The paranormal drama exploring migration and loss

- Text by Katie Goh

Back in 2008, the French actor Mati Diop embarked on a trip to Senegal, an experience that changed the course of her life and career.

It was there that she met with mutual friends who were about to embark on the dangerous, often deadly, journey across the water to Spain in search of better financial opportunities. The daughter of a Senegalese immigrant, Diop was already concerned with the subject of migration, but it that trip to to his birthplace that made her want to make films about the people who leave their lives behind in the hope of a brighter future.

A year after that trip, Diop released a short film. Titled Atlantiques, it told the real-life story of a young man who made the journey from Senegal to Spain. Now, 10 years on, she’s releasing Atlantics, a feature length film – this time a fictional story about another young man, Souleiman, who makes the same journey across the sea, leaving behind his lover, Ada. While Atlantics is very much grounded in social reality, the film takes an unexpected turn when the ghosts of the departed men return to Dakar and begin to, quite literally, possess the women they left behind.

An intriguing blend of ghost story, romance and political commentary, Atlantics is a breathtakingly confident debut. In May, it saw Diop make history as the first Black female filmmaker to have a film entered into Cannes’ main competition, eventually winning the festival’s second biggest prize. It has also been selected as Senegal’s entry for the Oscars’ best international film category.

To mark the film’s UK release, a busy – and jet-lagged – Diop spoke to us in London about the making of Atlantics, and the migrants, ghosts and waters that haunt it.

Ten years have passed between your short film, Atlantiques and the release of your first feature, Atlantics. What was it about the short that made you want to return to its subject?

The short film was about a young man and his experience of migrating from Dakar to Spain. Migration was, and still is, an important subject to me and I wanted to make a film where the story would be told from the point of view of somebody who experienced it. At that time, their story was being told by the mass media so I wanted [the film] to be from their point of view.

With the short film, while it was an incredible experience making it, I was a bit frustrated that it wasn’t shown to a larger audience. I thought a longer film would be a way of sharing the story [with] more people. I thought for a while about how to portrayal this chapter in Senegal’s history and the wave of migration. With Atlantics, I found I wanted to tell the story from the point of view from the women who were left behind. That was a way of telling the story from my own perspective, because I’m very much connected with the history of migration as the daughter of an immigrant.

Did being an actor yourself help with directing your cast?

Absolutely. The more I direct, the more I realise that acting, writing and directing is one and the same gesture. It’s something that helps my relationship with casting and directing. Acting is very visceral and something I can’t really explain.

I wrote the characters and am able to recognise them in the street so the people I choose need to be very much connected to the social reality of the characters. They have experienced what the characters went through and at the end, they know more than I do about their reality. That’s what really makes us able to collaborate. I have written the characters but they are the characters and we’re able to build the story together.

Of course, being an actor myself, I’m able to understand the place of vulnerability the actors are put in and the trust needed from a director to go beyond your limits and abandon yourself. You need a lot of confidence to do that.

Did you always plan to make Atlantics a ghost story?

Did you always plan to make Atlantics a ghost story?

Yes. I think it came from the person who shared his story with me for the short film. He was told his story of crossing the ocean as an allegorical story and he told me that on the boat, he was there but not really there – dead but not dead.

I’ve spoken to a number of other boys who left Senegal to migrate and when they were talking to me, I felt like they were not really there: they were there in front of me but their spirits were preoccupied with the obsession of being somewhere else. The ocean was this force of attraction and I experienced this kind of ghostliness.

I wanted to have dynamic of death and life in the film. The supernatural element was a way to portray the youth who were living in Senegal and who stayed behind, but who were carrying the weight of the ones who had perished at sea.

The ocean takes on multiple meanings in the film. At first it’s a symbol of hope to Souleiman. But then when he leaves, it becomes something ominous that took him away from Ada.

The ocean is one of the main characters of the film. I wanted to create a very mental relationship with the ocean and to show it as a place of intensity and projection, of obstruction and nightmare, and mostly as something haunted. It’s something that doesn’t give any answers or comfort those left behind. I wanted to use it to confront the mystery of life and death

Migration is a subject that’s been treated in many different ways through media and mostly through the perspective of numbers and statistics – it’s an economic perspective. I think the function of the ocean is to put mystery into life. I don’t think we have all the answers and, for me, Atlantics really started when I had no more words. When I filmed the ocean, I wanted to explore the act of leaving and how you can truly confront the ocean. For me, that’s impossible to rationalise and I have no words for it.

When I put the audience in front of the ocean and that immensity, it’s also putting them in front of mystery. The people who leave take their secrets and the ones that disappear in the ocean will never come back. The water is really the source of the ghostly nature of the film.

The score is integral to creating the mood of the film. How did you work with the composer, Fatima Al Qadiri, to create that?

The score is integral to creating the mood of the film. How did you work with the composer, Fatima Al Qadiri, to create that?

It’s a bit like what I was saying about the actors. The score is not something that’s just added to the film, it’s extremely deep and really essential to the film, especially to what I consider sensitive films. I think the sensitive films that have marked me the most are films where the music and the sound were very specific.

Atlantics has a lot to do with being haunted and Fatima’s music is a spirit itself and something that leaves a very deep mark. Music really starts where the image stops. I think many things can be expressed through dialogue and image but there are some emotions that only music can bring out. I don’t even want to name these emotions because I think they’re so rich and each spectator creates their own emotion depending on what his or her story is. The music is what brings that out.

Atlantics is out now in select UK cinemas and on Netflix from 29 November, 2019.

Follow Katie Goh on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

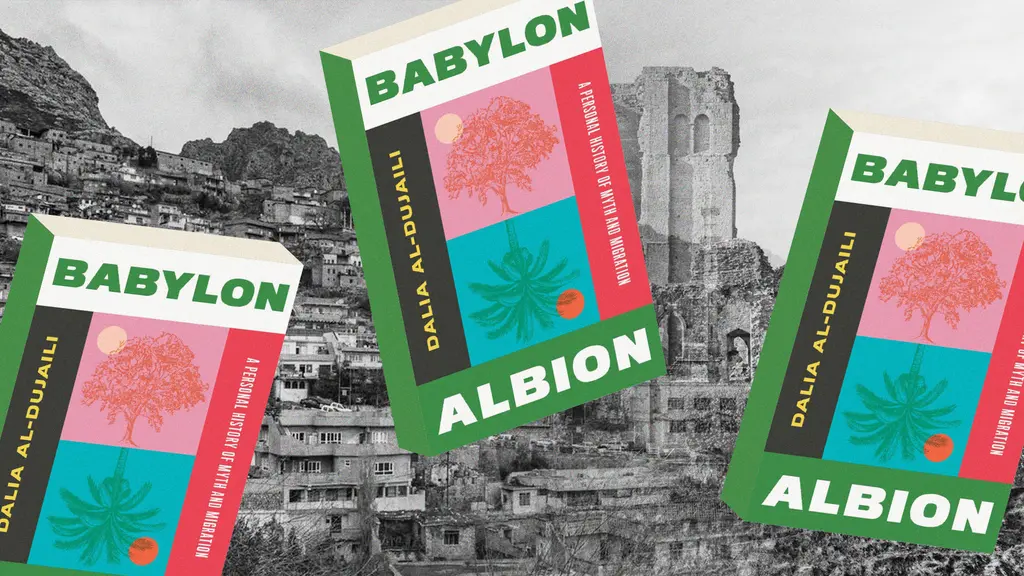

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Remembering Holly Woodlawn, Andy Warhol muse and trans trailblazer

Love You Madly — A new book explores the actress’s rollercoaster life and story, who helped inspire Lou Reed’s ‘Walk on the Wild Side’.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A new documentary spotlights Ecuador’s women surfers fighting climate change

Ceibo — Co-directed by Maddie Meddings and Lucy Small, the film focuses on the work and story of Pacha Light, a wave rider who lived off-grid before reconnecting with her country’s activist heritage.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

In 1971, Pink Narcissus redefined queer eroticism

Camp classic — A new restoration of James Bidgood’s cult film is showing in US theatres this spring. We revisit its boundary pushing aesthetics, as well as its enduring legacy.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The inner-city riding club serving Newcastle’s youth

Stepney Western — Harry Lawson’s new experimental documentary sets up a Western film in the English North East, by focusing on a stables that also functions as a charity for disadvantaged young people.

Written by: Isaac Muk