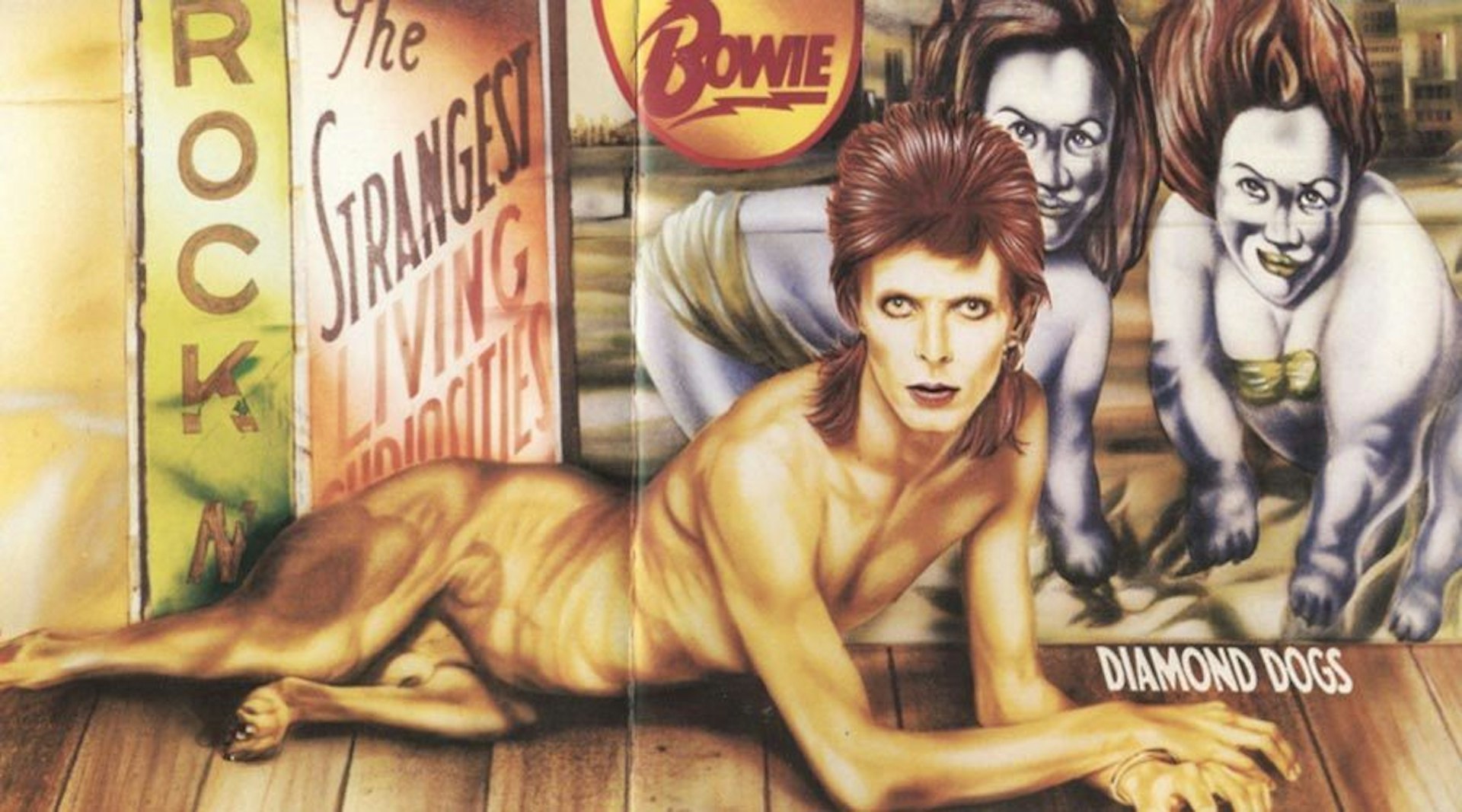

David Bowie’s forgotten art book publishing company

Like most things in Bowie’s career, the art book publishing company he helped start, named 21 Publishing, was way, way over-the-top. From the beginning, there was a serious amount of money and art-world hookups.

The publishing house was started in London in 1998 by David Bowie, West End gallerist Bernard Jacobson, art-patron Sir Timothy Sainsbury and Karen Wright, editor of Modern Painters. At one time, Jacobson was named “possibly the leading art dealer of modern British art”, Sir Timothy Sainsbury is a retired Tory MP and the former chairman of Sainsbury’s supermarkets – basically an aristocrat. Karen Wright was a leading art critic who had worked with Bowie when he was on the editorial board of Modern Painters.

Despite his old-guard partners, Bowie used 21 to publish work that mocked the art-world establishment and made art accessible to the masses. “Everything was either art at an academic level or so dense with art-talk that it excluded 90 percent of the reading market,” Bowie said in a 1998 interview with ARTnews about the kickoff of the new publishing house. “We thought it might be a good thing to go at least halfway to changing that. I say halfway because some of us are maybe more populist than others.”

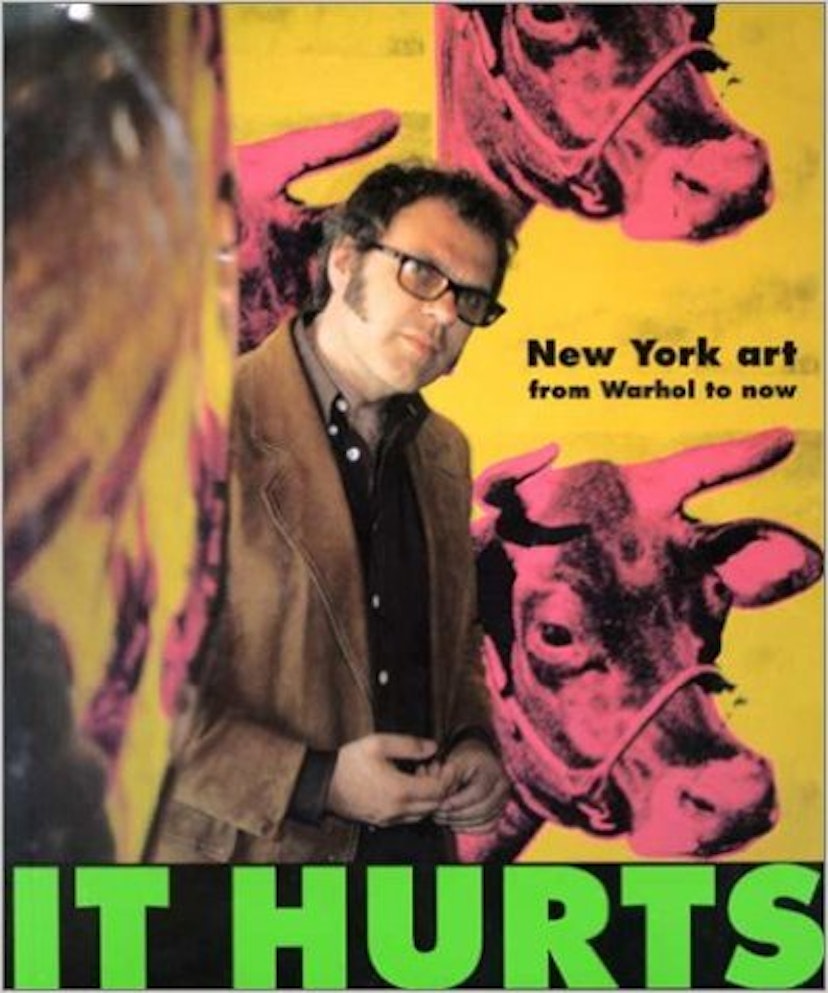

“It Hurts: New York Art from Warhol to Now” by Matthew Collings with photographs by Ian MacMillan

One of 21’s most ridiculous books was solicited by Bowie – fitting for Bowie, the book was the biography of a made-up artist. William Boyd’s Nat Tate: an American Artist 1928-1960 included fake artwork by the esteemed fake artist Nat Tate. The book was meant to get art aficionados worked up over some forgotten artist of the mid-20th century. Bowie wrote a jacket blurb for the book, and organised a release party on April Fool’s Day in Jeff Koon’s New York studio where he read, “Absolutely deadpan, to the assembled New York glitterati.” It’s reported that at the party, white-haired art folk began miraculously ‘remembering’ a retrospective of Nat Tate’s work they had seen some years ago, as if Bowie and Boyd had actually brought the artist to life. It was revealed as a hoax soon afterward.

21 published a hodgepodge of titles. Reporting the World: John Pilger’s Great Eyewitness Photographers was a photo-book that tried to make sense of the role of photojournalism and documentary photography at the dawn of the digital age. “The great documentary form, the still photograph, has become a fashion and fame vehicle, answering to the incessant demands of the market,” John Pilger wrote in the book. “As for people’s true lives, these are deemed unprofitable and therefore of minimal interest.”

“Reporting The World” by John Pilger

Matthew Collings writings had a similar goal of including normal people in art. He had three humorous, down-to-earth books of art history and commentary published by 21. The project was to rid art history of snobbery and pull it down from its ivory tower – giving art what Bowie called, “A confusing, loony relevance.” Collings remembers Bowie telling him that the rock star “didn’t collect any conceptual art, instead if he was interested in something he had his assistants make up a version for him.” Blimey!, Collings’ first book, was published while he was filming a very 90’s documentary on modern art:

Bowie had gone to art-school, but only had his solo first exhibition when he was in his 50s. “If I had some creative obstacle in the music that I was working on, I would often revert to drawing it out or painting it out,” he said in an interview with the New York Times. He had reinvented himself as an art writer when working with Modern Painters, a fairly big art magazine which catered to a wide audience. Moving on to his own indie publishing endeavours, he got more space to take up projects he was passionate about.

“The great freedom within a small indie company like ourselves is that we get the last word on how something is presented and and which books we publish. I would only be a tenacious contributor of ideas at a big house,” he said in 1998. “As long as we break even at year’s end, I think we’ll be happy.” Bowie’s work as an art book publisher is a testament to the constantly changing character of his work and the way he was able to make avant-garde art accessible for normal audiences while challenging the conception of popular music.

Latest on Huck

“I refuse to accept child poverty is a normal part of our society”: Apsana Begum MP on voting to scrap the cap

After seeking to “enhance” the King’s Speech by voting for the scrapping of the controversial two child benefit cap, the MP for Poplar and Limehouse was shocked and heartbroken to lose the Labour whip, she writes.

Written by: Apsana Begum

Is skateboarding really a subculture anymore?

With skate’s inclusion in the Olympics, Kyle Beachy asks what it means for the culture around the sport, and whether it’s possible to institutionalise an artform.

Written by: Kyle Beachy

Autism cannot be cured — stop trying

A questionable study into the ‘reversal’ of autism does nothing but reinforce damaging stereotypes and harm, argues autistic author Jodie Hare.

Written by: Jodie Hare

Bristol Photo Festival returns for second edition

After the success of it’s inaugural run, the festival returns this autumn with exhibitions, education and community programmes exploring a world in constant motion through still image.

Written by: Ben Smoke

Documenting the life of a New York gang leader paralysed by gun violence

New photobook ‘Say Less’ is a complex yet humanising look into a life wrecked by gun violence and organised crime.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The woman who defined 80s Hip Hop photography

A new exhibition brings together Janette Beckman’s visionary and boundary pushing images of an era of cultural change and moral panic.

Written by: Miss Rosen