Unravelling the mystery of America’s missing migrants

- Text by Kathryn Cook-Pellegrin

- Photography by Kathryn Cook-Pellegrin

There is so much human movement in the world right now. Today, we’re seeing the largest numbers of refugees since 1945, and migration is at record highs – but no one can really say how many people go missing on these journeys.

Finding out the fate of missing people is a humanitarian act, and it’s one that deserves greater attention and response around the world. One way to do that is to help tell the stories of those living with that pain.

In our new Missing Migrants project, the International Red Cross has chosen to focus on Honduras and Guatemala because, while there is a global story of migration, these are two countries that are greatly affected by the number of people leaving home. (According to the UN, 500,000 make the journey to Mexico each year – but the numbers of those that don’t make it are still unknown).

We wanted to visit the families of the missing first, to understand what they were going through: what happened to their loved ones, and what mechanisms they are using to search for them. Once there, we shot old photos of the missing family members.

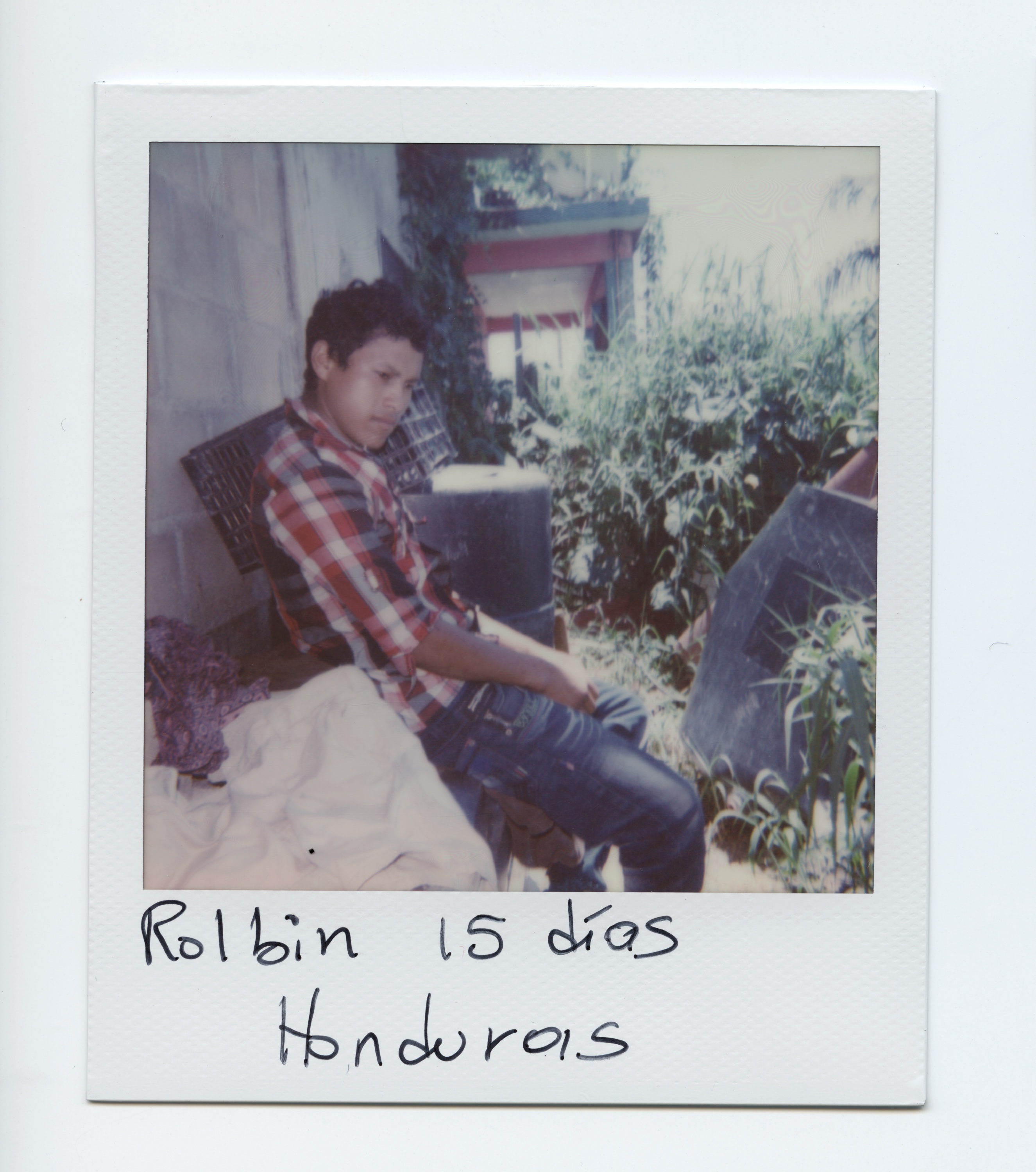

Then, we went to Mexico to follow their route. We met with migrants along different parts of it, heard their stories, and took polaroids of them.

As we went north, the migrant’s stories started to change. They had been through more difficulties by the time they reached Caborca or Altar, in the north. This is why it was important for us to describe how many days they had been on the road. I don’t think many people understand how long it can take, how many things can happen to you, slow you down, or force you to return home. And many do return.

Entering Mexico from the south is an incredibly risky journey. It’s dangerous for the person travelling, but also for the family who is left behind. I gained an extraordinary sense of how vulnerable people are, and at the same time, how tenacious they are to try and make a better life.

It was clear from talking to people that it can vary in how long it takes and the struggles they face. For some, it could be a month, but for others, it could take two or more. I was also really conscious of the women who are especially vulnerable to sexual assault, not to mention families travelling with small children.

For me, these stories are so important because they call attention to an overlooked humanitarian tragedy. When someone goes missing they leave behind families, memories, lives. And that’s true whether it’s in Central America or the Maghreb or the Mediterranean. The places change but the pain that is left behind is the same.

Yonis, on the road for 40 days.

Rolbin, on the road for 15 days.

Rafael, on the road for 29 days.

Maria Delmy, on the road for eight days.

Learn more about the Missing Migrants project on the International Red Cross website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Tender, carefree portraits of young Ukrainians before the war

Diary of a Stolen Youth — On the day that a temporary ceasefire is announced, a new series from photographer Nastya Platinova looks back at Kyiv’s bubbling youth culture before Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion. It presents a visual window for young people into a possible future, as well as the past.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

Analogue Appreciation: 47SOUL

Dualism — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, it’s Palestinian shamstep pioneers 47SOUL.

Written by: 47SOUL

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Amid tensions in Eastern Europe, young Latvians are reviving their country’s folk rhythms

Spaces Between the Beats — The Baltic nation’s ancient melodies have long been a symbol of resistance, but as Russia’s war with Ukraine rages on, new generations of singers and dancers are taking them to the mainstream.

Written by: Jack Styler

Uwade: “I was determined to transcend popular opinion”

What Made Me — In this series, we ask artists and rebels about the about the forces and experiences that shaped who they are. Today, it’s Nigerian-born, South Carolina-raised indie-soul singer Uwade.

Written by: Uwade

Inside the obscured, closeted habitats of Britain’s exotic pets

“I have a few animals...” — For his new series, photographer Jonty Clark went behind closed doors to meet rare animal owners, finding ethical grey areas and close bonds.

Written by: Hannah Bentley