Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

- Text by Zahra Onsori

- Illustrations by Han Nightingale

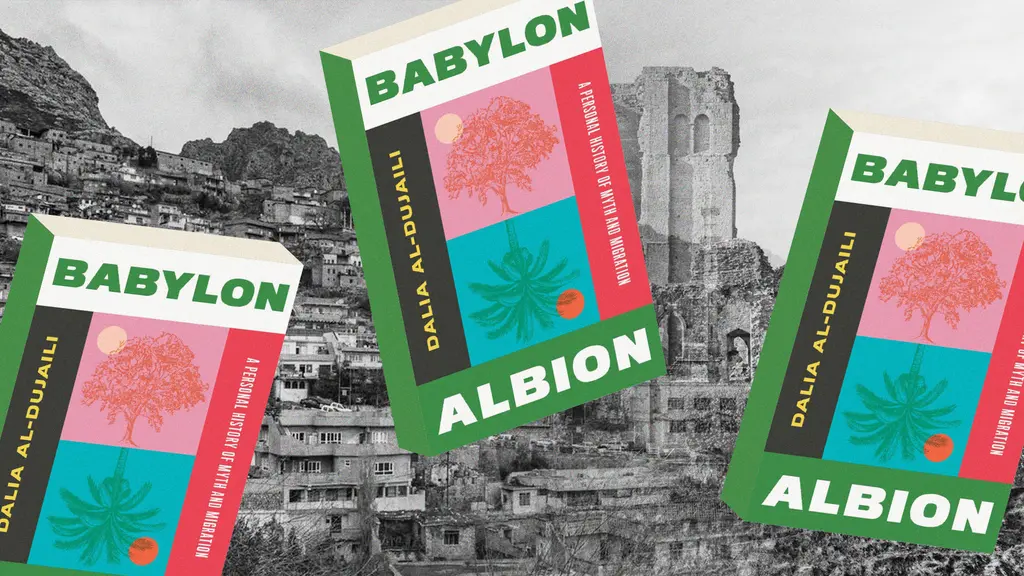

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Before our identities were confined to tick boxes on D&I forms and cartography borders, we were all people of the earth. Humans and the land were one; tied up in folk songs, the quiet knowing of what blooms when, of the husk in the air before it rained. The land wasn’t just a place where we lived – it was who we were.

But things are different now. Colonial legacies, the hunger to control the wild, the slow erasure of memory and languages. The land is wounded. But somehow, nature keeps reaching out. The shade of an oak tree on a hot day. Cooling off in the ocean, bare feet squelching in the sand. No code-switching, no confusion, no conditional love – you can just be. This is a feeling that Dalia Al-Dujaili found herself drawn to her whole life.

Born to Iraqi parents and raised on British soil, Dalia’s relationship with identity and home is a fragmented one – a feeling shared by many second-generation immigrants who yearn to feel at home. It’s partly this experience that led Dalia to become a storyteller, with an interest in telling stories about communities in the margins. For the author, home is the land. Whether it be the scent memory of earthy clay and jasmine, or the stories and scriptures about the Iraqi date palm, nature has always been a place where she can belong.

Her debut book, Babylon, Albion, is an exploration of that identity. Through a mixture of poetry, as well as deep dives into ancient mythology and religious scripture, she takes us on a journey through her life as she navigates her British upbringing and Iraqi heritage. It sets out to answer why she feels so at home in the natural world, and how nature can be a healing force in times of disparity, for all of us. We spoke to Dalia from her blooming garden in Surrey, where she sat shaded under a mature flowering tree – a fitting backdrop for our conversation.

What sparked the idea for the book?

The book was motivated by my entire experience of being who I am, growing up where I’ve grown up, and having a multiplicity of identities. I wrote it because I wanted to explore that question for myself: “What is my identity?” and why I feel such a draw to the natural world. One experience that inspired me to start writing the book was with a group called The Visionaries, which is run by a wonderful guy called Max Girardeau. He took young leaders camping in the Lake District, and it was one of the most healing and inspiring things I’ve ever done in my life. After I came back from that trip, I had a lot of thoughts, feelings and emotions, and I just felt like writing it all down. So I started writing. Babylon, Albion actually started as a photo collage. I’m a very visual person. I’m a writer at heart, but I’m also an editor of photography, visual culture and art. The cover of the book was one of the first collages that I made. It was an oak tree and a palm tree. I cut them in half and stitched them together, and then I started making all these digital collages out of images. I would look at the images and just let the words come to me. Poems I’ve read, poems that I’ve grown up with, hymns, prayers, art. It was quite a spiritual process at first.

The book draws on a lot of themes that tie nature in with your life. What does nature mean to you?

It’s my life. I think nature is God, in the sense that nature creates everything, and nature is life. In terms of nature and how it relates to my identity as a second-generation immigrant, it’s the question this book is asking, one that I don’t really have an answer to. As a second-generation immigrant, to put it plainly, I feel like the natural world is the most pure place that I can relate to because I am a placeless person. Most diaspora feel that way, in the sense that they don’t call a single place home. When you are placeless, I feel like nature can fill that void for you. And because nature and land is universal, it’s a shared home. I feel a sense of deep belonging when I’m out in nature, especially in the UK. I feel most at home when I’m walking outside, whether it be in the park, or under a tree. I’m looking at a tree right now, and I feel so much more deeply connected to this tree here in Britain than I do to any sense of the British flag or the National Anthem, or stories that we got told about colonialism. I didn’t grow up in Iraq, so I find it quite hard to relate to nationalistic ideas and symbols and narratives, but I feel super connected to sand and palm trees and the rivers and songs and myths about them. So yeah, nature is a home, I think, for all of us.

Symbols of resistance and national pride for diaspora communities are often tied up with nature. Why do you think that is?

I had a really amazing conversation with Layla Feghali, who I quote a lot throughout the book. She’s written an incredible book called The Land in our Bones, where she calls plants her ‘plantcestors’. They are our plant ancestors, and essentially, if we follow Layla’s line of thinking, plants are symbols of resistance, because plants are our ancestors and are the origin of all of our founding myths, our folklore and our history. Plants are the root – pardon the pun – of our identity. In my book, I talk about the date and the date palm a lot. This is how Iraqis identify themselves, because the palm tree is so core to how the land shapes us. That’s why I wanted to open the chapter of the book with the oak and the date palm. I learned a lot from Layla and her book and her work. She does incredible work. There are so many brilliant, talented, equipped guides in this space that are more knowledgeable than me. I love Layla’s way of thinking.

Navigating a second-generation identity is a complicated thing, and it can be difficult to tether down this idea of belonging. What sort of lessons can we learn from the natural world when it comes to our identity?

If we look at the natural world, we find that we are trying to fight nature by trying to fit ourselves into the mould that a colonial world has created and forced on us. And identity is not that simple, and neither is nature. There’s a great quote in the introduction to the book, Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd, which describes the mountain: “Thrilled by the alterity of the Cairngorm granite, by a mountain-world which ‘does nothing, absolutely nothing, but be itself’.” There’s no point in trying to imagine a mountain wanting to identify as a hill. It’s a mountain. And there’s nothing you can do about that. You can’t shape-shift it and force it into something that it’s simply not. It’s beautiful and powerful in the way that it is. Like the mountain, my identity is beautiful and powerful just the way it is. I don’t need to go either this way or that way. I can just be who I am in my wholeness.

“As a second-generation immigrant, to put it plainly, I feel like the natural world is the most pure place that I can relate to because I am a placeless person. Most diaspora feel that way, in the sense that they don't call a single place home.” Dalia al-Dujaili

In the book, you explore the fact that people intellectualise nature. One of the quotes that stood out to me was ‘the more we understand, the more we seem to lose’.

This is an idea that’s taken a lot of inspiration from other people, which is important to state. They are ideas that everyone’s had before me, but I’ve accumulated them in one place from my perspective. When I’m talking about conservation and ecology, that’s not me protecting nature. I am protecting myself, because without the wildflowers and the bees, I die along with my kin. As a diaspora, we don’t necessarily have the same relationship with British land and British countryside compared to English people who have been here for generations. I’m looking at loads of plants right now. I can’t name a single one of them. I think maybe that’s rosemary because it looks like rosemary. I need to go and smell it to check. But I don’t know what any of these plants are. You don’t need to know anything about nature to respect it, to love it, to care for it, to be a steward of the planet. You don’t need to understand things from an intellectual or scientific point of view to feel deeply connected to it. I’m a big advocate of enhancing our scientific ventures, but the more science we apply, I feel like we end up putting out a lot of the human connection to the natural world.

You are Iraqi but were born and raised in the UK. What helps you feel connected to your heritage?

I’m writing the book from the perspective of someone who’s lived their whole life in the UK and who’s travelled to the Middle East a lot, but never lived there. That’s where, for me, the deep discomfort comes from. The disconnect is that I feel such a connection to the land of Iraq. The land lives through my family. And that’s why I centre my mother and family a lot in this book, and how they brought the land with them. When I talk about my Mum, she didn’t intend to pack the land in her suitcase when she got on that plane, but she did, because the land does not ask to be a part of us. It already is.

The land lives through my mother. I feel like I inherited that land through my family. I feel deeply connected to Iraq, because of my family and what I’ve inherited from them. When they talk, I see the land come alive in front of my eyes. They talk about staying up on the roof and watching the sun come up and having to run away from the heat of the day, and the fruit carts that would go through the streets of the city of Dujail and Baghdad. This is why I dedicate the book to my mom and dad, who are my living landscapes of love and memory. I did spend quite some time in Jordan, Amman, as a kid. A lot of Iraqi refugees live in Amman, a lot of my family included. That’s where I would go, because it was never safe to go back to Iraq. I spent a lot of the summers of my childhood in Amman, and that was the closest I could get. The land is kind of similar to Iraq, but very different in a lot of ways. I spent some time there while I was writing, and that was good. It wasn’t even so much about being in a place that looks like Iraq. It was more that I was with family, and that’s what made me feel connected to what I was writing about in the book.

I think it’s interesting that you talk about the discomfort that comes from feeling so connected to somewhere, yet not kind of knowing it at all. When writing this book, did it force you to confront any of those discomforts?

Absolutely. Did I overcome them? That’s still an ongoing journey. The journey of self-acceptance, no matter who you are, is universal. You don’t have to be part of a diaspora to feel like you haven’t accepted your self-belief. Writing the book did allow me to confront a lot of discomfort about how distant I am from Iraq, but I’m not resentful of that. I’m so thrilled that I got to grow up in the UK. I love being from here. I really love this place. I don’t love the idea of Britain so much, but I love British land. I love the trees here. I love the grass. I love the hills. I love the forests and the lakes and the rivers. I just love British land. I think the most discomfort comes from feeling an unavoidable hole in oneself. I have a yearning that I don’t think I will ever really fulfill, which is the yearning for the land of my motherland and my fatherland. I will never fill that hole, so I have to find a way to make peace with that. And the book is an attempt at that, but it’s not the final answer.

You dedicate the book to your mom and dad, what’s their reaction been?

They haven’t read the book yet, but they already love it. Their daughter wrote a book, so for them, they’re like: “Our job is done.” I come from a humbly long lineage of authors, journalists and artists, my grandmother included. I was going to say that I think they’re really proud of me, but actually, I’m really proud of them because of the way they raised me. Every immigrant or kid of an immigrant feels this way. Your parents left their home and went to some random place. They settled and built a life and made it the best life that they could possibly have. They made do with what they had, and my parents did an incredible job of what they had. It feels weird to say that you’re proud of your parents, but I genuinely am. I’m so humbled by their strengths, their patience and dedication and their drive, and I will never have that. I’m very proud of the people that they are and that they became when they travelled to this place. They taught me a lot about loving where you’re from, but also loving where you are as well.

Babylon, Albion by Dalia al-Dujaili is published by Saqi Books.

Zahra Onsori is a freelance journalist. Follow her on Instagram.

Buy your copy of Huck 81 here.

Enjoyed this article? Follow Huck on Instagram and sign up to our newsletter for more from the cutting edge of sport, music and counterculture.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.

You might like

Three heart wrenching poems from Gaza

Writings that narrate — With Gaza’s population facing starvation, we are handing over our website to Yahya Alhamarna, a displaced poet and student in Gaza, who shares some of his recent poetry, and explains why writing is so important to him.

Written by: Yahya Alhamarna

An insider’s view of California’s outdoor cruising spots

Outside Sex — Daniel Case’s new photobook explores the public gay sex scene, through a voyeuristic lens, often hidden just below plain sight.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Daido Moriyama’s first four photobooks to be published in English for the first time

Quartet — A new anthology collates Japan, A Photo Theater, A Hunter, Farewell Photography and Light and Shadow, alongside journal entries and memoranda.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Meet Lady Pink, the ‘First Lady’ of graffiti

Miss Subway NYC — As a leading writer and artist in a man’s world, Sandra Fabara has long been a trailblazer for girls in underground art. Now, her new show touches on her legacy, while looking to the future.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The Tossers: Inside the world of competitive egg throwing

The Obsessives — From Russian Egg Roulette to the showpiece Throw and Catch, the World Egg Throwing Championships is a cracking tournament. Ginnia Cheng joined this year’s edition, and scrambled to keep up.

Written by: Ginnia Cheng

Ari Marcopoulos

A Pretty Loud Fly — Ari Marcopoulos isn’t a photographer. He’s an astronaut, a transplant, a man on a mission to expose the world, who in so doing leaves himself exposed.

Written by: Shelley Jones