The magic and mysticism of modern-day Hinduism

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Abbas / Magnum Photos

In a world increasingly dominated by science and technology, how can we explain the enduring presence of the non-rational: religion, mysticism and ritual?

That’s the question that motivates Iranian Magnum photographer Abbas, who has spent almost four decades exploring contemporary religion around the globe.

Following on from his ongoing study of Buddhism and Allah O Akbar: A Journey Through Militant Islam, his latest project Gods I’ve Seen: Travels Among Hindus took Abbas through India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bali to document modern observers of what many call the oldest religion in the world.

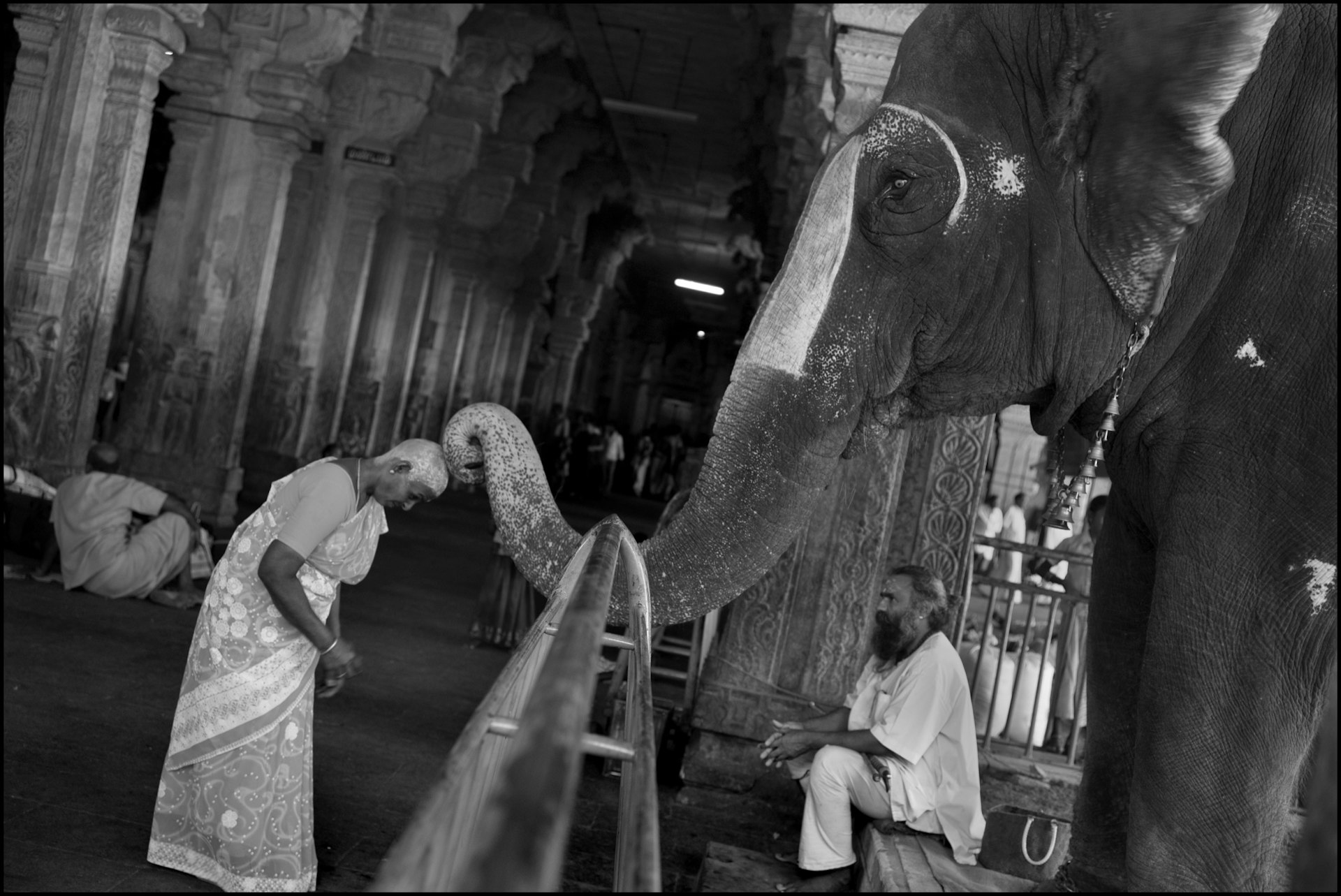

At the Sri Ranganathaswamy temple, an elephant blesses a pilgrim with its trunk after receiving a cash donation. The pilgrim has offered her hair to a resident deity, and her shaved head is covered with tumeric paste for protection; Tiruchirapalli (Trichy), India.

In the Golden Temple, the Sikhs’ most sacred place, a pilgrim holds a leaf to receive the morning darshan (food offering); Amritsar, India.

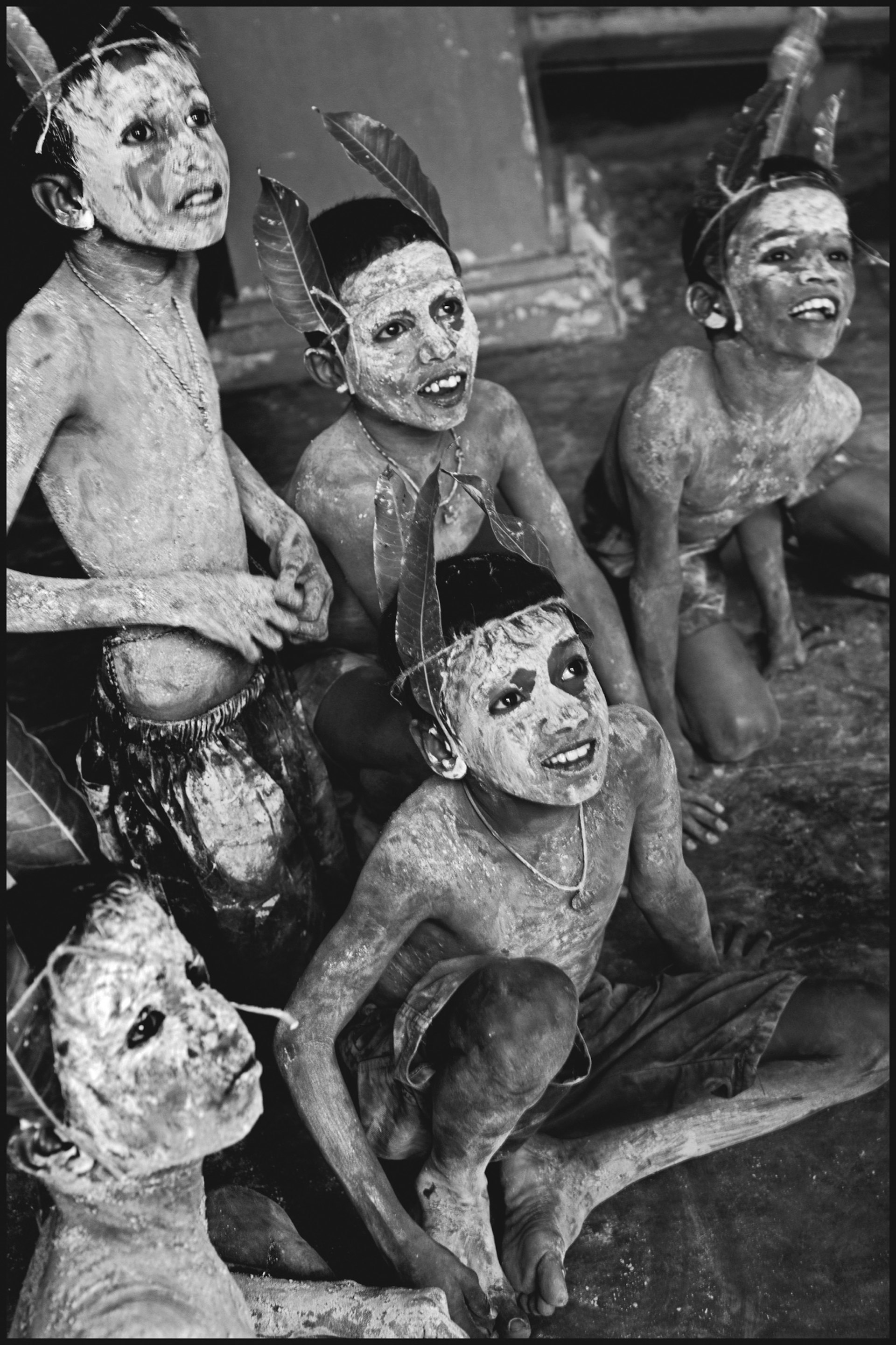

One billion followers practice the rites of Hinduism and Abbas set out to investigate and record the mysteries of the faith: its magic practices; wind, water, earth and fire rituals; and spiritualism around animals.

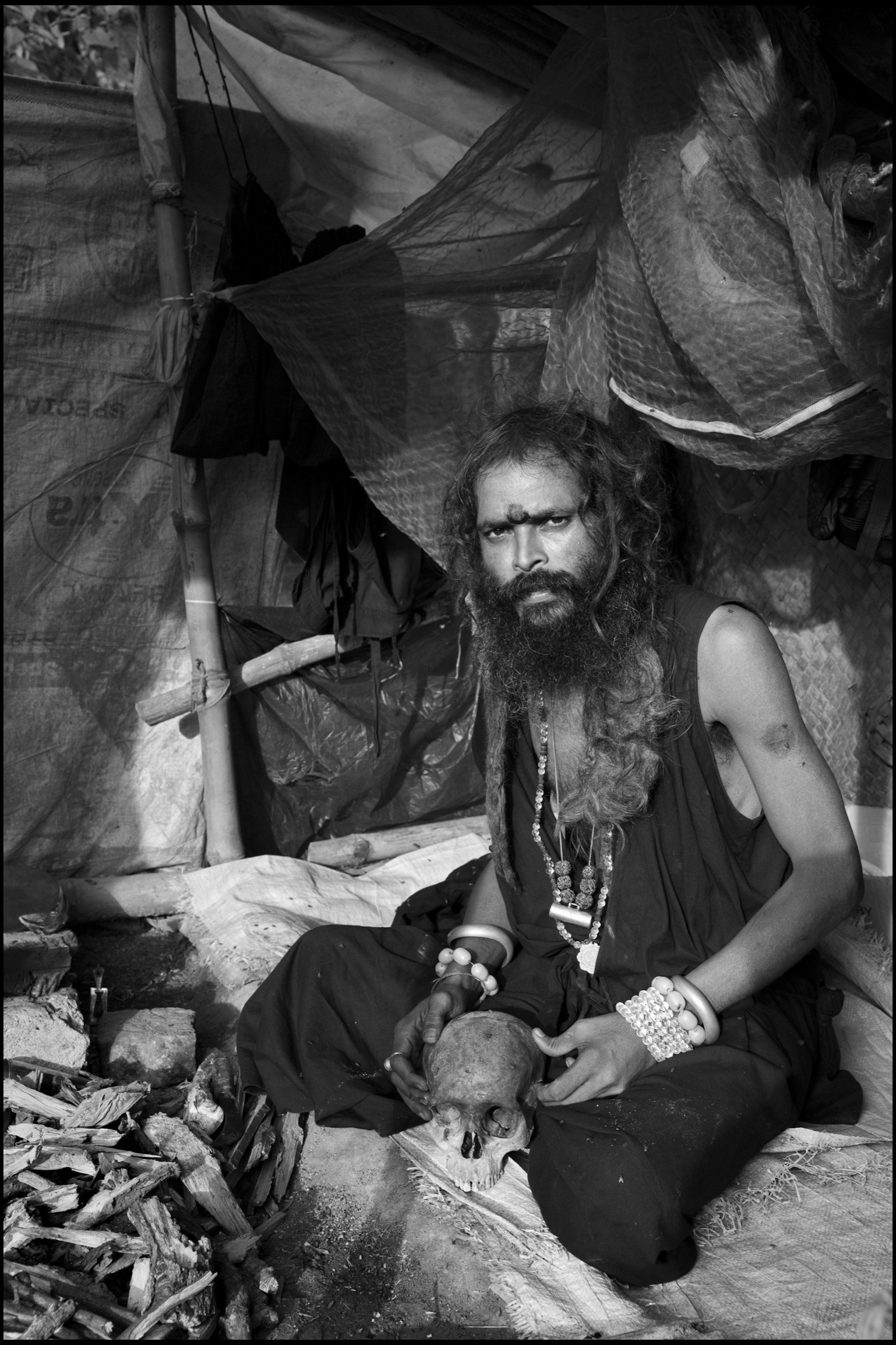

In Tarapith, India, Abbas encountered a Tantric sannyasi who uses the skull of a dead guru to enhance his spiritual powers during meditation; a man hanging from hooks pierced into his skin in Colombo, Sri Lanka; and naked worshippers rushing into the holy waters of Allahabad.

Abbas’ striking black and white images construct a thought-provoking and meditative study of contemporary faith that avoids the exotification and romanticisation present in so much photography of the region.

In the grounds of the Bamakhepa burning ghat, a Tantric sannyasi uses the skull of his dead guru ‘to enhance his spiritual powers’ during meditation; Tarapith, India.

After your work on Buddhism and Islam, what particularly stood out to you about Hinduism?

Their 330 millions gods, but unfortunately I could not photograph them all.

Which aspect of the Hindu religion did you most enjoy documenting?

The Hindus’ relationship with animals – a whole chapter is dedicated to the subject at the end of the book. You can also ask me what aspect I enjoyed least: the ever-present squalor!

Steve McCurry and others have come in for criticism of their Indian photography for romanticising traditional elements to create a picturesque, exoticised image of the region. What did you do to ensure a you presented an honest reflection of contemporary Hindu nations, and avoided romanticisation and exoticisation?

It is indeed easy to make India and Hindus look exotic with colour. I use black and white, which does not show reality but transcends it, allowing the reader many layers of meaning. At the end of the book, among the diaries, there are ten colour photos, because in India, colour was a challenge I could not ignore. But these photos are not part of the discourse, colour is the main character.

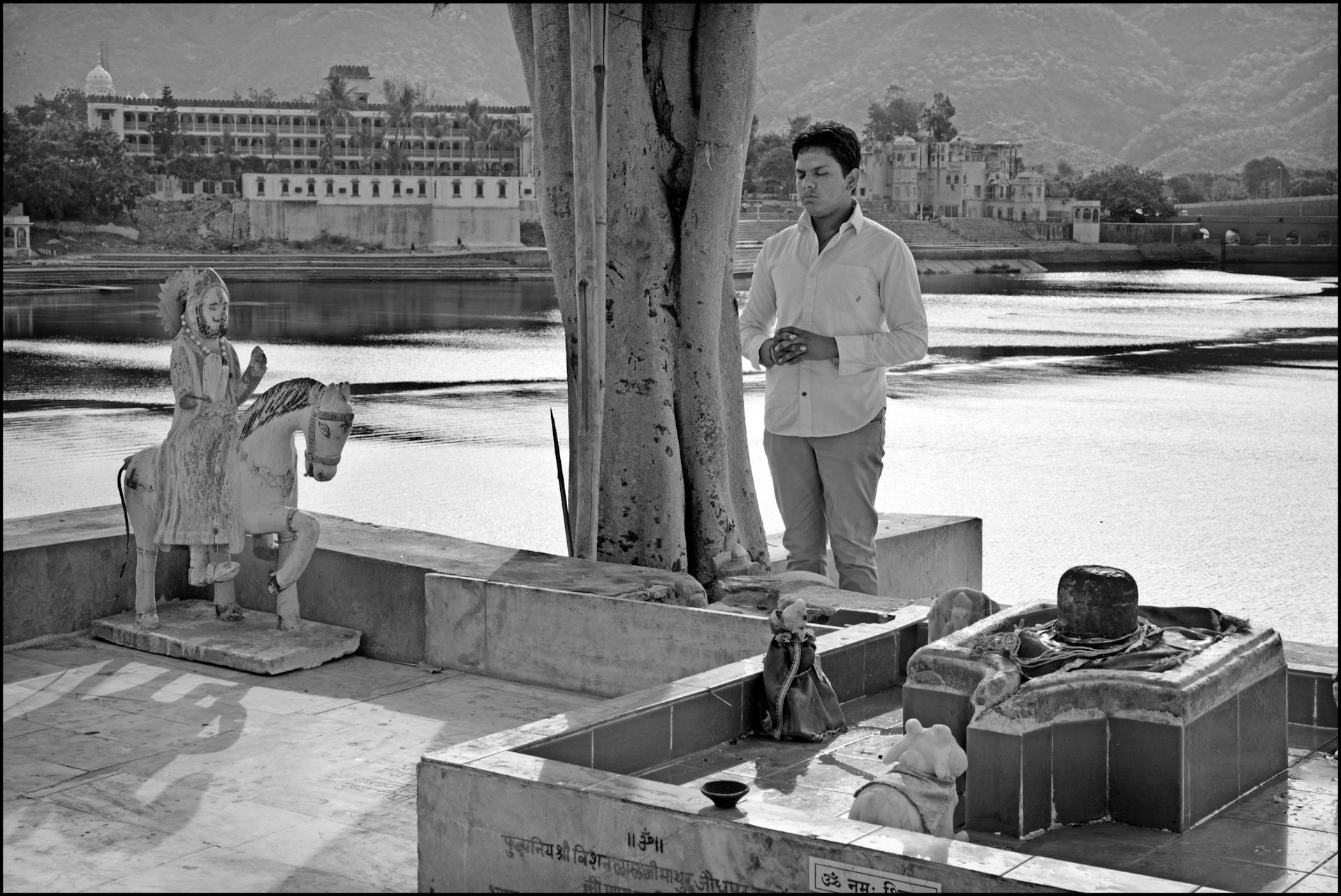

At dawn, a devotee prays at an altar by the lake; Pushkar, India.

Sixteen days after the cremation, ashes and three bones from the deceased are thrown into the sea; Varkala, India.

You’ve spent a lot of time documenting societies in conflict. How does the role of religion change in wartime, compared to peace time?

It can exacerbate a nationalist conflict, as in Sri Lanka, where the rebel Tamils were mostly Hindus, while the majority of the population was Buddhist. It can also help soothe the wounds of war, as in South Africa, with the truth and reconciliation commission whose inspiration was Christian: if you confess you are forgiven.

Have your travels in recent years brought you any closer to an understanding of what motivates people’s faith?

If I found out, I would stop photographing religions. I can rationalise men’s needs for god (magic, solitude, eternity, spirituality, the stick) but faith is still a mystery to me. It is less faith I am interested in than what men do in the name of god, the gods: some of the great achievements but also their stupid and violent actions.

How does religion endure in our modern, (supposedly) rational world?

I would like to say, ‘too much for my taste’ but then, if there was no religion, I would be out of business. It is mildly ironic that I am writing to you from Jerusalem, a city which has such a long memory of religions.

Students from the Indonesia Institute of Arts dress up for a rejong traditional dance in the Batur temple; Kinmantan, Bali.

Gods I’ve Seen: Travels Among Hindus by Abbas is published by Phaidon.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.