'The engine, the motor, of Dylan’s best work is empathy'

- Text by Shelley Jones

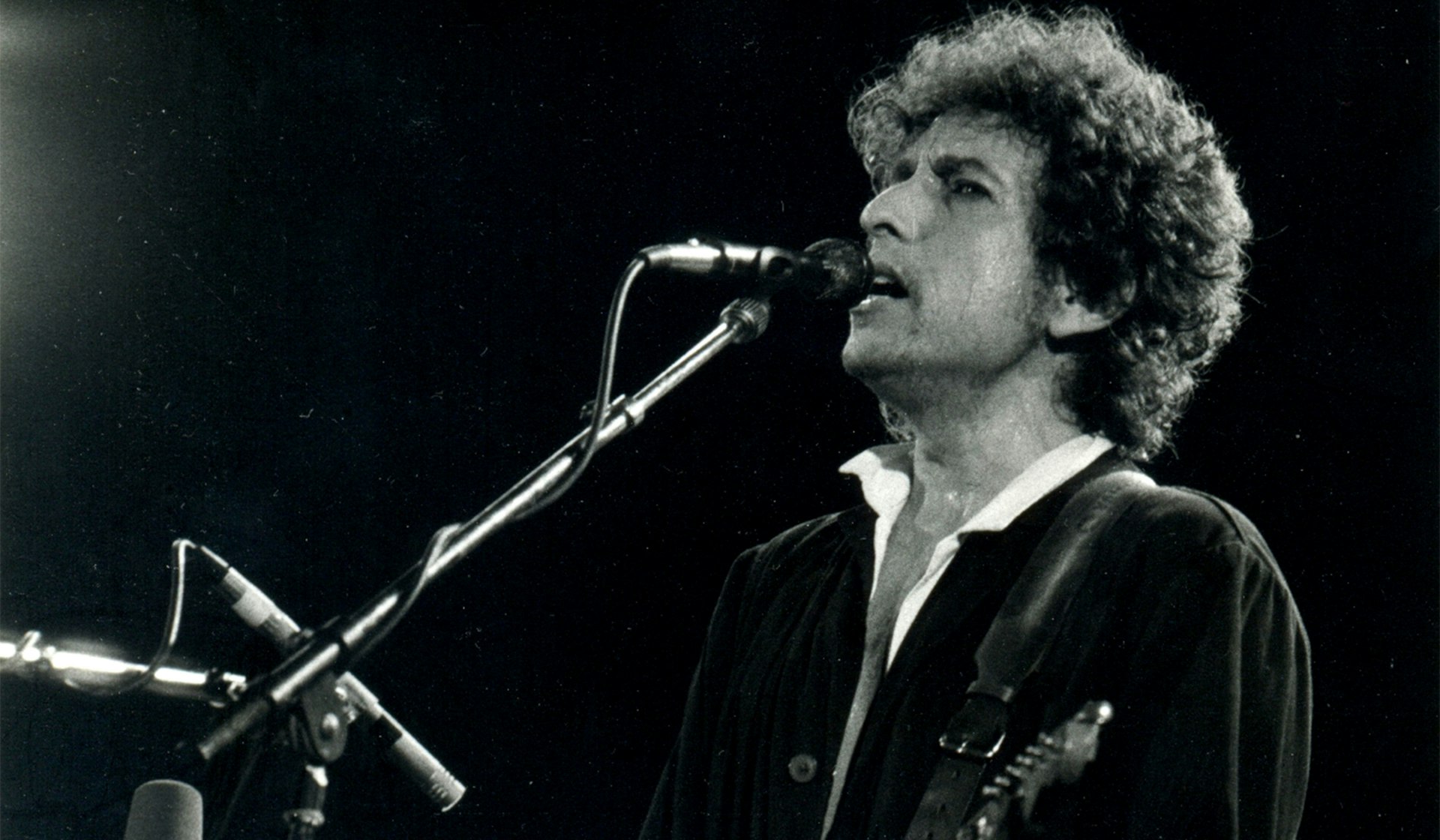

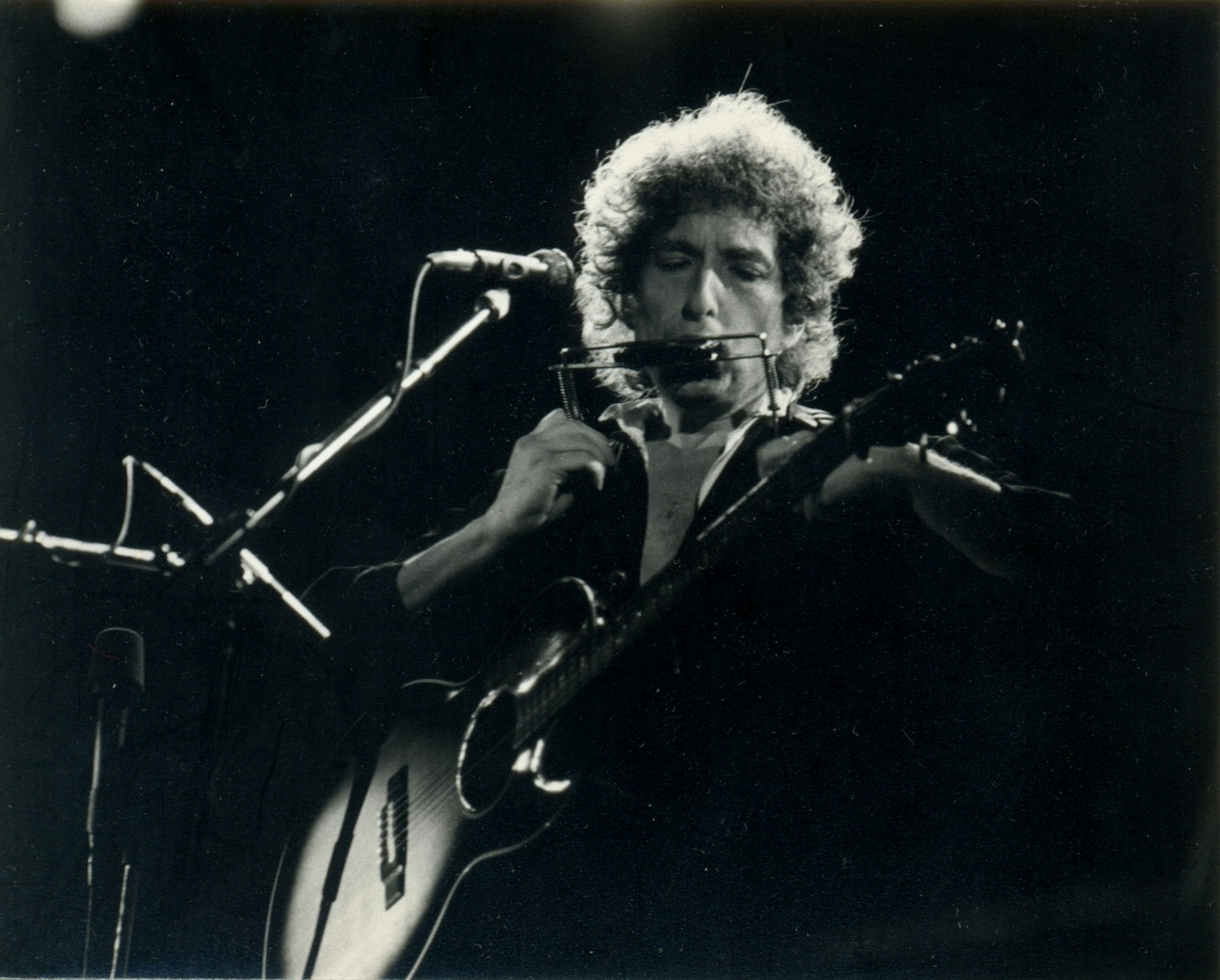

- Photography by Xavier Badosa

Chan Marshall is a pretty big fan of Bob Dylan. Having grown up with his records as a kid, and having covered a number of his songs as Cat Power, she’s continuously inspired by the dude she once called ‘God Dylan’.

Author, music journalist and cultural critic Greil Marcus is also a pretty big fan of the artist formerly known as Robert Zimmerman. Just four years his junior, Marcus began writing about Dylan in the ’60s and has, perhaps more than any other writer, been his most consistent critic. In 2010 he released his third Dylan book, Bob Dylan: Writings 1968 – 2010. We caught up with Marcus on the phone from Minnesota to chat about the sweet spot where Cat Power and Dylan connect.

Many people felt that Dylan embodied the counterculture of postwar America. Is he still relevant today?

I think the counterculture was a great slogan. Theodore Roszak came up with this slogan for his book The Making of the Counter Culture and it really caught on. I don’t think it was ever terribly thought through and I don’t think Bob Dylan would have said he was part of a counterculture, assuming there was such a thing, let alone a spokesperson for it.

The assumptions that held society together in the United States and all parts of the world were breaking up in the late ’50s and early ’60s. Things that people had taken for granted for generations were either being questioned or just didn’t seem to hold the kind of authority they had before and so you had society suffused with doubt and disillusion and a sense of betrayal, which was also at the same time extraordinarily liberating for all kinds of people. And so there was an enormous explosion of questioning, ‘Why do things have to be the way they’ve always been? Why isn’t another way just as valid?’ Whether it was a question of movies, music, sex, politics, economics, religion – all those things began to shudder and tremble as if there was this slow-moving earthquake spreading around the globe. Some people pretended they didn’t feel the tremors and other people said, ‘Not only do I feel these tremors but you can dance to them. I don’t want them to go away. I love this feeling.’

So, there’s no question that the music Bob Dylan was making in the ’60s, like the music that virtually anybody else was making, was affected by this. But Dylan was always talked about in that period as being a step ahead of everybody else. It wasn’t as if he was running a race; people thought of him more as a pathfinder – the Daniel Boone of the future.

And I think there’s some truth to that. The counterculture was creating its own stereotypes, its own repressive and imprisoning fixed ideas about the way things ought to be, and a lot of people bought into those myths: ‘The young are by definition the carriers of freedom’; ‘Black people are more real or authentic than white people’; ‘Poor people are less corrupt than rich people’ and so on. Bob Dylan seemed to carry with him a doubt that undercut the new clichés around him. A doubt that undercut those just as fiercely and directly and witheringly as what he brought to the pieties of the dominant society.

If you listen to ‘It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleedin’ it’s a litany, a laundry list, of everything that’s fake and phony and repressive in American society at that moment. It’s just this incredibly artless list and yet it has tremendous urgency; it’s impossible to get out the way of that song. At the same time, when you listen to ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’ or ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ or ‘Memphis Blues Again’ you hear the unthinkingness that so many people were bringing to a new culture being savaged just as powerfully.

Bob Dylan, I don’t think, ever wanted to be relevant in the conventional sense of the word. He never wanted to be a force that could be brought to bear on this issue or that, as someone who had answers. A lot of Bob Dylan’s best songs don’t even have questions let alone answers.

Your book Bob Dylan: Writings 1968-2010 ends with a description of Dylan performing ‘No More Auction Block’ – a traditional African American folk song. Do you think Dylan brought black and white culture together?

He has brought that music together in his music, but I don’t think you see all that many black people at his shows. So, in some ways, that’s two different questions. He hasn’t united an audience except perhaps in his own imagination. I always think that he sees his audience as made up of the people that came before him, the people he draws on and honours in his songs – the people whose songs he rewrites and rethinks. Whether it’s Charlie Patton, Emry Arthur or Robert Johnson – Bing Crosby or any number of people from the past – I think those are the people to whom his songs are really addressed, whether on record or at the shows, in the deepest sense.

So in that sense, sure – he has maybe, as much or more than anybody else, brought the disparate musics of the United States, black or white, Northern or Southern, together. But what people make of it is another question. And in terms of what’s going on today, who knows? Maybe you could say that Kanye West and Jay-Z and Beyonce have done more to bring black and white culture together because their audiences are made up of black people and white people. Their audiences are far more disparate and racially mixed than Bob Dylan’s.

Chan often quotes something Patti Smith said to her: ‘We’re artists, we have responsibilities…’ But Dylan famously said he didn’t owe the world anything. Do artists have responsibilities?

That’s such a typical Patti Smith thing to say. It’s full of self-importance, it’s full of self- congratulation. Artists have a responsibility to their work – to offer the public and themselves the best they can do and as much as possible, when you have something you know isn’t good, when you have something you know is ‘fake’, not to put it out. And that’s very difficult to do sometimes… Throughout this conversation you’re kind of looking for a way to say, ‘Is Bob Dylan true to the legacy, true to the responsibilities that other people have projected on him?’

As far back as 1965, in a press conference in San Francisco Dylan was asked, ‘Are you going to be attending the anti-Vietnam rally march tomorrow?’ And clearly the feeling was Bob Dylan oughta be there. Bob Dylan is a leader of the counterculture. He is a prophet of rebellion. Of course he’s opposed to the Vietnam War. ‘You need to be there! You have responsibilities!’ And Dylan said, ‘Youknow I don’t think I’m going to be able to be there.’ And the same questioner said, ‘Well, is there any kind of march you will take part in?’ And he said, ‘Oh yeah, I think we should have a march where people come and make up their own posters and signs.

But these signs would have playing cards on them like the Jack of Diamonds, or maybe just some punctuation marks, question marks, maybe just single letters. And these would be the signs that people would be carrying.’ You can listen to that answer and think he’s making fun of people asking the questions or you can think he’s actually imagining a march that might be tremendously interesting and effective, but on completely different terms. A march that is simply asking questions. And that is asking questions about the questions that other people are asking. What does that mean – ‘Artists have responsibilities’? Patti Smith has spent a lot of time going around telling people to vote for Ralph Nader, well that got us George W. Bush as president. Are those the kind of responsibilities we want our artists to have? I don’t! Artists are responsible to their work. And that’s it.

You once reviewed Cat Power’s version of Dylan’s version of the old folk song ‘Moonshiner’. How did you feel when you first heard her cover?

I was in Memphis and I met this woman who was telling me that she’d come to Memphis from New York, where her life had reached a dead end. She’d lived there for a number of years and the town had sort of given her nothing back. She said, ‘This place is just a desert. And the only way I can get out of it is to listen to music that is even more desolate than I feel. So I listen to Cat Power.’ And I said, ‘Oh, who’s that?’ And she said, ‘You’ve never heard of Cat Power? You better find out.’

So when I got home I got her records and started playing them. I fixed on [Moon Pix] which featured her version of ‘Moonshiner’ and I thought, here’s an old folk song that Bob Dylan sang in a way that no one else had ever sung it before. He sang it with more delicacy and more regret than anybody had ever thought of doing and he sang it as if it was absolutely true. He wasn’t pretending to be a moonshiner, he absolutely was a moonshiner; somebody looking back on his own life. It was this incredible feat of empathy, of transformation, and some of the best singing of his life.

So, here’s this old handed-down song that he made impossible for anyone else to ever sing again and then here comes this young woman with the nerve to try and sing it again. And she manages to not so much go up against Bob Dylan as to walk around him and come out on the other side. You don’t care what anybody did with the song before. This is someone who heard it, who understood it, in a way that nobody had before and they were able to get that across. And I thought, ‘This is just so remarkable. This is the way it ought to be.’ And I knew from that moment on that whatever she did I would always want to hear it, whether I liked it or not.

One of the interesting things about artists is that they know things that other people don’t. Whether it’s an emotional reaction, whether it’s an intellectual insight. And the reason they’re artists is because they want to tell other people what those things are. They want to communicate them. They’re saying, ‘This is what the world looks like to me.’ And what Cat Power was doing with that song was communicating the way the world looked to her and it looked different than it had looked to Bob Dylan… It’s rare that someone can do that with the force that she was able to bring to bear on that performance. So, from that moment on I felt like, ‘I want to hear what this person does. She knows something I don’t.’ And it’s not that I want to find out what that is, because it’s no single thing, but I want to be part of that conversation.

You talk of how Dylan’s genius lies in his empathy for different characters, but some people argue that his female characters are not as interesting as his male ones. What’s interesting about Cat Power is that Chan is able to add a female perspective to the themes Dylan explores in his work. Would you agree?

I don’t know that there’s any such thing as a female perspective or a male perspective. I do know from long experience that when you put together a panel, any kind of group of people discussing a topic, there are certain questions that will never get asked if you only invite men. There are certain points of view that will never be expressed. There are certain attitudes that will always be absent. It doesn’t matter how sensitive, how sophisticated, how thoughtful four or five people are, it just won’t happen…

But you’re asking about Dylan’s characters, his point of view. That’s a hard question to answer. The same question can and has been said over and over about Philip Roth, that his female characters are caricatures and his male characters are the ones who are really alive. I’m not sure that’s true, I’m not sure that isn’t true. It would seem to me that Cat Power is able to bring a sensibility of jeopardy, or woundedness, of damage, to her music and the songs of other people that she sings, that is a large part of her contribution.

I think of the movie North Country with Charlize Theron – ‘Paths of Victory’ I think is the song that plays over the credits. A Cat Power version of a Bob Dylan song. Charlize Theron gives a tremendous performance in this very small, modest movie; she has kind of a husky voice in the same way that Chan does, and when you hear that song in the movie you think it’s Charlize Theron who’s singing it. That connection between the singer and the actress has been made so strongly, so powerfully, that any difference between them disappears. And that kind of empathy is really rare; it’s Cat Power’s empathy for the song and anybody it might speak for.

I really think that the engine, the motor, of Dylan’s best work is empathy. His ability to put himself in other people’s shoes. If you listen to ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, which is addressed to this female character, you could hear it, as so many people have heard it, as this expression of rage and contempt. The whole song is this one overwhelming put-down. But I never heard the song that way.

I hear somebody saying, ‘Look out! You’re going to get run over! This is terrible! Get out of the middle of the street! Look around you! There’s trouble coming from all sides!’ And you could say that quality of empathy is very feminine, very female. I think that’s a reductive way of looking at the world, but if you want to raise those kinds of questions, Dylan’s gift of empathy, or his craft of empathy, is maybe what he and Cat Power share, and she from a more weary distance than him.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Greil Marcus is the author of The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs, published by Yale University Press and Bob Dylan: Writings 1968 – 2010, by Greil Marcus, published by PublicAffairs Books.