The photographer documenting the last of the nomadic people

- Text by Josh Jones

- Photography by Cat Vinton

A version of this story appears in Issue 79 of Huck. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Award-winning adventure photographer Cat Vinton started her journey in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Leaving the UK as soon as she graduated from Camberwell College of Arts when she was 21, Cat was desperate to explore the world, so headed for Vietnam to travel the length of the country, backpacking with a friend. She then found a way to cross the border into the lesser-known Laos... “Laos was incredible back in the late 90s – no tourists, just a handful of (mainly) young French people carving out a simple life alongside the beautiful people of this landlocked mountainous country,” she says.

“I ditched my return flight home and stayed for nearly three years.” Those years opened her eyes to a world she didn’t know existed and Cat ended up photographing (on an old Nikon fm2, with b&w film) for Redd Barna (Norwegian Save the Children) and the United Nations.

It’s here that her fascination with Indigenous people living more connected to the natural world began and she’s been working on her People of Borderlands project for over a decade. For Huck she’s given us access to some of the incredible pictures she recently took while documenting Tibetan nomads as they travelled across the Himalayas, oblivious to conventional borders.

Huck: Can you tell us more about the People of Borderlands project? Why did you start it?

Cat: It all started with a curiosity of nomadic people – of another way of knowing the world. From the High Himalayas to the Arctic Circle, the Gobi Desert to the Andaman Sea, I’ve followed a passion, documenting The People of Borderlands – the last of the nomadic people who still roam free, or who once did, across borders – over land and sea, immersed in the natural world. I’ve photographed the Tibetan nomads who are scattered across the Himalayas, among the wild, remote, rugged peaks on all sides of the borders of Tibet (TAR), China, Nepal, India, and Bhutan. Nomads have always moved across land not marked by borders or mapped like the world we know. They have a capacity to orientate themselves in physical space and navigate from place-to-place – wayfinding. Part of this skill involves generating ‘cognitive maps’ in their minds that help them record key landmarks and follow familiar routes. This mental cartography requires not just mapping place but also mapping time. There’s so much conflict globally, around borders, boundaries, and identities – which raises questions around the meaning of freedom and home.

Nomads are envied for their freedom and independence, and hated and feared for these same traits. Across the globe, the loss of land, stolen by imposed borders, has forced apart those who’ve called it home and nurtured it for thousands of years. Aggressive governments are shaping the future of these wild lands, causing the upheaval of human and planetary existence. For thousands of years, the very survival of the nomads has, by definition, depended upon their looking after the land – they live in a harmonious rhythm with the cycles, seasons and patterns of the natural world. Nomadic people have a knowledge, an ancestral wisdom held by their elders. There’s something about how they have always lived in the world which shouts meaningful volumes right now, because we are all struggling with our consumerist, capitalist societies and realising we’ve forgotten the values that really matter. There is an urgent need for new thinking about how we live and what it means to be human. I think many of us, since the pandemic, have been rethinking our own pace of life, our relationship to nature and what we really need to be happy and fulfilled. Nomads are the most resilient people on the planet. Photography is my part in the storytelling of life — with the hope of encouraging people to reconnect to land and community, and to be a part of protecting our natural world and all the ways of life that coexist.

What have you learned from being with the nomads in Tibet?

I’ve learned from the way they live lightly, more freely, in the way they can adapt and be nimble and flexible in their thoughts and actions, and in the balance they have maintained with the natural world – another way of living. About the importance and the purpose of life – a moral and ethical code and about survival and resilience. It’s been incredible to share life alongside the Tibetan nomads – who know how to navigate the highest mountains in the world, who know how to survive in their remote peaks. Who for generations have forged a way of life in rhythm with the seasons, who have a profound respect and intimate connection with the harsh, wild landscape and with the animals and plants of the natural world. Spending time with the Tibetan nomads has taught me that wealth and success are not measured in belongings and status, but in the strength of our human spirit. I have learned to live a more simple, more humble, more connected life and to see the world through a different lens. For the last few years I’ve not called one place home. Instead I’ve roamed, weaving my life and work, more in tune with a wilder spirit and those who still live connected to nature.

This freedom keeps me healthy and strong. I am happiest being outside and on the move.

How did you gain their trust?

My entire project has evolved through empathy and trust – the connections and friendships I make, and whether or not it ‘feels’ right. I have learned to trust my intuition. It has been my guide.

I travel alone. The first thing I do is spend time making a friend with another woman, whom I’m drawn to, who is either nomadic or connected to the nomads, rather than finding a guide or translator. I think as a solo woman I’m not seen as a threat. The nomads accept me, almost protect me, perhaps they see me as vulnerable. For the first few days I don’t touch my camera, I watch how they live, I help, and I smile A LOT. Once I feel I have gained their trust, then I start to use my camera. They intuitively seem to understand my curiosity of their life and begin to share with me their way of life. I have come to learn that if you’re careful with people and you respect them, they offer a part of themselves that they don’t often share.

Although they're borderless, did you see a difference in nomads who were from different areas?

Across the borders of five countries, the nomadic rhythm is in tune with the seasons and their livestock. Their herd of sheep, goats and yak are their lifeline – their welfare is crucial to nomadic existence and survival. The ebb and flow of nuance and gesture, the actual pulse and essence of the invisible forces encountered in the spirit and heart of the Tibetan nomad runs deep. They gift/exchange the khata (a white scarf) a symbol of hope and goodwill. The distinct differences are really only in dress and adornments.

Do they regard themselves as Tibetan or just people of the world? What are they like?

I feel that we all yearn to belong, whether it be to a people or to a place. For the Tibetans they belong as a People. They have a pride in belonging to a land not defined by borders. The Tibetans have maintained a strong sense of identity, an autonomous lifestyle, a culture steeped in tradition with a deep respect for the spirit world. They are beautiful, generous, vibrant, devote Buddhists. Their hearts are open, they are funny, cheeky and curious. They are strong, they are above all, resilient...

Will People of Borderlands ever end?

I still have so many People of Borderlands who I want to spend time with, to learn and share from – the nomadic peoples of the Arctic/ across Africa/Asia and deep into the Amazon... It’s my life project and it keeps growing. As I grow, my work grows.

You might like

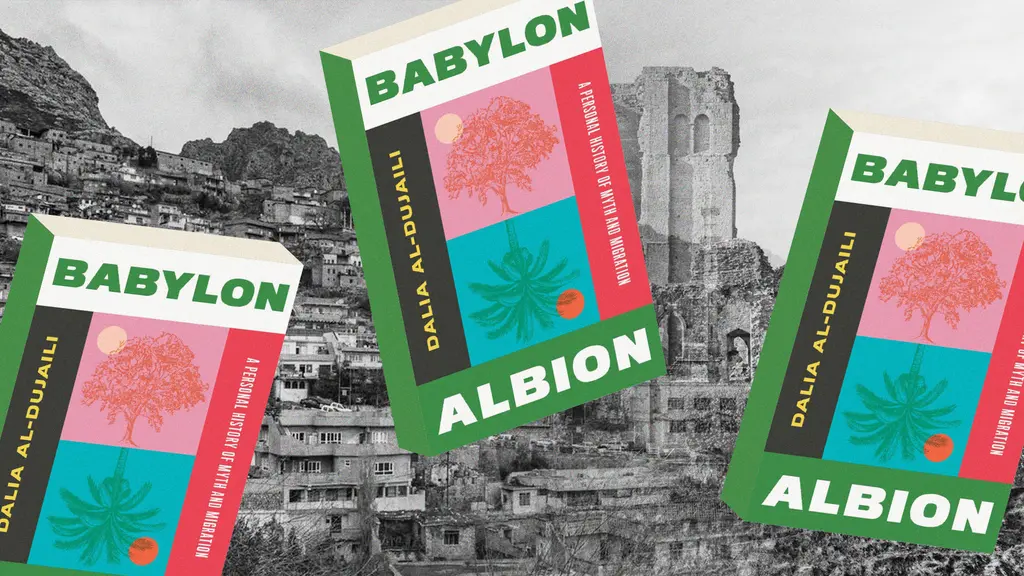

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori