Martha Cooper reflects on a life spent shooting subculture

- Text by Diane Smyth

- Photography by Martha Cooper

Martha Cooper was born in Baltimore, USA, in 1942. She took her first photographs when she was just three years old.

In the 1970s, she became the first woman to secure a staff photographer role at the New York Post. From there, she started a personal project on New York City’s emerging graffiti scene, and, in 1984, published the seminal book Subway Art with Harry Chalfant. It has never been out of print.

In 2015, Cooper’s work was featured in the exhibition Bridges of Graffiti at the Venice Biennale,. Cooper has also published books such as Hip Hop Files (2004), We B* Girlz (2005), Street Play (2006), New York State of Mind (2007), Tag Town (2007), Going Postal (2009) and Tokyo Tattoo 1970 (2012). She was invited to speak on the theme ‘Out There’ at TEDxVienna in 2016.

This autumn, a retrospective of Cooper’s career – curated by Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo founders of BrooklynStreetArt.com – is opening at the Urban Nation Museum for Contemporary Urban Art in Berlin. Titled Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures, it includes unpublished photographs, drawings, journals, and Kodak film wallets, as well as images from her books and her travels around the world, and artworks from her personal collection – such as a pair of paintings by renown graffiti innovator Dondi. As well as that, the exhibition will debut a multi-channel video installation titled The Rushes by Selina Miles, who directed the 2019 documentary Martha: A Picture Story.

Cop drawn from a Mario character from Nintendo’s Donkey Kong video game, Son1 & Rem, Manhattan, NYC, 1983.

What attracted you to, and kept you interested in, photography over all these years?

My uncle and dad owned a camera store. My dad used to take me looking for photos on outings he called “camera runs”. My mom taught high school journalism. So I guess the combination of the two led me to the documentary approach I have today. I’m still out looking. Taking pictures is a way of life.

How did you get interested in photographing graffiti and hip hop culture in New York?

I was a staff photographer for the New York Post and was out on the street with my cameras every day. I began a personal project, documenting kids who were playing creatively among trash in the vast areas of vacant buildings and empty lots on the Lower Eastside near the newspaper’s headquarters.

A boy showed me his notebook with drawings he planned to paint on a wall. I was amazed that he was actually pre-designing graffiti. He offered to introduce me to a graffiti king, Dondi. After meeting Dondi I was hooked. In the process of documenting graffiti I became interested in hip hop as some of the writers were also rappers or breakers. By following graffiti, I stumbled upon hip hop.

Lower East Side, Manhattan, NYC, 1978.

You were a white woman shooting the culture of predominantly much younger black guys in New York. Was that ever an issue, for you or for them?

There have always been white, black and Latino graffiti writers. Being accepted into graffiti culture was and is dependent on skills. Writers’ crews were always interracial. Photography was important because photos were often the only proof of illegal subway pieces. In the 1980s few writers had good cameras so my skills as a photographer were my route to acceptance. Whenever possible, I gave photos to the writers of their pieces.

I was interested that you’ve shot graffiti and hip hop, Japanese tattoos, and kids’ games, and were involved with the City Lore, New York Centre for Urban Folk Culture. Could you say more about your interest in culture and creativity from outside the art establishment?

Before deciding to become a professional photographer, I thought I would like to work in an anthropology museum because I had a longstanding interest in ethnic art. I spent a year at Oxford [UK] at the Pitt Rivers Museum getting a Diploma in Ethnology and then worked on collections at the Peabody Museum at Yale and the Smithsonian.

At Oxford, I learned how important it is to look at art in the context of the cultures that produce it. Graffiti gave me a wonderful opportunity to do that. As an aside, I’m not interested in kids’ games with rules. That’s a different area of study. My interest is in creative play without rules – activities kids invent by themselves when their parents aren’t watching. Graffiti is a good example.

180th Street platform, Bronx, NYC, 1980.

I was interested that you’ve shot both graffiti and murals. What does putting work into the public realm do, compared with putting it into museums, or even into art books?

Public space is open to anyone with the inclination and energy to put their work out there. The gatekeepers are the police rather than gallery owners. Now with the internet, artists can paint a mural and put it online and not have to worry about whether it gets painted over.

In addition, passersby can see, photograph and easily share the work without having to go inside a gallery. Getting your work – including photos – into art books and museums is a much lengthier and more difficult process.

I wondered if you’ve seen changes in the graffiti culture, particularly in the last couple of years. Do you see a renewed interest in politically orientated work post-Black Lives Matter?

Graffiti has gone from being an extreme underground activity of a few to a worldwide movement. There have been many changes in the tools and techniques of writing. Whereas there were only a few colours of spray paint available in the early 1980s, there are now companies producing hundreds of colours and manufacturing specialised spray caps specifically for graffiti.

I have been mostly on lockdown in my apartment for the past five and a half months so I can’t really speak about what’s happening in general. The media has certainly featured a lot of Black Lives Matter murals.

Comfy world view, East Harlem, NYC, 1979.

You’ve been a successful photographer for six decades, which is a feat for anyone – but particularly for a woman in this era. How did you do it?

Determination and persistence. I tried to set attainable goals and then work toward them. I learned to move on from rejections, of which there were many. I pursued my own projects and didn’t wait around for assignments.

What do you see as the photographer’s role? Is it about your vision, or do you have a more journalistic impulse in documenting other peoples’ creativity?

Speaking only about how I see my role, not about photographers in general: I am interested in literal documentation. I try to take pictures where the person or activity can be seen clearly. Although I’m careful about framing and lighting, I don’t look for unusual or dramatic angles.

Even when my photos don’t work aesthetically, I like to think they contain subject matter of interest to future generations. For me, photography is a form of historic preservation.

Skeme, Bronx, NYC, 1982.

Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures is showing at the Urban Nation Museum for Urban Contemporary Art, Berlin from 2 October, 2020 – 1 August, 2021.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

A new book explores Tupac’s revolutionary politics and activism

Words For My Comrades — Penned by Dean Van Nguyen, the cultural history encompasses interviews with those who knew the rapper well, while exploring his parents’ anti-capitalist influence.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Tony Njoku: ‘I wanted to see Black artists living my dream’

What Made Me — In this series, we ask artists and rebels about the forces and experiences that shaped who they are. Today, it’s avant-garde electronic and classical music hybridist Tony Njoku.

Written by: Tony Njoku

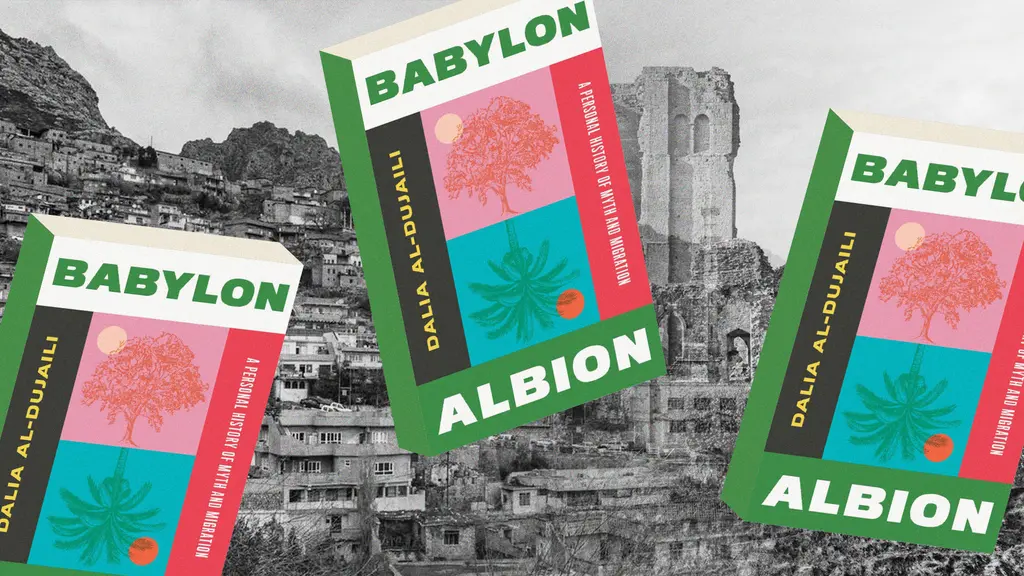

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro