The American dream is finished: Bruce Gilden in Detroit

- Text by Alex King

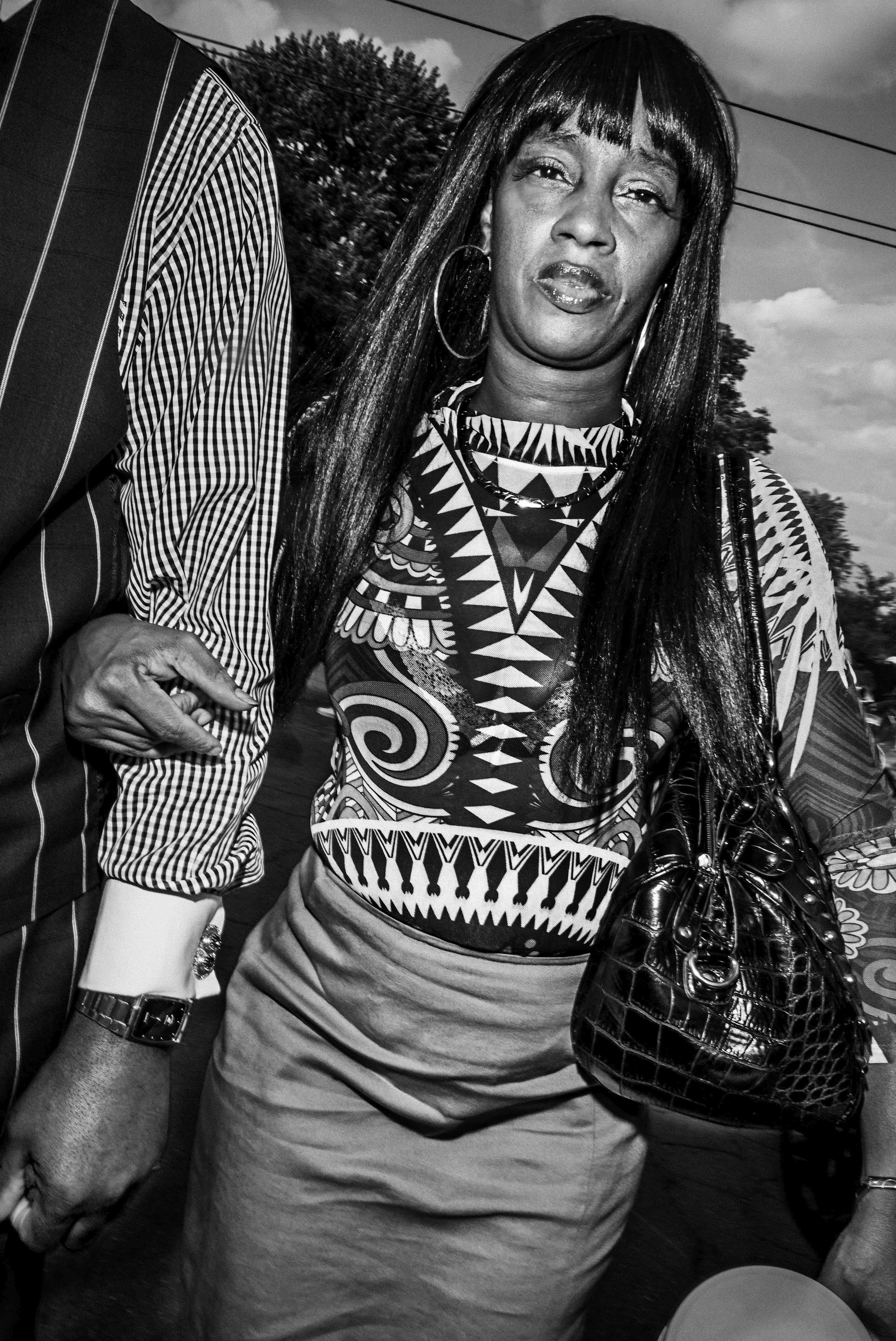

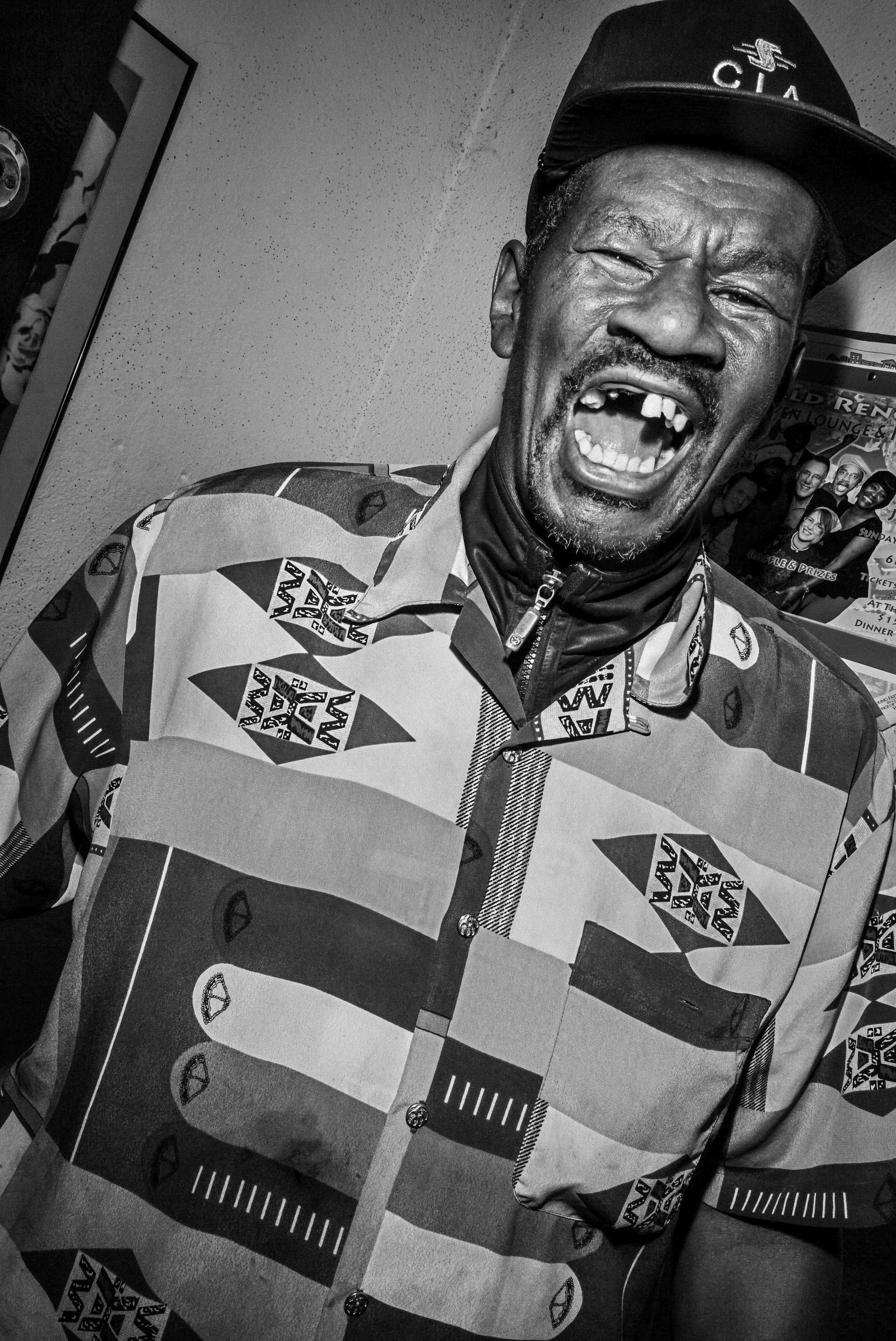

- Photography by Bruce Gilden / Magnum Photos

Houses in Detroit go for a dollar these days. It’s a sign of how hard the once mighty Motor City has fallen.

In its heyday, if you hit the road in search of the American Dream, all signs pointed towards Detroit. It was once a temple to American capitalism: the throbbing heart of the automobile industry, where the blue collar man could command a higher wage than anywhere else in the country.

Detroit’s fall from grace has been well-documented. The city has lost over a million souls, from its peak of 1.8 million. Today, the 700,000 people who still call the city home have had to grit their teeth and survive amidst the highest rate of home foreclosures, the highest unemployment and the worst performing education system in the country. Detroit has also held the infamous title of national murder capital for much of the last decade.

Magnum street photographer Bruce Gilden arrived in Detroit in 2009, while documenting the effects of home foreclosures across America after the sub-prime mortgage bubble burst. He was surprised by the apocalyptic scale of devastation he witnessed – but impressed by the tenacity of the city’s people and their never-say-die attitude.

“Today Detroit is still a very special city,” he explains. “I’m inspired by the beauty in this apocalyptic place, a place that not only breeds violence but also poor education and poverty. It’s a great city that suffers and yet has kept its soul. Detroit’s inhabitants, in their own ways, don’t give up.”

It was this spirit that drew him back, and in 2016 he returned to shoot Detroit: Against The Wind.

Born in Brooklyn in 1946, Gilden first found fame as a street photographer with his series on the pleasure-seekers at New York’s Coney Island. Since the 1980s, he has carved out an instantly recognisable style through his confrontational approach and use of flash in striking black and white images. He has since criss-crossed the Five Boroughs, travelled abroad to Haiti, Russia, Romania and elsewhere, to shoot biker gangs, prostitutes and Japan’s yakuza mobsters.

But Detroit, he says, is one of his favourite places. “I’d go back again anytime.”

What struck you when you first arrived in Detroit?

I first went to Detroit in 2009 for my book No Place Like Home: Foreclosure In America. I had never seen anything like Detroit in my life. It was like an apocalypse. The houses there were unbelievable because they used to have the highest wages in America for blue collar workers, so the houses were like grand dames who had seen their best days. I was on a block with 70 homes, 63 of which had been foreclosed and some were half standing, there were no streetlights. It was just an amazing sight. I couldn’t believe that this was America in 2009.

Could you talk about finding affinity with the people you met who you said ‘had seen better days?

For me, people who have seen better days are, in some cases, artistic people. They gave their life to their art and never had a lot of success monetarily. And that doesn’t always mean they’re bad singers or they’re bad painters or they’re bad photographers. For whatever reason, whether it’s they just met the wrong people, they took the wrong turns, or whatever reason, they were too obstinate.

I like people like that because they took a chance and they lived their dream. It’s OK to live your dream, as long as you have enough talent to live your dream. People who fool themselves and think they’re good artists and they’re not, then they’re suckers. But the people who are good… you can go into a Blues club in Detroit and hear people that are pretty good and they struggle to make a living but they’ve still got that soul, they’re still singing and they got something that money can’t buy.

I enjoy being around that, I enjoy being there, and that’s what you find in Detroit. If they wanna tell you something, they tell you. If they want to tell you to go fuck yourself, they tell you to go fuck yourself. I don’t like this passive aggressive or P.C. world. I’m not a P.C. person, if I’ve got something to say to you, I’ll say it.

Does the American Dream still exist in Detroit? Did it ever exist?

Detroit was a fulfilment of the American Dream. You could not be well educated, you could be a blue collar person and you could have a nice standard of living, until everything collapsed. But yes, the American Dream doesn’t exist.

Of course you find people who will make it, and I’m not talking about athletes, I’m not talking about singers or very smart people who do start up companies, or whatever. But for the average person, it’s tough. Look, years ago you could have mom and pop shops, now they all go out of business because you have all the huge conglomerates. How can you compete with them? I think the American dream is finished. I don’t think it’s going to come back.

Is Detroit today a dystopia?

Hold on a second, I’ve got to ask my intern because he goes to Vassar. [He leans away from the phone] Could I call Detroit a dystopia? [There’s a reply I can’t make out] He’s more intellectual than me, he said you can call anywhere a dystopia if you look hard enough. I wouldn’t use that language because that’s not a word I would use, OK? I could say that it looks like the apocalypse hit there in certain areas.

Did shooting in that type of environment affect you in any way?

The numbers [of empty lots and houses] are numbing. We drove round looking for people every day for eight hours, we would turn around again and again and see the same things over and over again. It’s like going on a merry-go-round in a bad area and it starts to affect you.

It’s infectious. What I mean by infectious is that it numbs you, there’s nobody around, you see a lot of decrepit stuff and it starts to wear on you. You start to get annoyed a little bit. Because at the end of the day, there’s almost so much there that the people can’t ward of all the elements that are coming at them.

Did you see people working to improve the situation?

Every now and again you’ll have a block that’s kept up well, it’s clean and there’s a neighbourhood watch. But on some of the emptier blocks, there’s not a lot of people out and you know danger looms. Something can happen there.

Believe me, I’m not a humanitarian. Or rather, I am, but I’m not a humanitarian in my photography. And I think I’m a pretty smart individual, very very street wise. I grew up in a bad area and I had to make it all on my own. So I am knowledgeable about these situations, that’s why I’m also close to this.

I grew up with the stray dogs, I grew up with the guy sleeping on the stoop drunk at night. I grew up with the people that had nowhere to live. So, it was part of me until I was eight. I saw it on the way coming home from school. So I identify with all of this. But I’m also tough on this. Because I think if you want, you can make your way out of that. You just have to have a lot of intestinal fortitude, which I have.

Bruce Gilden’s Detroit: Against The Wind was commissioned by Leica and is on display at Leica Gallery Mayfair, 17 September – 6 October 2016.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.