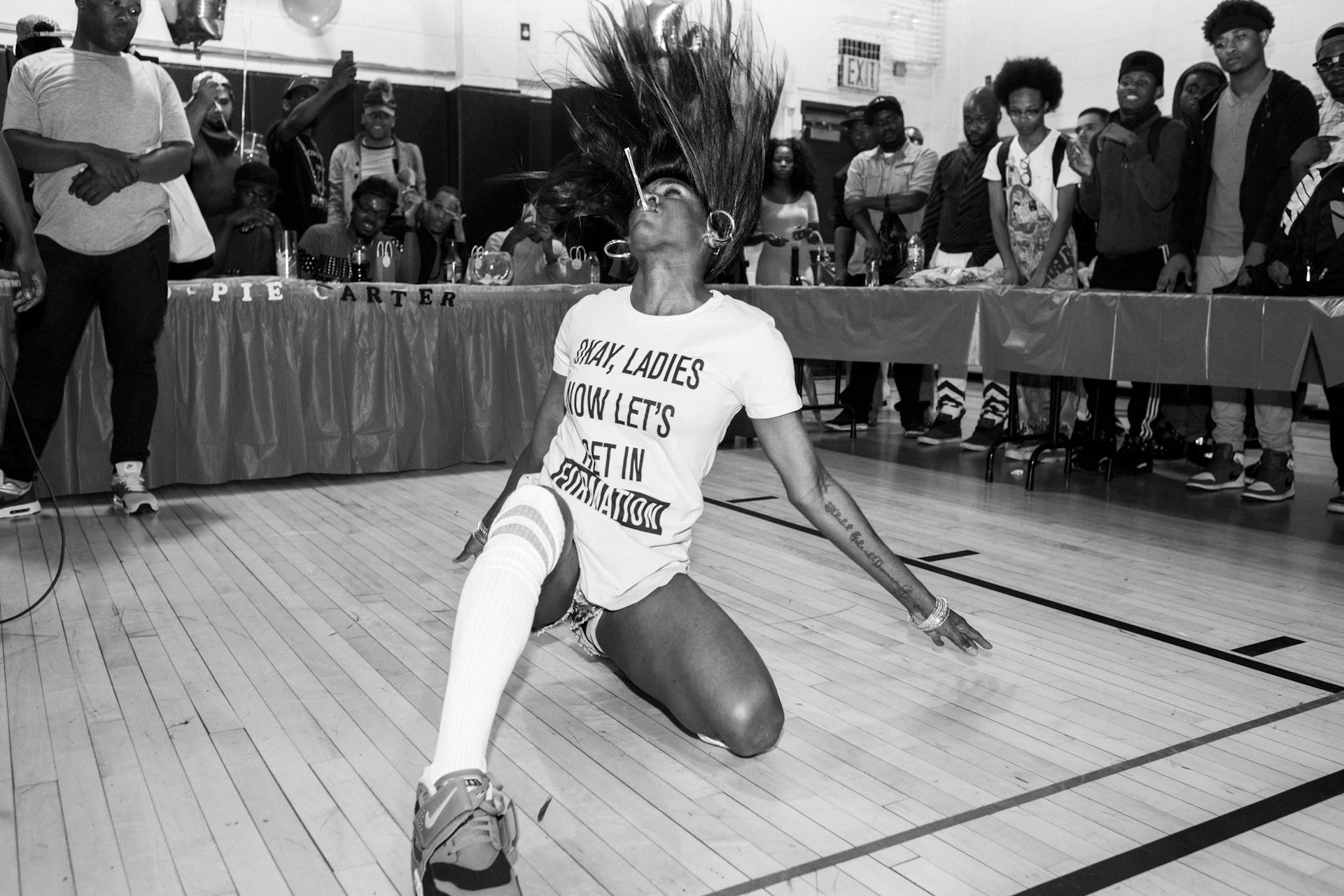

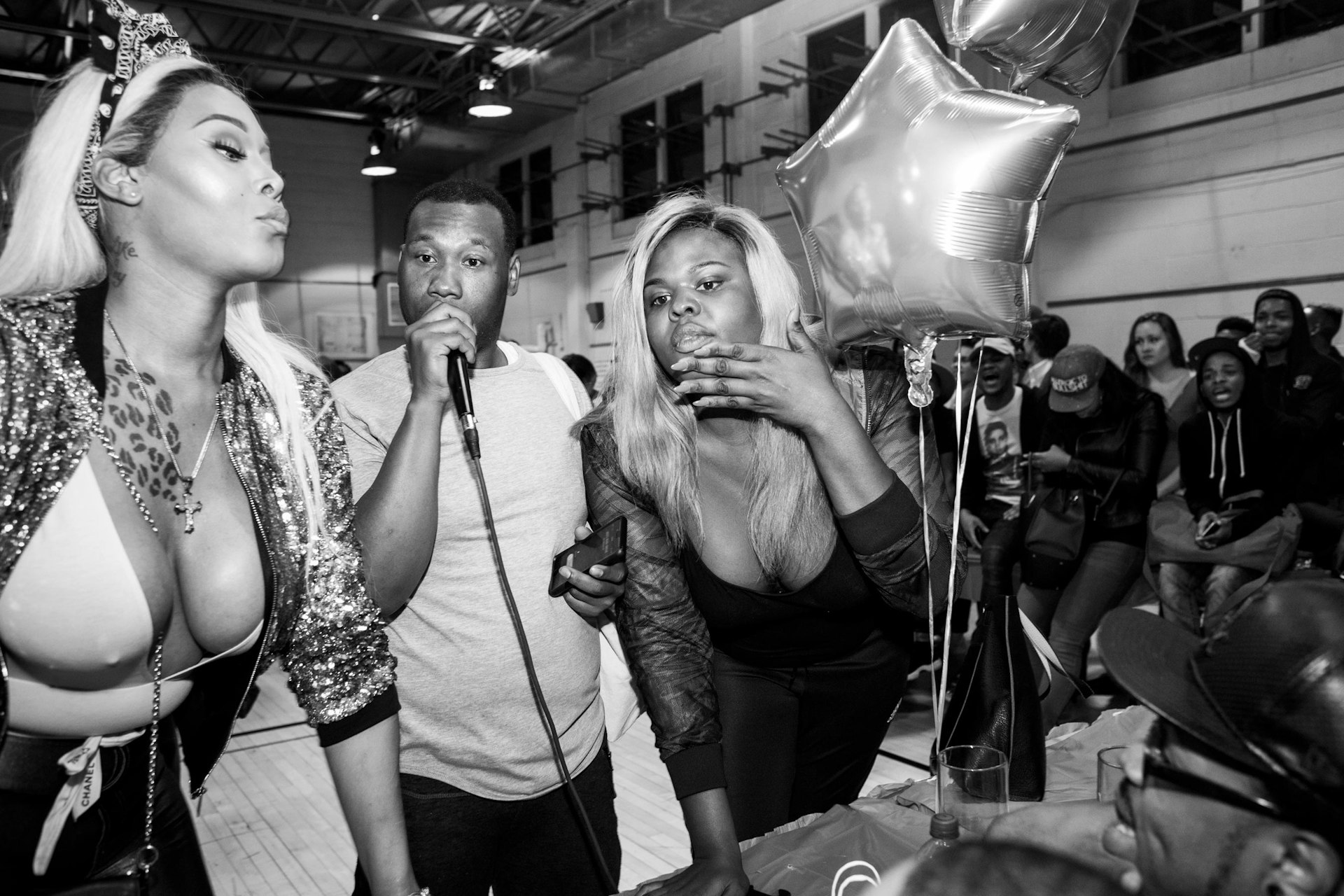

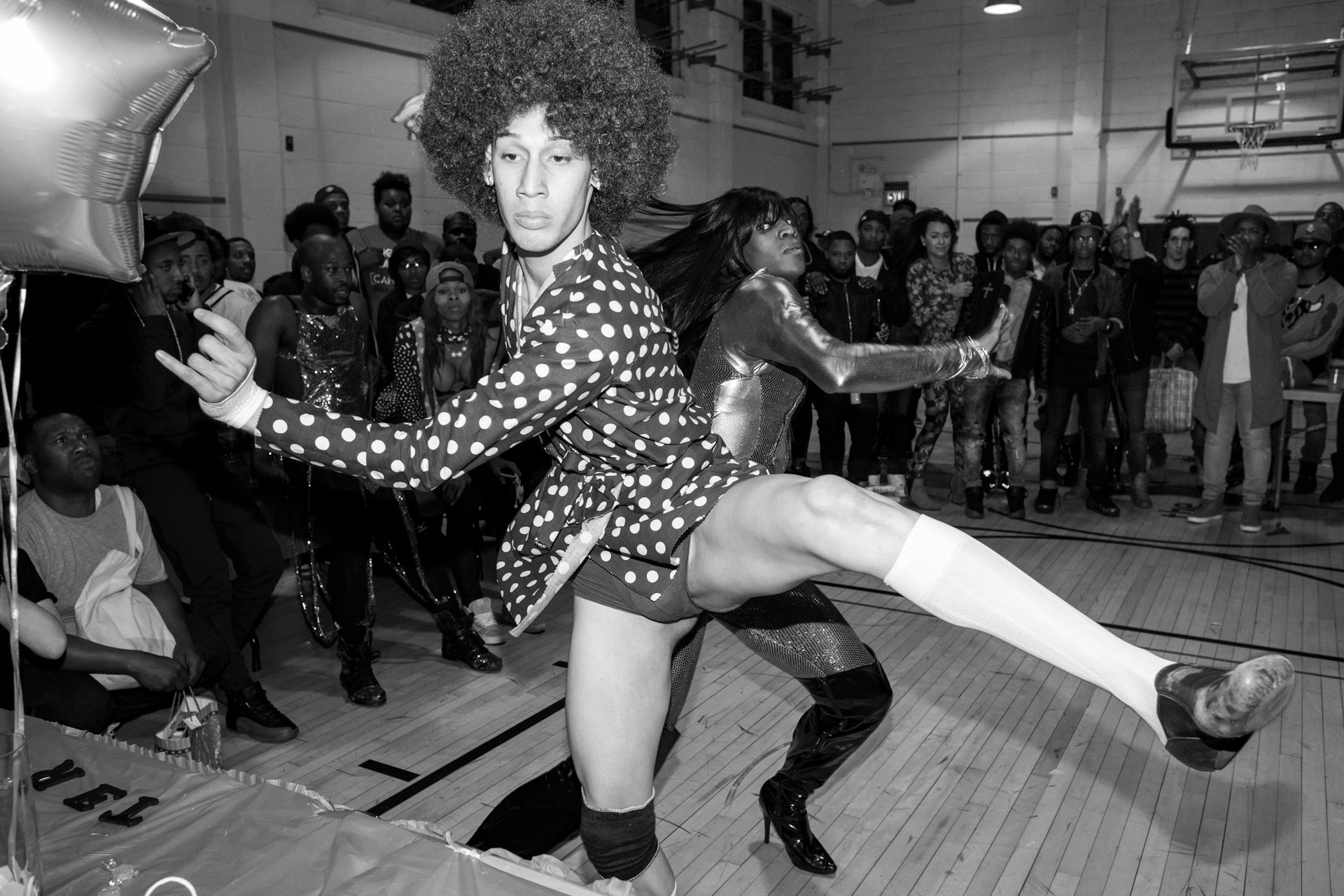

Gia Love (right) at a Kiki ball at the Rutgers Community Center in Manhattan, NY.

“Plus, things are different now. On Facebook, for example, I have a group where we talk about everything to do with race and transphobia and politics.

Even Instagram can be affirming. I think this generation are more open-minded and forward-thinking. Not that the previous generation aren’t, but I feel like we are more active and are having radical, progressive conversations about our situation.”

That outlook is what sparked Kiki, the documentary. Four years ago, Twiggy Pucci Garçon – a lynchpin of the Kiki scene – realised that the time had come to represent LGBT black and non-white identity in contemporary America with nuance.

“I was talking to my friend Chi Chi [Mizrahi] about why there hasn’t been another doc about ballroom other than Paris is Burning and How Do I Look [2006],” says Twiggy.

The 26-year-old, who’s originally from Virginia, co-wrote the film with Swedish director Sara Jordenö in order to illuminate a way of life that goes unseen. While still part of the wider ballroom community, Kiki is a youth-driven offshoot pushing for social change.

“Kiki is more than entertainment,” says Twiggy. “It has a history formed out of radical resistance to homophobia, transphobia and racism. It was created out of struggle.”

“The Kiki scene is revolutionising vogue,” says Billy Green, programme director at SCAN NY G.L.A.S.S., one of many non-profits working within the Kiki community to provide housing referrals, education and social support. “They’re getting out there and believing in their talent. They’re giving a voice and authenticity to a lot of narratives that need to be told.”

Homelessness in New York City reached a state of crisis during the 1980s. A combination of economic cutbacks, unemployment and a lack of resources to deal with the HIV epidemic forced people onto the streets in unprecedented numbers.

At its peak, demand for space at the city’s homeless shelters doubled to more than 28,000 people on any given night.

Yet ballroom culture boomed, developing its own infrastructure and spreading to other cities. Participants began banding together in alliances known as ‘houses’ under the guidance of a ‘house mother’ or team leader, with each family boasting its own distinct identity and culture.

The House of Swisher Sweets practise at the SCAN Johnson Cornerstone Community Center in East Harlem. The SCAN NY G.L.A.S.S. (Gay, Lesbian and Straight

Supporters) program provides a safe space in Upper Manhattan for LGBT youth of colour. Some Kiki Houses use the centre for practice.

These houses formed an underground social network: essential not just for mobilising and organising events but for offering marginalised figures a sense of community.

Today ballroom is international, with parties taking place everywhere from Paris to Tokyo.

The Kiki scene in particular serves as a safe haven where at-risk gay and trans youth (mostly aged between 12 and 24) can become better equipped to deal with life beyond the balls.

Whereas mainstream voguing embraces competition and high-fashion, Kiki also focuses on DIY attitude and social activism.

The Kiki Coalition – an overarching body made up of various outreach services – aims to reclaim public spaces by organising balls everywhere from school gyms and warehouses to clubs and community centres.

The Kiki Coalition – an overarching body made up of various outreach services – aims to reclaim public spaces by organising balls everywhere from school gyms and warehouses to clubs and community centres.

“My favourite theme was ‘intergalactic avant-garde and haute couture’ – all in one look,” says Twiggy of a recent ball. “I spent seven hours in make-up where an artistdid my entire body with prosthetics and stones. The dress took, like, two months to make.”

Twiggy is mother to the House of P.U.C.C.I., a name partly inspired by designer Emilio Pucci but also an acronym for Peers United for Community Causes Initiative.

As a teenager in Virginia, Twiggy volunteered at a community health organisation and followed that pursuit to New York, where – despite being forced to couch-surf while struggling to make ends meet – he became an influential advocate in areas such as sexual health and substance use prevention.

Twiggy now focuses on tackling LGBT youth homelessness through his day job with non-profit organisation the True Colors Fund.

And, as the documentary makes clear, there’s a sharp contrast between the glitz of ballroom and the everyday life of dancers struggling to survive on the streets.

One scene in particular suggests that while same-sex legislation felt like a win for the white gay community, homeless trans women of colour are left fighting a very different battle. Transgender people are being murdered at a historic rate worldwide.

Last year saw a record 22 reported cases in the US and a further 14 this year at the time of writing – almost all of whom are women of colour – though the Human Rights Campaign believes the true number may be far higher.

In June, a gunman opened fire on an LGBT nightclub in Florida, killing 49 people – the deadliest mass shooting in US history.

The statistics tend to leave many in the ballroom community feeling that when it comes to matters of gay rights in the US, non-white LGBT issues go ignored. And there are signs on the horizon that things could get worse.

“Being exposed to Trump is very scary,” says Twiggy. “It makes you realise that oppression is real, racism is real, transphobia is real. I’m concerned that right-wing leadership will be a halt to where we are in the movement. We’re at a phase where we just can’t afford that.”

So how can Kiki make a lasting cultural and social impact beyond the ball?

For the older generation of voguers, it’s crucial that mainstream audiences give ballroom culture the credit it deserves. I hear about performance artist Derek Auguste countless times before I finally meet him at a BBQ joint on West 23rd and 8th Avenue in Manhattan.

Best known under his stage name ‘Jamel Prodigy’, the 32-year-old has achieved the honour of ‘legendary status’ in the voguing scene over the last 15 years.

Derek Auguste strikes a vogue pose on Lexington Avenue in East Harlem, NY.

“Can I just say this…” he says, pointedly. “Voguing is not a trend… You see these brands and artists trying to cash in on vogue? That is what appropriation looks like.

“Yesterday you didn’t see it but today, because Sarah over in the suburbs is doing it, it’s the fab new thing! Now the Hamptons are voguing… while we’ve been voguing on the pier, on our own, for years!”

As a teenager attending dance school in Harlem, Derek often missed out on big roles because of his height (5ft 7in), which affected his confidence. But finding an outlet at balls unlocked his passion for vogue.

He now works as a dance teacher and, over the last two years, has become a frequent collaborator of FKA Twigs – the experimental British dancer, singer and producer – after she approached him for lessons at Vogue Knights, a weekly ballroom event.

In person, he’s charismatic and full of energy, gesticulating enthusiastically over a plate of wings and fried okra.

“Vogue is expression,” he says. “It’s catharsis. It’s taking your energy to a place of beauty and letting all that transphobia and racism and negativity out in the most fab way.”

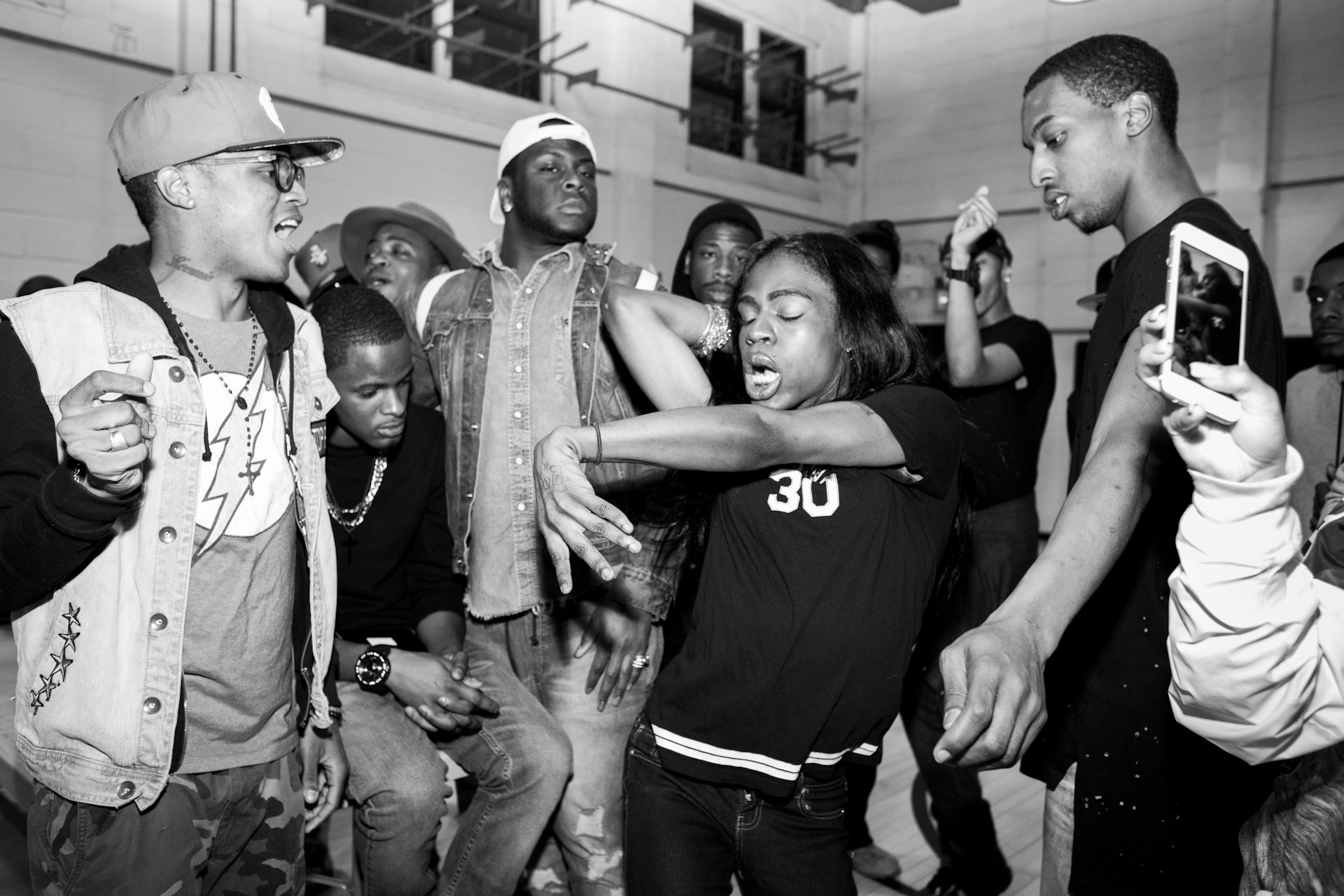

Simply put, vogue is a fluid but ferocious dance based on (roughly speaking) five elements: catwalk, spins, duck walking, dips and hand performance. For figures like Derek – who’s trained in classical, jazz and tap – this is a craft worth investing in.

“Are people going to pay dancers from the community to vogue at their shows? Are they going to allow these kids to make a living from their art?” he says, his joviality cracking into frustration at how the scene has been consumed and portrayed in the past.

“After Paris is Burning, people just thought that these fab young kids were all HIV-positive and had nothing else going on creatively, you know? But it’s like, hello? Some of these people are students and artists and community organisers – yet all you care about is how cute their spins are.”

Derek wants to show the world that black culture is multidimensional. As part of that mission, he’s using vogue culture to establish himself in art spaces “where there’s not a lot of people like us”.

When we meet, he’s recently completed a performance piece at the Tribeca Gallery, throwing paint inside a plexiglass cube while voguing to the beats of DJ Mike Q (‘the crown prince of modern ballroom’) and FKA Twigs.

“Why can’t we push boundaries?” he says. “Why can’t we be stepping out of the clubs and be making art history?”

To reinforce how far the possibilities can be pushed, Derek takes me out that evening to an exhibition afterparty in Harlem for fellow multidisciplinary artist Rashaad Newsome.

Inside, the dance floor is dominated by a circle of voguers trying to outperform each other as commentator Kevin JZ Prodigy sets the pace, shouting ‘Cunt!’ on the beat at double speed.

Arms are outstretched, fingers are pointed and backs are slammed into death-drops.

The soundtrack shifts between rapper Cakes Da Killa (who jumps up on a bench to deliver an impromptu performance), DJ MikeQ, classic ballroom tracks by Byrell the Great as well as chopped and screwed versions of Aaliyah, Beyonce and Missy Elliot.

You can see why superficial readings might miss the urgency, solidarity and jubilance underpinning it all: as an outsider, it’s a euphoric experience to witness.

But when we leave the party in the early hours and make our way to the subway, pointed stares make it clear that voguing in the street can quickly feel like an unwelcome source of tension.

That part of the experience doesn’t seem to have changed. The next day, in Rashaad’s Brooklyn studio, we drink coffee on his white leather couch surrounded by the beautifully crafted collage pieces he’s been working on.

Influenced by his work with trans women in the community, they’re pieced together using jewels and photos from ‘urban glamour mags’ – like King and Black Lingerie – with the aim of sparking discussion around black bodies and agency.

“Our art has never been invested in,” says Rashaad, who’s been part of the voguing community for over 14 years.

“Can you make a living as a vogue dancer like you can with these Eurocentric art forms? No. Vogue was co-opted very early in its creation, like so many other things in black cultural history. But we can still push our art further, out of ballrooms and into galleries and art spaces.”

Later in the day, Derek takes me to another place featured in the documentary: the now infamous Village pier that serves as a congregation space for the community.

Gia Love at the pier in Greenwich Village, New York. “The first time I went to the pier, I was 14 years old,” she says. “It was one of the first times I had seen people like me or so many LGBT in one space socialising together.”

As the sun sets, it becomes a hive of activity: teenagers are voguing, discussing the cost of ’mones [hormones], yelling words of encouragement – “Your hair is cute”, “I’m gagging!” – while music blasts in the background.

It’s here, in the real world, away from cameras and exhibition spaces, where the community is truly coalescing.

Stepping into that world, even briefly, feels like glimpsing America’s future play out in its best possible light at a point in history when things could swing either way.

The more people you meet in the ballroom community, the more you hear stories of the moment someone walked into a space that transformed how they see themselves.

It’s those quiet, unassuming moments – moments of reflection amid something much greater – where self-determination can trigger a broader change.

“The first time I went to a ball, I was 14,” says Twiggy. “I was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’ On one hand I was afraid and overwhelmed.

“On the other hand, I was excited and felt celebratory because it’s so intense and so high energy. It was the most LGBT people I had ever been around in one space. I was like, ‘Who are these people? Is this who I am? Is this me?’”

This article appears in Huck 56 – The Independence Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop now or subscribe today to make sure you never miss another issue.

Find out more about Kiki the documentary. Check out photographer Krisanne Johnson’s portfolio.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.