A photographer's portrait of America in the post-truth era

- Text by Adam White

- Photography by Max Pinckers

It’s the morning after Donald Trump’s election on a street in West Hollywood, where a woman with tears in her eyes grasps onto a man and shares an emotional embrace. But only some aspects of this image, captured by artist and photographer Max Pinckers, are in fact real.

It is indeed the morning of a new dawn in American politics, and the emotions captured are more or less reflective of half of the country, but the couple are strangers – actors, to be more specific, posing under direction from Pinckers. The image may be someone’s version of the truth, but it’s certainly not truth as we know it.

“When it comes to photographs and images, I think they communicate a lot more than simply representing what is shown,” Pinckers says. “It works on many different levels, and our imagination or our way of seeing can be in flux with many different things. A lot of the time it projects what we’re already looking for, or to confirm what we already believe.”

Over the phone from Greece, the Brussels–born Pinckers is talkative and entertaining company, often expressing his surprise at being an unintentional soothsayer.

The photographer has long explored the blurring of fact and fiction in his work, particularly his belief that documentary photography has become distracted by aesthetics in an era when everyone has access to a camera.

But his latest project, Margins of Excess, feels directly attuned to the political climate of today, where truths, half-truths and outright lies have slowly congealed, creating a new normal defined as “post-truth”.

It’s a term often associated with the world’s most powerful, but Pinckers has focused his new work on largely inconsequential individuals – people who’ve created their own version of reality and who defend it vigorously, even when it seems like the whole world has turned against them.

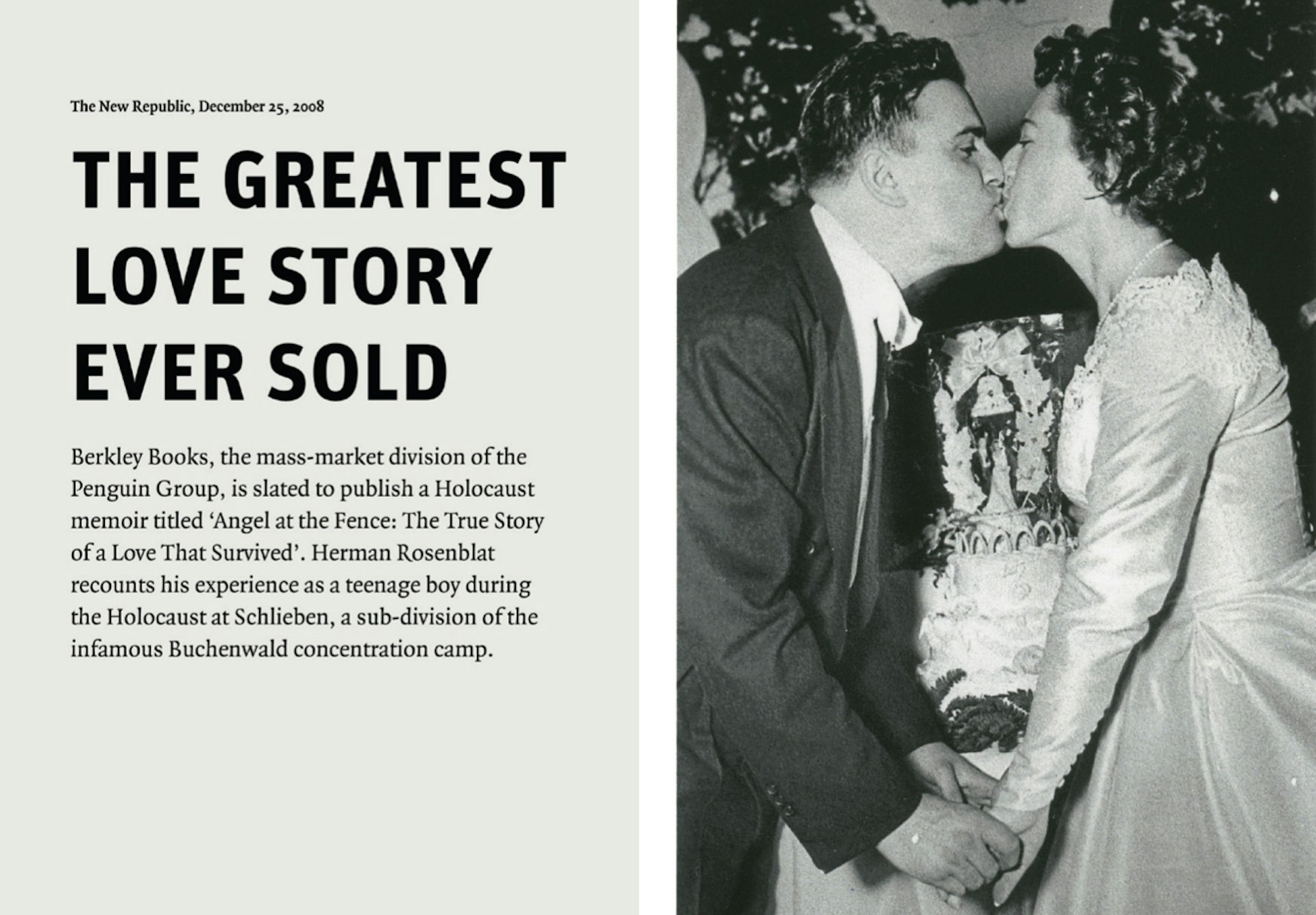

One is a Holocaust survivor named Herman Rosenblat. His story centres on the claim that, in 1995, he married the same girl who regularly passed him food through the fence of his WWII concentration camp.

Two decades later, with a memoir in the works, he confessed that the story had been distorted. Speaking to a journalist in 2009, Rosenblat argued that “it was not a lie, it was in my imagination; but in my imagination, in my mind, I believed it.”

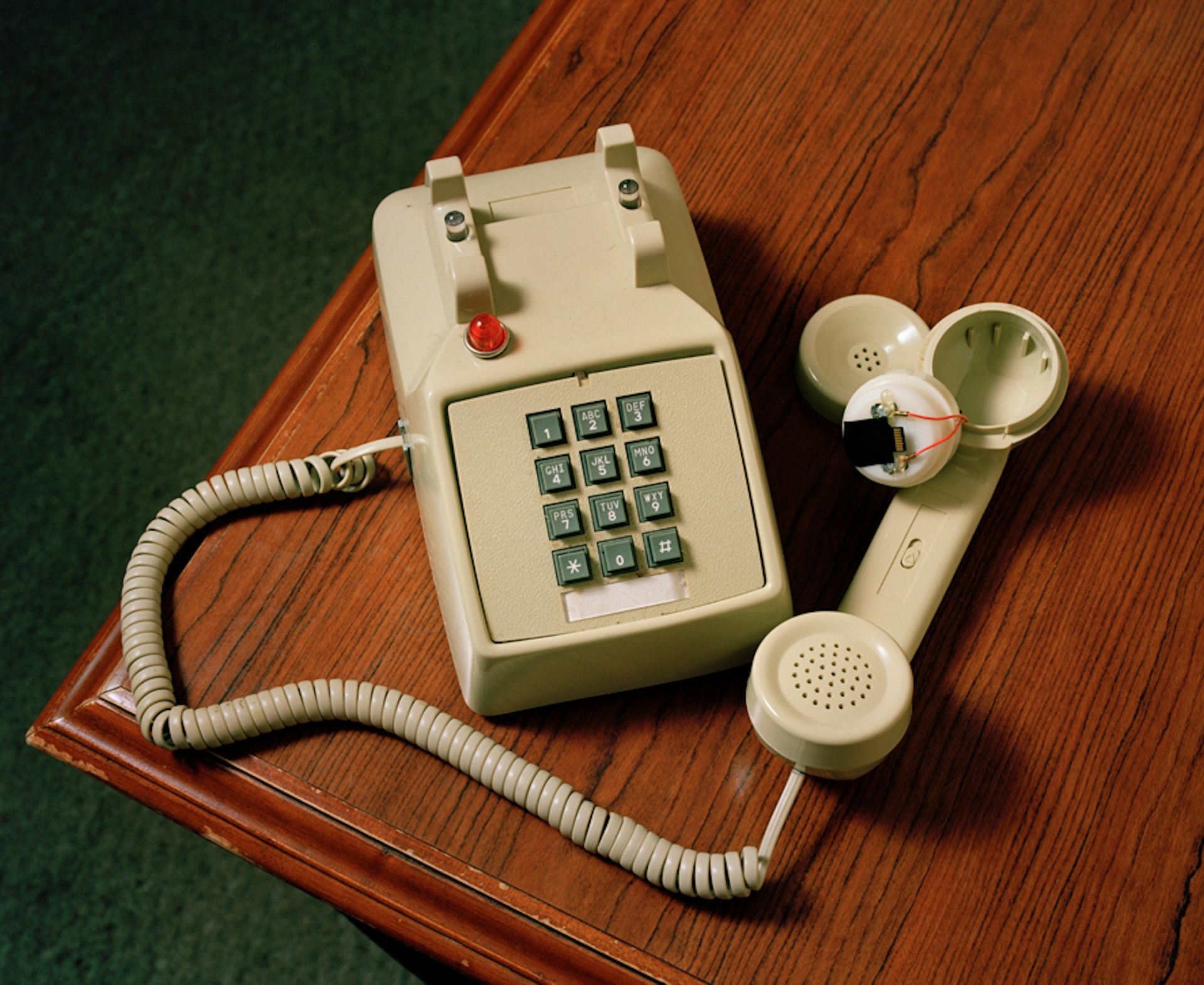

Other figures include Darius McCollum, a man with Asperger’s who became a folk hero for his involvement in over 25 hijackings of the New York transit system. “[An article] said that I was an impostor,” he tells Pinckers. “I wasn’t impersonating somebody else; I was impersonating myself.”

Then there’s civil rights activist Rachel Dolezal, who found infamy when a news reporter discovered that, despite presenting as a black woman, she was actually born to two white parents.

Elsewhere, a double-hand amputee and private detective named Jay J. Armes fully embraces the superhero-like mythology built up around him in the 1970s, while Richard Heene, the father involved in the 2009 ‘Balloon Boy’ hoax, continues to deny that he knew his young son was hiding in the family attic and not, as he claimed, trapped in a helium-filled gas balloon flying high above Colorado.

The project began when Pinckers was awarded a six-month artists’ residency in New York, inspiring him and his wife (photographic assistant Victoria Gonzalez-Figueras) to explore quintessential American subject matter for the first time.

Ideas began to percolate when they discovered the story of Richard Jewell, a security guard briefly accused by the media of being the mastermind behind an attempted bombing at the 1996 Summer Olympics – a potential tragedy that Jewell had himself averted. But the story was too one-sided, Pinckers found, with Jewell’s reputation unnecessarily destroyed by a mob of reporters baying for a scoop.

“We wanted to find stories where it wasn’t so clear what happened,” Pinckers says. “We didn’t want to indict anyone, but instead find this in-between space. We ended up looking for stories where people have accidentally landed in the spotlight, where the news and the media start to pick up on it, and then the people themselves start to play around with that attention.”

Darius McCollum, a man with Asperger’s who became a folk hero following 25 hijackings of the New York transit system.

Margins of Excess, named after the context and physical objects that surround a photograph’s subject, came into focus soon after. Apart from Rosenblat, who died in 2015, all of the proposed subjects were alive and willing to talk – particularly since Pinckers approached them as an artist, rather than as a journalist.

Upon meeting them in their homes (or, in McCollum’s case, prison), the photographer snapped their portraits, before recording lengthy monologues in which his subjects talked about their identities and what led to their current circumstances. He let them speak without interruption and avoided asking direct questions.

“I deliberately didn’t want to create an interview situation where they would have to almost explain themselves again,” Pinckers says. “I was also interested to see how they would, with a completely clean slate, communicate their story. Once you start asking questions, you start directing the story in a certain way, like you’re looking for something.

“But it’s interesting to see what they come up with when they don’t have questions. It’s also about providing a space for them to say what they want to say, and then have that put alongside the version that comes out in the newspapers, so you can see what they’ve chosen to focus on.”

Free of interrogation, Pinckers’ subjects alternate between playing up their reputations, contradicting past statements, or finding freedom in finally being allowed a platform. That lack of challenge proves fascinating, but often infuriating.

Dolezal compares her ethnicity to historical cases of black Americans “passing” as white, often to gain employment or security, but argues that it is only “taboo” when it goes the other way. She uses language typically associated with the trans community, and calls herself a “pioneer”. Heene avoids specifics about his son’s disappearance, but repeatedly claims the incident wasn’t a hoax, along with parroting online conspiracies about “fake news”.

As a result, Margins of Excess often speaks to how we create our own truths, consciously or not, as a form of protection. Dolezal and Heene are the most combative of Pinckers’ subjects, blaming the media for their personal woes, from Dolezal’s loss of employment to Heene’s prison sentence for attempting to influence a public servant.

Having both experienced scandals in the age of the 24-hour news cycle, they argue for more responsibility when it comes to the potential destruction of lives. Pinckers, however, is keen to emphasise that Margins of Excess isn’t designed as a condemnation of the media.

“I didn’t want to undermine the position of journalists, because a lot of the time they ask the right questions in order to get to the essence of the story, and I think that’s very important,” he insists. “I wanted to hear what these people had to say because of their amazing perceptions of the world and of themselves. And you can read it from different perspectives.

“Maybe a journalist will read it from the position that they were happy with how the stories were handled. But on the other side, if you are very anti-media, you might be looking for how the news has failed here and there, confirming that narrative in the book.”

But while the Trump administration is often blamed for the current climate of confusion, Pinckers highlights that the illusion of truth has long been built into the American landscape. Organised like a breathless tapestry of photographs, newspaper clippings and staged scenes, Margins of Excess folds in historic UFO hoaxes, religious miracles, jingoistic hyperbole and the terrifying spectre of the unmarked white van.

It portrays a country that has always existed in service to its own mythology, regularly mixing fact with fiction – a balance that has only recently been weaponised with such aggression. For some, amid so much noise, the safest place to reside is in the truth we determine for ourselves.

“It’s a hyper-individual culture we’re living in today, where the only truth is people’s own feelings. Each of these characters [in Margins of Excess] is pulling that to its extreme, shaping their own worlds and making their own truths. But I don’t know if that’s a good thing. It’s very easy to manipulate people’s desires, what they would like to believe. That’s something that Trump really mastered somehow.”

Despite his eerie ability to anticipate the post-truth era before it took hold, Pinckers is reluctant to share much of his vision for the future, but admits he is anxious about the virtual space, the extremism it breeds, and its tendency to disconnect individuals from the world. Right now, he says, he just wants people to pay attention, to look closer at the grey area we all inhabit.

“It’s a consequence of the simplistic narratives that we’ve been given for a very long time,” he explains. “In a very broad sense there’s always a good and an evil. There’s always a good guy and a bad guy, there’s a fraud and there’s a truth.

“But it’s really not that simple, and I think we have to get away from those almost trope-like narratives that we maybe look for to try and simplify things. We should just embrace complexity and also acknowledge that there are many things we may not understand or may not know. Don’t take for granted what you’re being told to believe.”

This article appears in Huck 66 – The Attitude Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Margins of Excess is self-published by Max Pinckers.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.