In Pictures: How Muslim romance novels became a portal to understand women’s lives in Northern Nigeria

- Text by Glenna Gordon

- Photography by Glenna Gordon

I first went to Nigeria in 2012, after many years of working elsewhere in Africa, planning to do a serious project about infrastructure in the continent’s biggest economy and a side project about Nigerian weddings. But, after I crashed my first wedding, my more serious plans fell to the wayside and I realised I could tell the same types of stories about inequality and power through the lens of weddings.

One wedding led to the next, and from the megacity of Lagos in the south I began to wander towards the Muslim north of the country seeking out other nuptials. As I travelled north, I realised I was further and further out of my own element. I wanted to ground myself and centre my perspective by reading more. I asked a friend who knew the area well what I should read. She suggested a book by a female Muslim romance novelist called Sin is a Puppy That Follows You Home.

Subversive romance novels are tied up and packaged at the local market in Kano.

Before I knew anything else, I knew I was all in. That title got to me – I wanted to inhabit that world. My friend explained there was a thriving cottage industry of Littattafan soyayya – love literature written by Muslim women. The books were about love and marriage, sometimes subversive and sometimes submissive, often about the poor girl marrying the rich man, and just as often about fantasies of a better life. One of the first novelists I met was named Rabi Talle. She was young and spunky and, shockingly, unmarried.

Rabi poses for a portrait in front of a photo of friends of hers who were recently married.

Over time, I began to learn more about her own marriage prospects. Up until then, I’d felt so close to her – two spunky unmarried women doing what they do, judgment be damned. But at that moment, I understood how little of her world I would ever penetrate and how little of mine she could even conceptualise.

Guests gist (gossip) at a wedding.

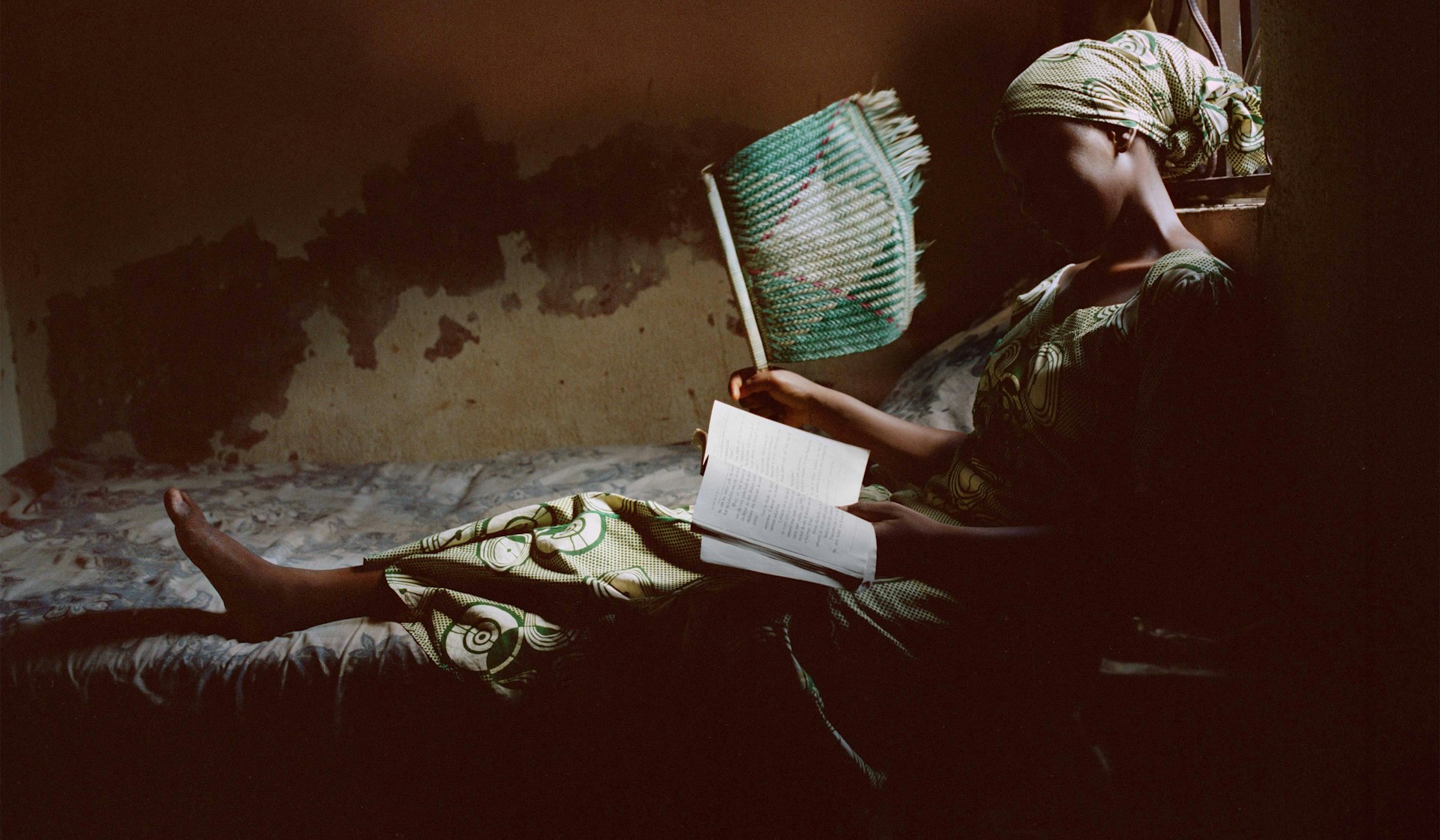

Still, I sat with her for hours, eating fruits so sweet our teeth hurt, going to weddings with her and her sisters packed into the backseat of a car that broke down again and again, photographing her as she wrote in her composition book and went about her daily life.

Ultimately, she lived in a world where she would be someone’s third wife and I live in a world where I make my own choices. I was deeply drawn to the difference between our lives, to understanding what it meant to be a woman in Northern Nigeria, and to what it taught me about being a woman anywhere in this world. I’m writing this from Kano, where Rabi is pregnant and living in a small apartment her husband pays for, separate from his two other co-wives. The first wife has gone to greet Rabi, but she’s never even met his second wife.

Rabi in the courtyard of her office at her day job at the Ministry of Information.

So much has changed in my own life since I first met Rabi. Working in Northern Nigeria has produced some of the most impactful work I’ve done anywhere. When I did stories about the mass abduction of schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram, I won many prizes. Afterwards, at gallery openings in New York and Amsterdam and elsewhere, well-meaning middle-aged women come up to me seeking emotional catharsis: Where are the school girls? What’s happened to them? Are they okay? Have they been raped?

A bride in Kano.

I have no answers for these questions, and no desire to be a spokesperson for these girls or an outlet for someone else’s release.

In fact, these aren’t even the questions I want to ask of this world.

I want to ask questions about what it means to live your life without meeting the expectations of others, what it means to live your life within those expectations.

What if I want to take pictures that don’t confirm what we know about this world but instead overturn our ideas of ourselves and others? Where do we find meaning? Where do we find beauty? Where do we settle in? And when do we seek a way out?

Glenna Gordon’s Diagram of the Heart is published by Red Hook Editions.

This article originally appeared in Huck 52 – The Documentary Photography Special III. Grab a copy in the Huck Shop or subscribe today to make sure you don’t miss another issue.