A glimpse inside California’s Romani communities

- Text by Isaac Muk

- Photography by Cristina Salvador Klenz

When Cristina Salvador Klenz, then aged 20, was on summer holidays from her studies as a photojournalism student at the University of Missouri, she took a visit to Portugal. It was where her grandmother lived and her parents had migrated to the USA from and, it being the first time Klenz had visited without her parents, she was keen to explore.

One day Klenz and her grandmother decided to take a road trip to the north of the country and drove towards Braga, when they saw a cluster of families living by the side of the road.

“Who are these people?” she asked her grandmother.

“They’re Ciganos,” her grandmother replied, using the local pejorative for Romani people, a historically nomadic cultural and ethnic people found around the world, who often live in camps like the one Klenz saw that day.

Intrigued by their makeshift homes, she asked to pull the car over and walked over to greet and photograph the families in the encampment with their permission. “I was devastated by the living conditions,” Klenz says. “They were living in shacks, they didn’t have any plumbing or electricity, blankets were strewn over the dirt floor. [But] the children were beautiful and amazing – they were radiant, and they greeted me with open arms.”

She would return to the camp throughout the summer, and the people she met caught her interest so much, that upon returning to the USA, she decided to seek out Romani people in her home state of California.

Klenz’s new photo book, Hidden: Life with California’s Roma Families, is a collection of her photographs taken between 1990 and 2003 – of the people she met and befriended who invited her into their homes. Her shots are an intimate look into the cultures, diversity and living conditions of Romani people in the Golden State, who often reside in the towns and cities of the typical American but exist mostly outside of mainstream society.

Their housing situations mostly differ to their counterparts in Europe, with large families residing predominantly in rented accommodation, rather than camps. It renders their existence almost invisible, tucked away in American houses and apartments rather than on roadsides.

Many are also reluctant to send their children to school. “A lot of the Roma in Europe [historically] were not allowed to settle,” explains Klenz. “European countries had laws that forbade them from settling so they didn’t put their kids into school.

“Most of the parents were illiterate – they couldn’t write their names” she says. “That was one of the most tragic things about the culture, because it’s very difficult to advance or to fill out any documentation and get the help that they need, when they have very few members who can read or write.”

Their separation comes partly as a protective measure. The Roma have historically faced widespread discrimination, and a 2020 Harvard survey found that 70 per cent of Romani Americans “hide their Romani identity to avoid being stigmatised, stereotyped and discriminated against”.

One woman named Povlena, who Klenz photographed, told her: “People treat us like we’re some type of monsters, and we always get dirty looks. People whisper to one another about us and don’t like us period. [They say] ‘hide your kids, money and valuables – here come the gypsies.’”

Despite these hardships and abuse, the Roma subjects of Klenz’s photographs are brimming with humanity, showcasing an intimate and defiant side to Romani culture and life. Familial bonds are particularly tight knit and despite mistrust of outsiders, Klenz was made to feel welcome.

She was even allowed to photograph the birth of a child – a taboo in Roma cultures – and spent three weeks living with the expecting mother’s family. “They took me in almost as a member,” says Klenz. “They were very accommodating and protective of me – putting me in bedrooms with the children where I would sleep. It was an amazing experience.

“Romani people will tell you: ‘We live for our children.’ Children go everywhere with them,” she continues. “As a society as a whole, if we could take that aspect and treat children in the same manner – our humanity would be better, and our children would be better off.”

Hidden: Life with Califoria’s Roma Families is published by Brown Paper Press.

Follow Isaac Muk on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

You might like

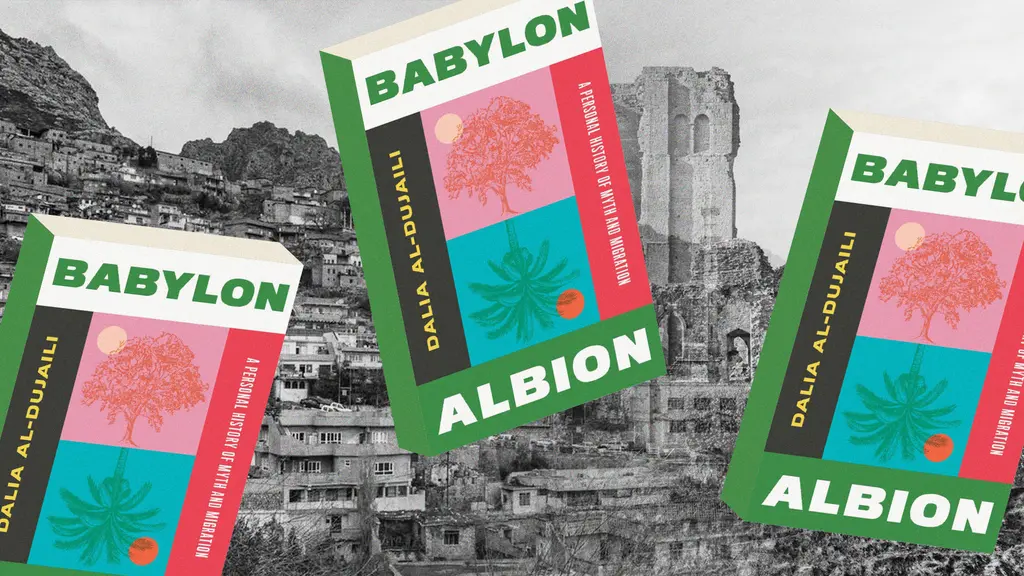

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro