A visual ode to Hungary’s declining pub culture

- Text by Isaac Muk

- Photography by Zsófia Sivák

In 2011, when Zsófia Sivák was 18, she moved from a small village in eastern Hungary to the country’s capital and biggest city, Budapest. She was to attend the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in order to pursue her dream of becoming a photographer. It should have been an exciting time, studying photography and living in the traditional centre of the country’s arts and culture scenes, as well as having countless young, like-minded people surrounding her.

But what she found, similarly to many others who migrate from rural to urban areas, was that the big city was not so friendly. “It was a really difficult period – turbulent and emotional,” Sívak says. “Because in the university, most people were from a different social class and they were different to people in my hometown.”

Having spent most of her youth thinking about leaving her village and dreaming of the bright lights of the big city, during this time she found herself doing the opposite – yearning for home. Sívak had always used her camera to document her surroundings and understand her identity, and she started being drawn to making pictures of rural Hungarian life.

“It was a therapeutic process for me,” she says. “Circling around my identity, finding out who I really am.”

One aspect of village life Sívak found herself drawn towards was the rural Hungarian pub. As boisterous, social places with flowing beer and loud chatter that her father used to take her to when she was a child, she associated pubs with fun and community. Naturally, she decided to begin a photographic project documenting the taverns and pubs of her home region.

But what she found was a culture in decline, with many pubs struggling to make ends meet. As people struggle financially in rural areas, as well as a large trend towards people leaving for cities, she found taverns closing down or often populated with very few customers. Her ongoing series Our Prices are in Forints documents the fall off of the tavern culture, and the last bastions of the rural Hungarian pub.

“At first I thought pubs were happy places, with people drinking and dancing,” Sívak explains. “But once I started to go, I realised that no one goes to pubs anymore, and just some old people sitting around tables.”

As one of the few places in rural areas people would gather to socialise, the taverns have historically played an important part in Hungarian society. The photographs capture the unique beauty of the establishments, with simple designs and pastel furnishings, as well as the people who keep the tradition and spirit alive – the landlords and few remaining patrons.

Their fall in popularity is a story as much about poverty in the Hungarian countryside as about a decline of a culture. “People have less and less money, even for their basic needs,” Sívak says. “They don’t go to the bar at the end of the month because they don’t have money to pay for the beer, which is shocking because one beer costs around half a Euro.”

The pictures reflect this: a number of the shots are of empty venues, and when people do appear, there are rarely more than one or two subjects. This was despite the fact that Sívak usually only travelled to the rural pubs during the busier periods at the beginning of the month, when people have recently been paid and therefore have more money to spend on beer.

Many landlords she met believed that they would be the last ones of their taverns. “The pub owners are worried about closing,” she says. “These are family business, and young people just don’t want to care for them anymore.”

But on the other side of the bar among customers, Sívak heard a different story. “It seems like they don’t worry that much,” she says. “Because it’s a process in society – these places just dismantle over time and they disappear. It’s not something they can react to, they just accept how these processes happen.

“Rural places are becoming poorer, the money is disappearing” she continues. “It creates more distance between people and the social classes – there will only be an abandonment of these places.”

Follow Zsófia Sivák on Instagram.

Follow Isaac Muk on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Follow Huck on Twitter and Instagram.

You might like

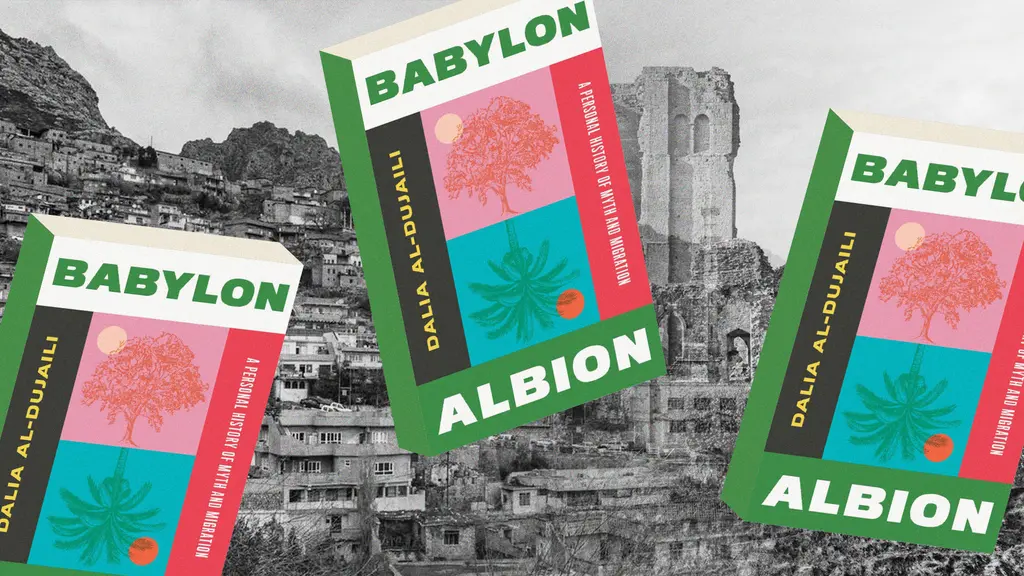

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro