How austerity targeted... Northern cities

- Text by Alex Niven

- Illustrations by Terrence Hardcastle

In 2015 I returned to the North-East of England after a decade away to find it cracked and faded like an old sepia print. Like almost everywhere else in modern Britain – especially places on the fringes of the islands – the region was struggling under the weight of years of austerity. The North-East had become the target of a calculated strategy of political and economic neglect, which was both profoundly depressing and acutely angering.

Like the vast majority of my friends, I moved down south for university and then work in the early noughties. This was a slightly less dreary time for the region. Though the years which brought us the Iraq War, foundation hospitals and tuition fees can scarcely be described as a golden age, under New Labour there was a sense that things were getting very slightly better, on the surface at least.

Newcastle and Middlesbrough were treated to shiny new art galleries (the Baltic and mima) in the first years of the 21st century. Meanwhile, the buoyancy of the economy pre-2008 meant that public services were still holding their own, for all the ruinous effects of privatisation.

Next to nothing had been done to reverse Thatcher’s liquidation of smaller coalfield towns like Ashington and Easington back in the eighties, and unemployment in general remained high. But if you visited Newcastle’s revamped quayside or listened to one of the region’s crossover art-rock bands circa 2006, it was just about possible to believe the tourist-board cliché that this part of the world was ‘buzzin’.

But returning to the region in the middle of a long decade of austerity was like the first section of Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, where Kevin Costner’s exiled protagonist arrives back in Nottingham to find his home in ruins and an evil sheriff exploiting the starving populace.

With its sharp civic design and unusually friendly people, Newcastle has the potential to be one of the finest cities in the world – a boisterous, modernistic European port stranded on the edge of weary, nostalgic England. But underneath its proud exterior, by the mid 2010s there was unmistakable evidence of widespread decay.

The signs of economic collapse were by turns obvious and subtle. If you walk around the centre of Newcastle today, you will see a fair amount of new development oriented around the transient hedonism of the student and night-time economies – private student apartment blocks wedged awkwardly on the edge of Georgian terraces, plastic-clad hotels catering to the stag and hen-do market, cavernous chain bars festooned with fake topiary offering 4,563 diverse varieties of botanical gin.

But beyond the Hogarthian indulgence of the weekend and term-time blowout, Newcastle is literally rotting. The Bigg Market – a celebrated nightlife area in the centre of town – is full of gutted ex-bars. Tragically and symbolically, one of these is legendary Victorian music hall Balmbras, which plays a starring role in the regional folk anthem ‘Blaydon Races’.

The Georgian and Victorian heart of Newcastle is easily on a par architecturally with anything in Bath or Brighton. But while many southern towns have retained their status as affluent commuting and tourist hubs over the last decade, the continued lack of employment and investment in Newcastle has left parts of it looking like Bath abandoned in wartime. Exquisite neo-classical arcades now house empty shops, and the roofs of elegant townhouses are strewn with meadows of weeds.

The deeper context for all this is of course the failure of successive governments since the post-war years to find a viable replacement for the region’s reliance on core industries like mining and shipbuilding. Times change, and no one wants to return to the carbon-heavy, emphysema-ridden days of the industrial past. But an alternative long-term plan for the region has played almost no part in the political narrative since Thatcher.

As governments deliberately shifted the focus of the economy to London and its finance and service industries, the gap left by the evaporation of heavy industry in the North-East was only mitigated with palliative measures – a fragile welfare system, periodic government endowments for ‘regeneration’ schemes, capricious handouts for cultural projects.

Now even these partial and temporary band-aids have been ripped away. It’s one thing to reel off cold statistics to illustrate austerity’s impact, like the fact that Newcastle City Council will have suffered total cuts of £327 million between 2010 and 2022. It’s quite another to walk down the city’s main shopping thoroughfare Northumberland Street, and see multiple homeless people crouching under the hoardings of chain stores and fast-food outlets.

We didn’t have any corporate coffee bars or mobile phone retailers in the North-East when I was kid. But we didn’t have any foodbanks either, and I don’t remember there being any homeless people on Northumberland Street. Dealing with this disjunction between past and present, and having to accept that my hometown has markedly declined during the course of my lifetime, is one of the hardest things I have ever had to bear.

Alex Niven’s book, New Model Island: How to Build a Radical Culture Beyond the Idea of England, is available now from Repeater. Follow him on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

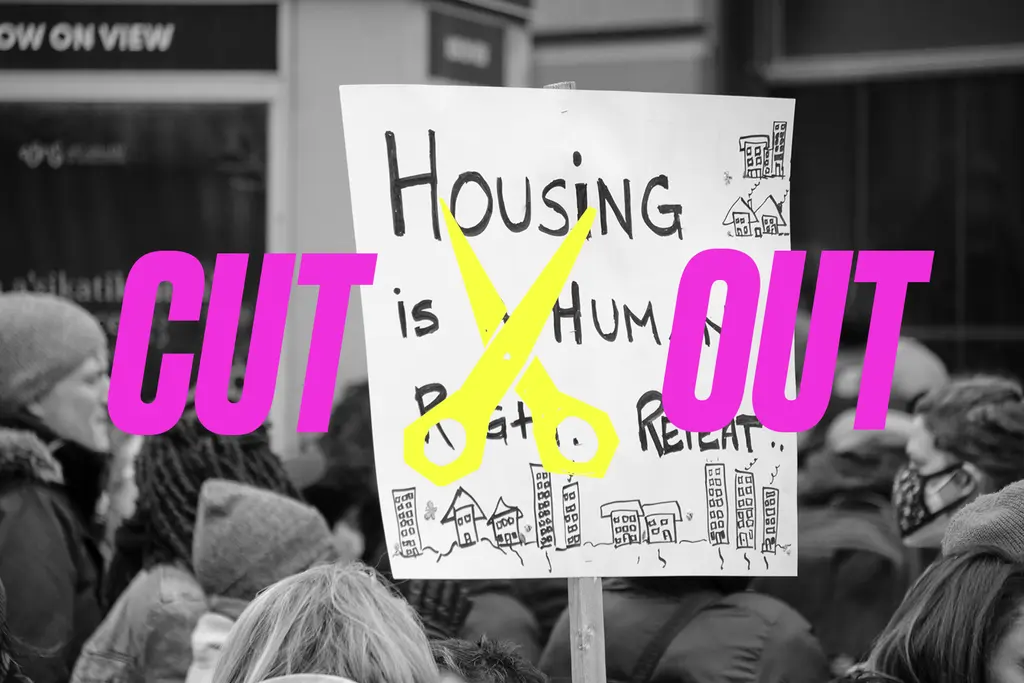

How activists have fought back against the escalating housing crisis

The last five years have seen astronomical rises in rents, evictions and spiralling rates of homelessness but communities have been organising, fighting back and, whisper it, winning.

Written by: Micha Frazer-Carroll

Inside the wild world of novelty political candidates

From Binface to Buckethead, Elmo to Mr. Fish Finger, Britain has a long history of madly dressed mavericks standing in elections, but who are they, who votes for them and what do they represent? Kyle MacNeill investigates.

Written by: Kyle MacNeill

The activists fighting the mental health crisis

Micha Frazer-Carroll examines the way the mental health crisis has escalated in the last five years and meets those organising to end it.

Written by: Micha Frazer-Carroll

How communities of colour fought back

Micha Frazer-Carroll examines the challenges that the UK’s minoritised communities have faced over the last five years, and reports on the ways that they have come together to organise, support and uplift one another.

Written by: Micha Frazer-Carroll

The everyday voices silenced in our coverage of the Middle East

Until women and young people are heard, we won’t break this cycle of destruction and dehumanisation, argues director Maysoon Pachachi.

Written by: Maysoon Pachachi

Suella Braverman has declared a war on rights that we must win

The Home Secretary's latest attack on the rule of law must be resisted writes lawyer Raj Chada.

Written by: Raj Chada