Photos capturing life in the aftermath of the Iraq War

- Text by Isaac Muk

- Photography by Moises Saman / Magnum Photos

In September 2001, a fresh-faced, ambitious Moises Saman was in the infant stages of his photojournalism career. He had recently landed his first full-time role at New York newspaper Newsday, where he spent most of his time capturing the local order of the day in the city – from politics to show business – but had just been assigned to report on one of his first international stories in Palestine. The goal was to make pictures for a piece around the anniversary of the Second Intifada uprising’s beginning. Then, the world turned upside down.

“Of course 9/11 happened and that changed the course of my career,” Saman recalls. “I tend to think as photographers and as journalists we are somewhat a product of our generation and the big events that happen. Obviously, 9/11 was really life changing event for me.”

That Palestine story was dropped and, before he could blink, he was on a flight to Afghanistan as the United States led an invasion vowing to take down Al-Qaeda in its “War on Terror.” But, catching an early glimpse of the ever-shifting goalposts and narratives of the war, Saman quickly found that not all was as it seemed. “Soon we realised that the real target was Iraq all along,” he continues. “So I ended up going to Iraq in 2002 for the first time and staying throughout the war.”

Baghdad, 2008: US Soldiers on patrol along Route Irish, the re-named 7.5 mile stretch from Baghdad’s Green Zone to the airport once dubbed “the world’s most dangerous road.”

A boy hunting in Baghdad during a sandstorm. March, 2003.

In March 2003, from the rooftop of a hotel in Baghdad, Saman was witness to the opening stages of the United States-led coalition’s invasion of Iraq. Documenting the war and its effects on people of both sides of the conflict throughout its duration and during its turbulent aftermath, his work, which has been published in several widely-circulated newspapers, became an important window into the realities of the Iraq War.

In that time Saman come to be regarded one of the world’s leading conflict photojournalists, as well as becoming a member of the renowned Magnum Photos agency in 2014. Now, marking 20 years since the beginning of the invasion, a number of his photographs from his archive are presented in his new monograph Glad Tidings of Benevolence. With devastating photographs depicting burnt out cities, young children with lost limbs, and numerous dead bodies – his pictures show in uncomfortable detail the destruction, horrors, and loss over the past two decades.

Yet it’s also a portrait of the resilience of the population of a country that has been wracked with conflict and war for generations. Unlike many other Western photographers in Iraq, Saman spent relatively little time embedded in the military, instead focusing his attentions towards the civilians of war. “I’m not Iraqi and I wouldn’t pretend to speak for Iraqis,” Saman says. “But even before the American invasion, there were at least two other generations that have been dealing with war – and in any society where there’s war after war, it seeps into the culture and seeps into the day-to-day.

“What I saw were people trying to get ahead with their daily lives,” he continues. One picture he points to depicts a man smartly dressed in smart shoes and a business-ready suit, walking to work as chaos and violence breaks out behind him. “[The picture] really speaks to what it’s like to really live in a war zone, because the clock doesn’t stop. It’s not bombs constantly falling and people hunkering down in their homes. When you’re in a constant state of war, you sort of get on with it.”

Mosul, Salahaddin Province, 2019: A family returning to their destroyed home to salvage their belongings.

Baghdad, 2003: Oil fires set alight over the Tigris River on the even of the invasion to obscure the view of US warplanes flying over Baghdad.

At the heart of the pictures is an exploration of the portrayals of war from afar and its justifications. “I realised some things were off,” Saman says. “I was seeing how different narratives would change over time, and how sometimes we were told official accounts of things that were happening that didn’t really match what we were seeing on the ground.”

From bogus intelligence about weapons of mass destruction to pie in the sky ideas of bringing Western democracy to Iraq, several justifications were broadcast to television screens and printed across newspapers as the war and its atrocities rumbled on.

One notably prescient portrait Saman took in 2008 sees a man pointing an old fashioned hunting rifle at the sky while donning a cowboy-esque hat. His name was Abu Zakaraya – a notorious former Sunni insurgent commander who had flipped to co-operate with American forces, with money exchanging hands in the process. The hat was the first thing that caught Saman’s eye when he came to be interviewed.

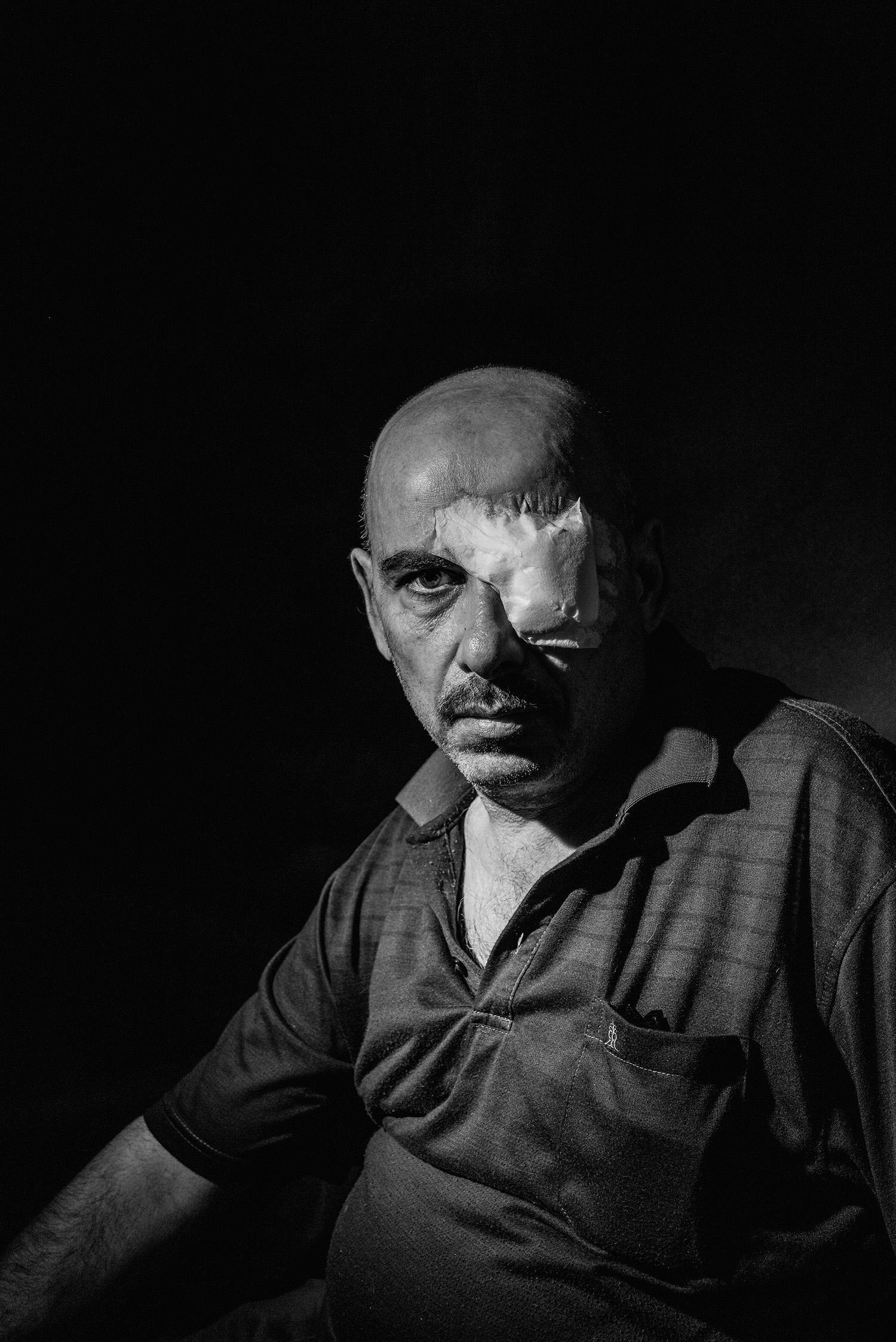

Jordan, 2020: Ahmed, 52, lost an eye during an attack by armed men in Baghdad. Ahmed is a patient at MSF’s Reconstructive Surgery Hospital in Amman.

“When he showed up, he was wearing this quite unusual hat that I remembered seeing somewhere, but couldn’t place,” he says. “Then I realised it was one Saddam Hussein would wear in public. There is a very famous picture where he is wearing this hat and holding this rifle in one arm, shooting the air in a very masculine pose, so I photographed him with the same pose. There’s obviously the parallel with wearing different hats; one day you can wear a bad guy hat and another day you can wear a good guy hat.

“These were obviously people with blood on their hands,” he continues. “They had been dehumanised by the Americans for their horrible violence, but then suddenly the Americans saw a benefit of flipping them. And soon enough they started flipping the narrative and suddenly they were these noble warriors fighting for Iraq.

“Coming face-to-face with [the insurgent leader] and seeing up close the kind of temporality of these narratives – how somebody could be this evil personification and all of a sudden a noble warrior who is aligned with you, was very telling.”

Ramadi, Al Anbar Province, 2016: Survivors of the war living amid the rubble of destroyed buildings.

Baghdad, 2003: A man tries to tame an Arabian horse looted from one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces during the early days of the fall of Baghdad.

As the rhetoric surrounding the conflict twisted and morphed, so did Saman’s attitudes towards his own craft. Glad Tidings of Benevolence is in many ways also a deeply personal journey. He had originally spent much of the early days attempting to uphold one of journalism’s most treasured pillars – of detached objectivity, taught to him by early mentors. But as the war realities of war came up to him and screamed in his face, via a near-death helicopter crash and eight days locked up in the infamous Abu Ghraib prison, he realised it was impossible to separate his own role in the war’s narrative.

“This ideal of being a fly on the wall, this objective observer that can somehow feel a detachment from the scene because you’re looking through a camera – I realised that was all fiction,” he explains. “I realised that the stories that I wanted to be close to were pictures that denounced this human suffering and put a face to Iraqis that were facing the repercussions of bad government, poverty, corruption, and of course violence.

Salahaddin Province, 2010: New and old graves at a cemetery on the outskirts of Samarrah.

“The legacy of this war is still somewhat up in the air, but I bet that if you speak to the families of people that lost loved ones, there’s not much to be contested,” Saman continues. “This was a devastating event for them in particular, because they lost a son, daughter, father, mother – and there’s something unifying about that on both sides.”

Glad Tidings of Benevolence by Moises Saman is published by GOST

Follow Isaac on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro