Jason Larkin

- Text by Amrita Riat, Interview by Alex King

- Photography by Jason Larkin

Widowed by the apartheid and the gold rush, Johannesburg is a city shaped by mining. In 2010, photographer Jason Larkin vanished into the South African metropolis to document the impact the old gold reefs have had on the city’s physical and social landscape: barren terra firma, noxious gold dumps, and forlorn inhabitants. Three years on, the British documentarian has emerged with lens intact and a candid photobook, Tales from the City of Gold, which launched at The Photographers’ Gallery on November 7, 2013. Huck caught up with Jason to discuss living in a land of both waste and cultivation.

Could you briefly explain the project, Tales from the City of Gold, in your own words?

It’s basically a project that examines the interaction between Johannesburg and its inhabitants, and the waste product of gold mining.

What made you decide Johannesburg was rich material for your study?

The mine dumps are impossible to ignore, they are just so vast in size. I was fascinated about how they are this direct visual and unavoidable link to the mining past that created Johannesburg, and which ultimately changed South Africa’s trajectory forever.

Mining has greatly affected Johannesburg’s physical and ethnic landscapes. How does the book reveal this?

To make the kind of profits the owners wanted from mining they needed cheap labour, and a lot of it, so the system of apartheid helped the economies of the mining industry as well as many others. The legacy of apartheid is so unavoidable across the country, but in Johannesburg the black and coloured communities are by far the majority who are poor and live in informal camps. Photographing the communities and activities taking place on these abandoned and toxic dumps, I believe highlights this situation.

How did you learn about the history of mining in Johannesburg?

A lot of research from books, talking with and interviewing mining experts and journalists, as well as some dedicated NGOs and environmentalists. Just speaking to people who have lived and known Johannesburg for a long time.

The book says that people barely notice the huge waste dumps, but what effects do they have on people’s lives?

For the communities in the rich northern suburbs, they’ll have little or no impact on day-to-day life. But for the southern suburbs like Soweto; the sand is blown in from these dumps daily during the dry period, is breathed in, gets in food and covers everything, and is sure to have an effect on the communities – one that is little studied. For surrounding parks and wildlife, the water and environment has been badly polluted by acid mine drainage from the mines and mine dumps, it’s a very severe issue that is only getting worse. For the 400,000 who live on them, I’m sure they notice them every day.

The book has a powerful shot of Nicolle praying before he collects water. To what extent are ordinary people aware of the dangers caused by the dumps?

Very little, even in the highly educated northern suburbs. It’s starting to be reported more and more, but with so little attention from the government and with mining companies generally trying to refute smaller studies, there is a vacuum of public understanding. It’s only really NGOs that are building awareness, like FSE who I worked with very closely for access and information.

The industrial process of gold extraction is contrasted with a lone man panning for gold in the book. Are, and were, the benefits of gold evenly distributed?

I think the riches of gold where exclusively distributed through specific white families and European investors. There were obviously a lot of jobs created by it, but the wages for the majority of the workers where so poor, and opportunities to rise within the companies so far and few between. Now, there is in theory a more open and equal opportunity for everyone to get promoted. But the workers at the bottom are still shockingly badly paid, especially considering how hard and dangerous the work is.

There are a number of Fanagalo quotes in the book. Why was it important to include the language in the book?

Fanaglo is a pidgin language that was created by English colonialists in the 19th century. It was adapted early on by mining companies as an easy language for the white mine bosses to learn and use as a command/instruction language. It’s still spoken widely in mines today across South Africa. It’s shocking to know it was ever created, even more shocking to believe that it is still used. To me, it says a lot about the realities in industries like mining across South Africa.

Buy Tales from the City of Gold from The Photographer’s Gallery, or get the special edition at jasonlarkin.co.uk.

For more photo stories, check out Huck 41 – The Documentary Photography Special.

You might like

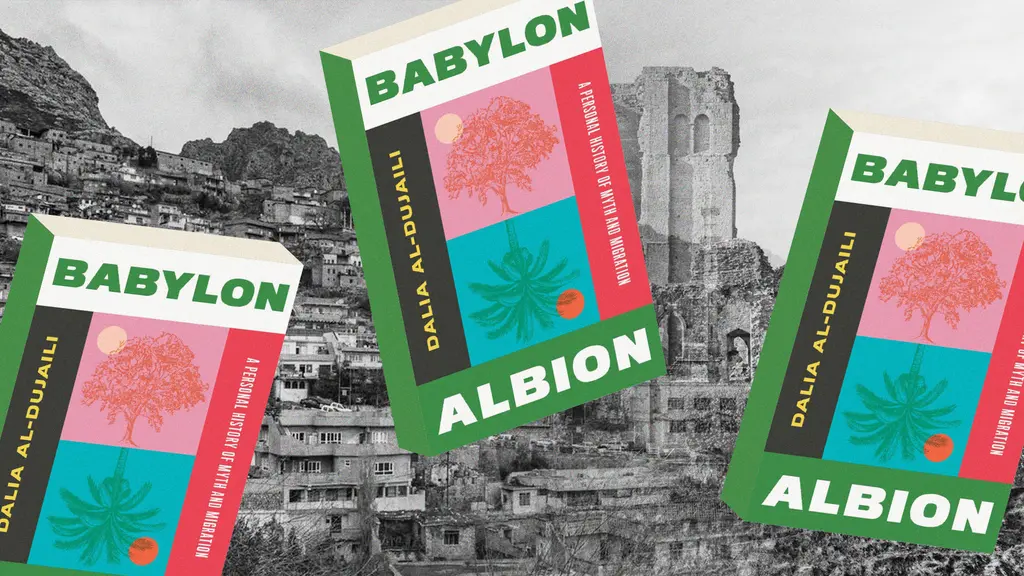

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro