Syd Shelton's iconic images document Rock Against Racism from the inside

- Text by Sam Warner

- Photography by Syd Shelton

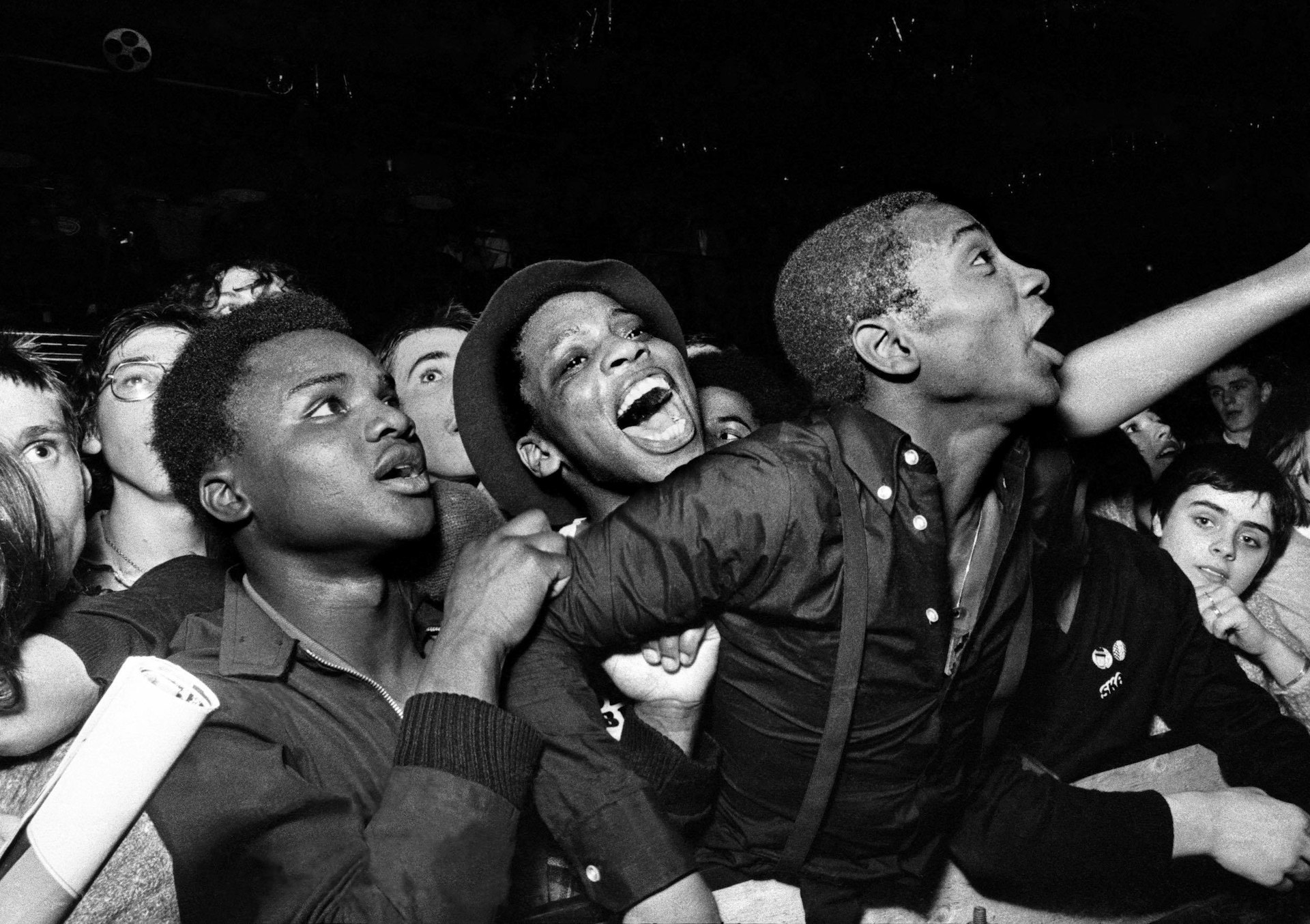

Rock Against Racism was one of the most successful social movements of the 1970s. Taking a stand against the surge of race hate infecting a disillusioned Britain, a meeting of bands, artists, writers, photographers and the like came together to fight for diversity and racial unity through staging gigs that boasted diverse bills and a spirit like no other.

Syd Shelton was the de facto photographer of Rock Against Racism, capturing the spirit of the movement with evocative and powerful black and white images. As we approach the moment’s thirtieth anniversary of the movement, Shelton’s iconic images are to be published in a book Rock Against Racism and exhibited at London’s Autograph ABP gallery.

Sparked in turn by rising support for the National Front and a speech by Eric Clapton in which he derided foreigners and said he wanted to “keep Britain white”, Rock Against Racism emerged in 1976 to put on gigs and counter demonstrations by the National Front in multi-racial areas of London such as Wood Green and New Cross. Syd joined in 1977 and became part of what he describes as an “anarchic meet-and-greet of people”.

Paul-Simonon of The Clash at RAR Carnival, Victoria Park, London 1978.

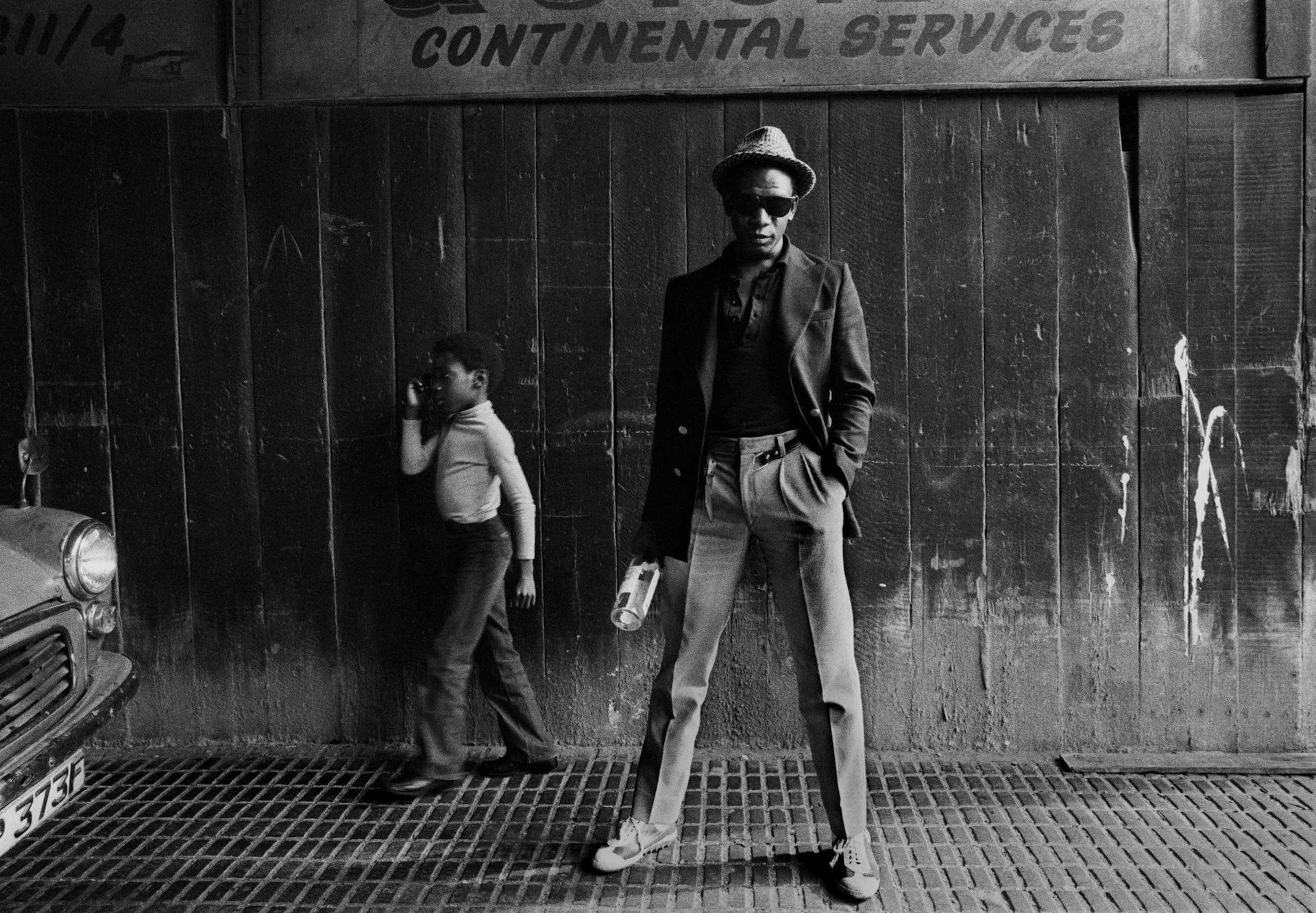

Syd wanted to capture the whole picture. “I come from that tradition of the street photographer, mixed with portraiture,” he explains. “You are looking for visual clues which can construct a whole idea, and that’s how I’ve always approached photography.” He says that you cannot be an objective impartial observer, but should strive to be somebody who can get to the heart of their subject matter – an idea he epitomised through his role as both photographer and preeminent member of Rock Against Racism.

The group started staging shows at small venues putting on an eclectic range of punk and reggae bands, such as Aswad, Misty in Roots and Sham 69 as a giant middle finger to racists. “It was a fantastic celebration of diversity, but also a celebration of something new, and that was punk rock as well.” Alongside musicians, RAR’s collective of artists, photographers and designers also put out a fanzine called Temporary Hoarding, which folded out from an A4 zine into an A1 poster. “The central poster was always a thing that we got excited about producing because we thought that was the thing that would live on,” Syd recalls.

Bagga, vocalist with Matumbi, Hackney, London, 1978.

A particular march in Lewisham, on 13 August 1977, sticks in Syd’s mind: the National Front decided to stage an ‘anti-mugging’ march in Lewisham to ‘whip up the ante’. “At the time, if you were young, black, and male in particular, then you were really caricatured as a mugger,” he remembers. “It was a little bit like the nonsensical thing that sees all Muslim people as Jihadists. It’s the same sort of caricature and it was really horrific.”

“We were all involved as Rock Against Racism and as individuals in organising a counter-demonstration, which was a fantastic mixture of local people and political activists from all over the country,” Syd says. “It was around 5-10,000 people against these 125 National Front marchers.” The ‘Battle of Lewisham’, as it came to be known, was the first use of police riot shields in mainland Britain, something Shelton describes as “the militarisation of the British police”.

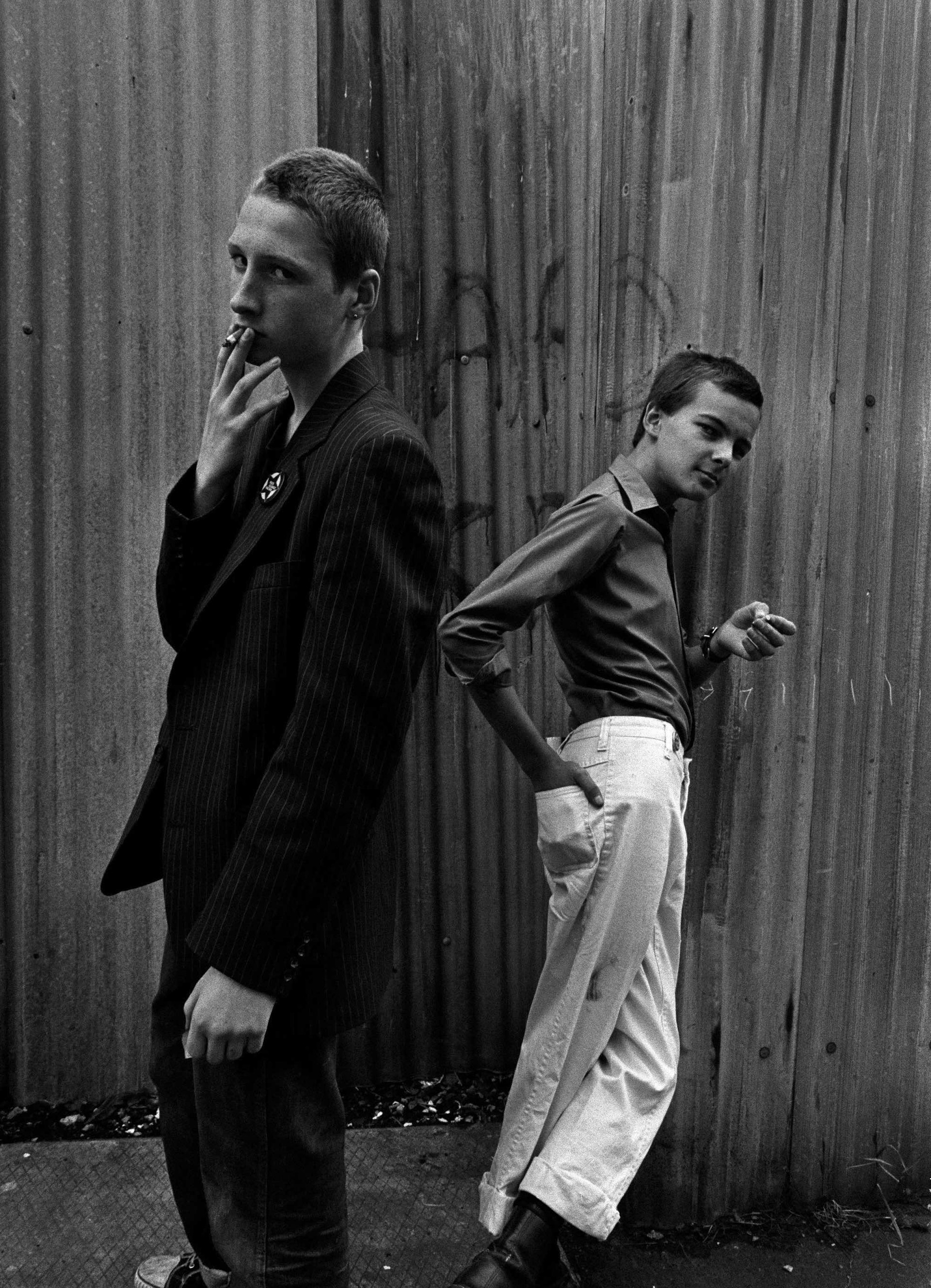

Anti-racist Skinheads, Hoxton, London 1978.

The movement really took off when they started to march in central London, notably the tens of thousands that walked from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park on April 30 1978. Bands such as The Clash and the Tom Robinson Band were scheduled to play in the park, and the organisers could never have anticipated how it would catch on.

Could he ever forsee this? “We were too close to it to anticipate how big it was going to be,” he says. “I guess in the same sort of way a famous person often doesn’t even know what it means to be famous, and they’re quite shocked when somebody recognises them.”

A few months later, Rock Against Racism staged a large gig in Brockwell Park. Although Sham 69 were scheduled to play, they pulled out due to murder threats from racist fans aimed at lead singer Jimmy Pursey. However, a kid in the street talked to Pursey the night before Brockwell Park. “This young kid came up to him and went ‘ah Jimmy, you’re not doing the carnival because you’ve got no balls’, and apparently it worked on his head all night and he really got worried.”

Yet on the day of the Brockwell Park gig, Pursey made an unexpected appearance. “Jimmy had his backstage pass, burst in, went past me straight to the front of the stage, grabbed the microphone and made the most fantastic speech telling the story about the young kid,” Syd remembers. “He also said that he’d come there because he supported Rock Against Racism and that he hated the racist fans that had adopted him. He was incredibly brave to do that – he was shaking. In fact I was shaking taking the photograph!”

“That was an incredibly emotional high point in a way for Rock Against Racism,” Shelton adds. The movement continued staging gigs around the country for the next few years until 1981, when they felt it was time to pass the baton along to the next generation. The photographer describes it as a “fantastic party that we went to for five years”.

However, Shelton says modern incarnations of Rock Against Racism “didn’t get it”, such as Love Music, Hate Racism, which was set up in 2002 and has staged gigs with acts such as The Libertines and Ms. Dynamite. “They were all about sloganeering, which is not what we put in the arguments. We saw that the idea of Misty jamming with the Ruts or the Clash was in itself a political statement. It didn’t need those simplistic slogans in between.”

Although they felt like they changed things there are inevitably still problems, not least in the response to the current refugee crisis. Syd is particularly shocked by the British government’s quota of taking in 20,000 refugees over the next five years. “Melanie Phillips wrote in The Times the other day that refugees would change the culture in this country,” he says. “Good! Let’s change the culture of this country, that’s what we want to do. That’s what Rock Against Racism wanted to do.”

With his new exhibition and book, Syd’s five years at the forefront of one of the biggest social movements of the 1970s are captured in all their glory. “It was hard work and we never made any money – we never did it to make money,” he reflects. “We didn’t have time and were always skint! It was phenomenally empowering – that was the most important thing. We felt as though we could change things, and I think we did.”

To sum it all up, Syd ends with a quote from the late writer David Widgery, who was another driver of Rock Against Racism: “It was great at being political without stopping the party.”

Rock Against Racism: The Exhibition shows at Autograph ABP Gallery, Rivington Place, London EC2A 3BA, October 2 – December 5 2015. Admission: Free.

Rock Against Racism: The Book is published on October 1 2015 by Autograph ABP.