Ed Templeton on Larry Clark's renegade style of photography

- Text by Ed Templeton

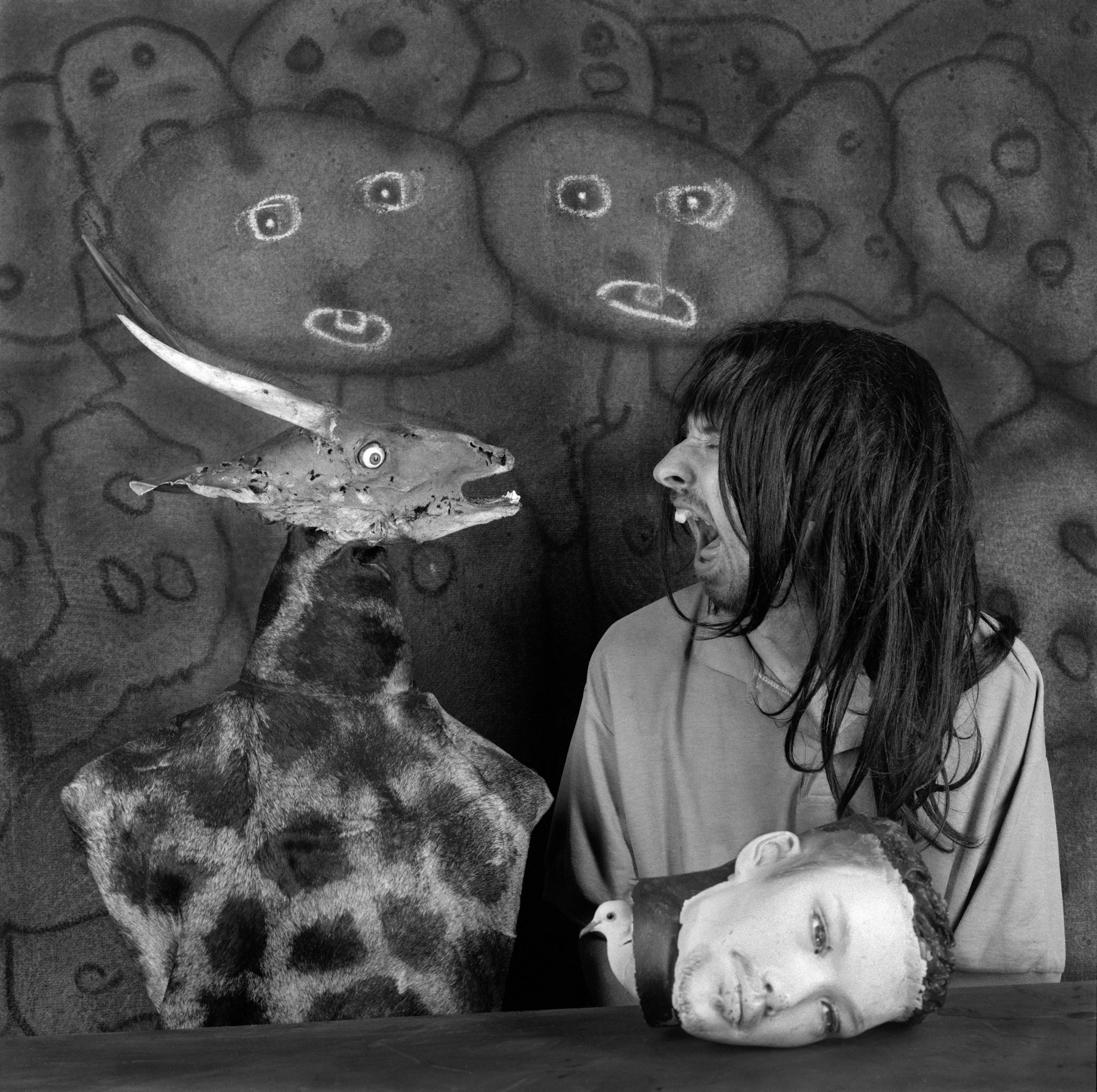

- Photography by Ed Templeton (main image)

Hordes of photographers from my generation cite Larry Clark as an influence, and almost inescapably I am no different. The raw authenticity of his legendary books Tulsa (1971) and Teenage Lust (1983), once consumed by a young photographer, stays in the stomach undigested and serves as a clarion call to immerse yourself in a lawless druggie culture – even if, as in my case, you don’t do drugs and have no access to a drug scene.

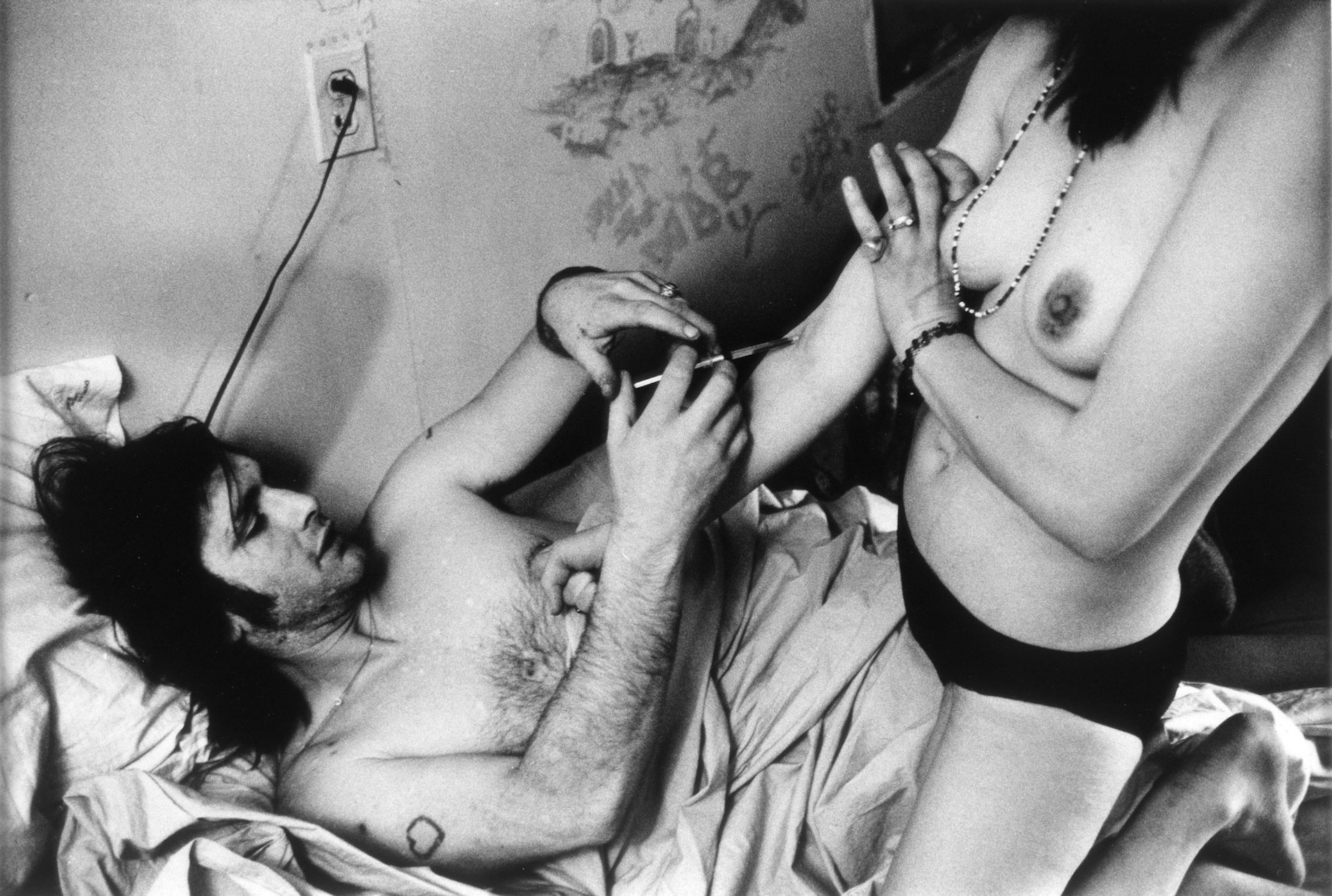

Two images in particular encapsulate the ideas portrayed in LC’s work. In one, a man laying in bed with a shitty homemade heart tattoo is straddled by a topless woman who extends her fist towards his chest to stoke the veins in her arm.

Untitled, 1971. Courtesy of Larry Clark, Luhring Augustine, New York and Simon Lee Gallery, London/Hong Kong.

The man is plunging a syringe filled with heroin into her skin as a beaded necklace rests in her cleavage. The scuffed wall in the background has words scrawled on it and an outlet has a cord plugged into it pointing right back at the man’s head. The content, composition and message it sends is perfectly executed. The photo explains itself without my help.

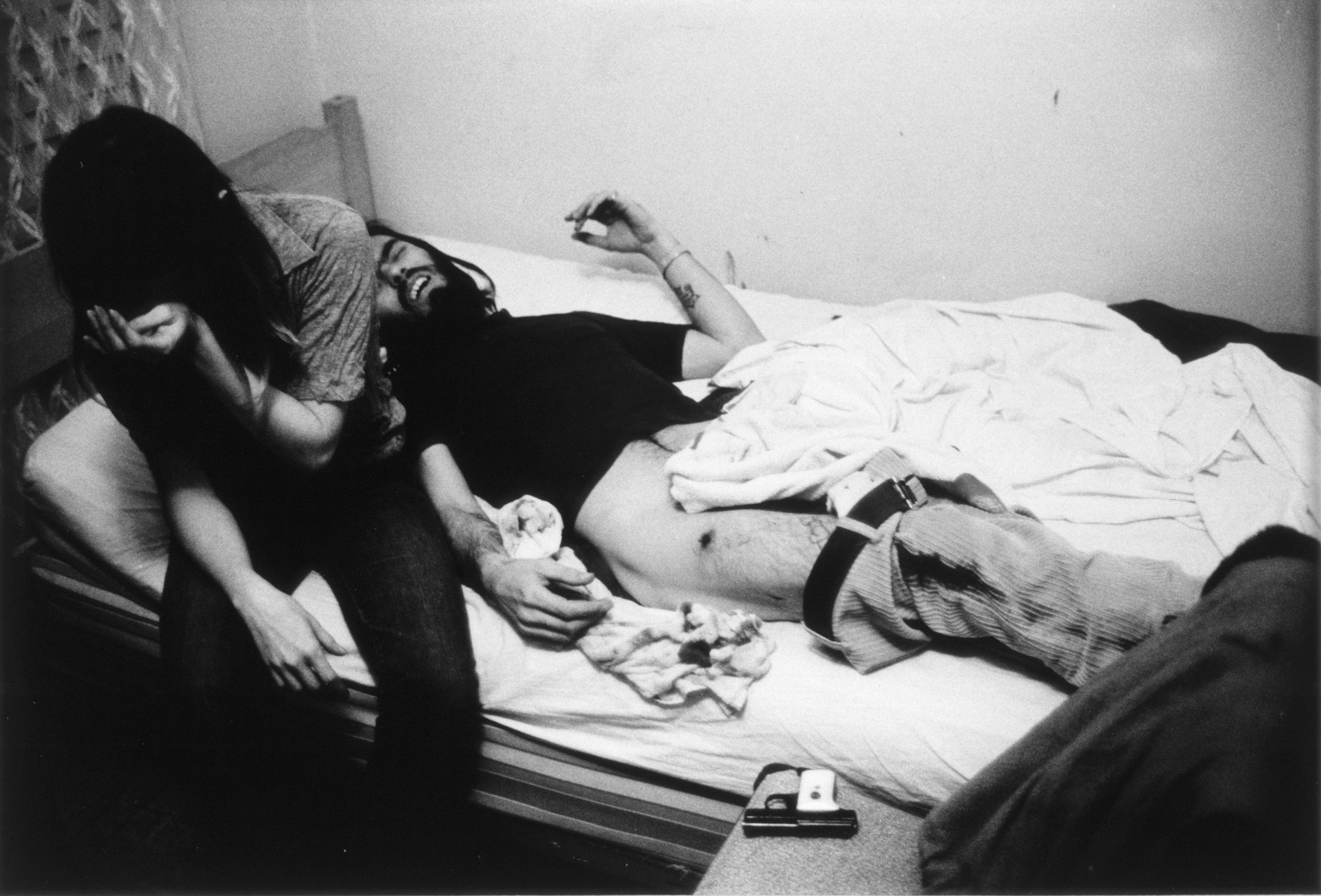

In the other, a man lays on a bed with his pants pulled down to his knees and a visible gunshot wound in his thigh. He’s grimacing with pain while a girl sitting on the edge of the bed puts a hand on her face, seemingly in despair. The caption in the book says, ‘Accidental gunshot wound.’ The presumed culprit, a tiny gun with a white handle, rests on a chair in the shot.

Accidental Gunshot Wound, 1971. Courtesy of Larry Clark, Luhring Augustine, New York & Simon Lee Gallery, London/Hong Kong.

The image not only documents an accident and illustrates the culture these people are in, it also begs so many questions. Why do these kids have guns? How did he shoot himself or get shot by accident? Was it the girl who shot him? Does she feel guilty now? If they are criminals, will they be able to go to the hospital with such a wound without getting busted?

Clark was clearly a participant in the sex and drugs documented throughout his photos. These were his friends and he just simply shot pictures of the daily life they were living like a fly on the wall. But he knew exactly what he was doing. These aren’t amateur compositions by some fuck-up with a point-and-shoot. They’re in focus and correctly exposed.

What he chose to shoot shows that he knew that the life he was living was extraordinary and a story worth telling – so much so that in 1971, when Tulsa came out, it scratched a little too deep below the surface for polite society to handle. It created a splash that rippled through the art world and into popular culture.

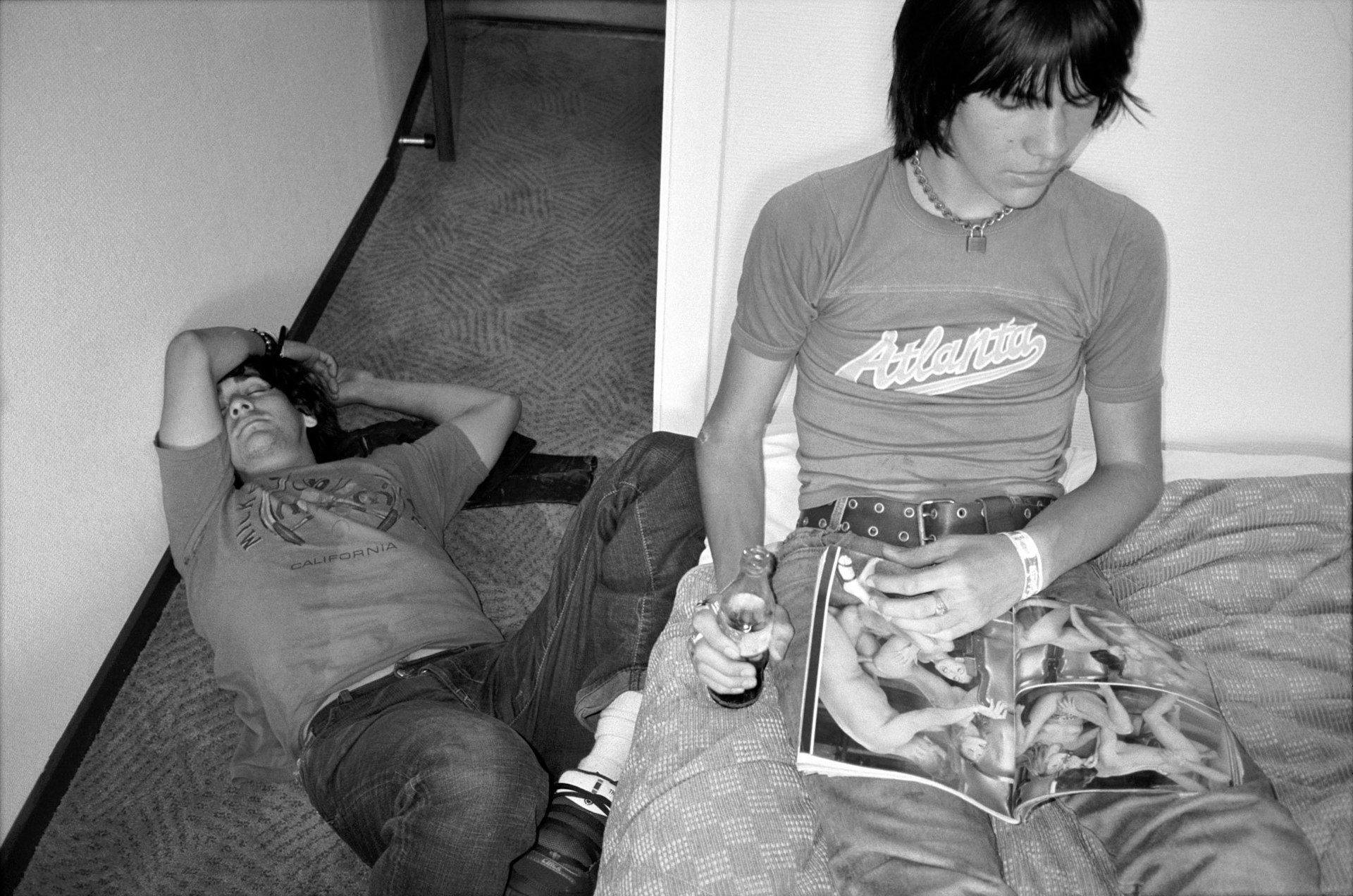

Jack and Lynn Johnson, Oklahoma City, 1973. Courtesy of Larry Clark, Luhring Augustine, New York & Simon Lee Gallery, London/Hong Kong.

The trail of influence is abundant. Gus Van Sant and Martin Scorsese, whose respective films Drugstore Cowboy (1989) and Taxi Driver (1976) were directly influenced by this work, which in turn influenced Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994). It’s like nobody knew these people existed and were horrified to realise that things like this happened behind the closed doors of innocent America.

Today, 46 years on from Tulsa, we now live in a world where everybody broadcasts their lives, extraordinary or not, and there is no underground culture to document that isn’t being covered via iPhone by its own participants, if you know where to follow them.

For me, the Clark inspiration manifested itself in the way he got those photographs. Growing up skateboarding in the affluent suburbs of Southern California, I wasn’t going to experience anything like Larry Clark’s world. But I could shoot my scene and friends just as he did, and take it seriously.

I went pro for skateboarding in 1990, and was exposed to LC’s work around 1993. It was then that I recognised that the subculture I was participating in was filled with extraordinary people and had its own visual language worthy of documentation.

Larry thought so too, because it was around this time that he began looking at skateboard culture in NYC and developing his future film Kids (1995), a project spurned by jealousy after Gus Van Sant basically ripped off his imagery. He wanted to do it himself.

It was that idea that turned me on to photography and my interests have since branched out from that in many directions. So, thank you Larry Clark.

This article appears in Huck 62 – The Documentary Photography Special V. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Huck’s Rule-Breakers: The Exhibition takes place at London’s 71a Gallery on Thursday 9 November.