How the people of Brixton fought to rebuild after the 1981 riots

- Text by Ashley Manning

- Photography by Honey Salvadori

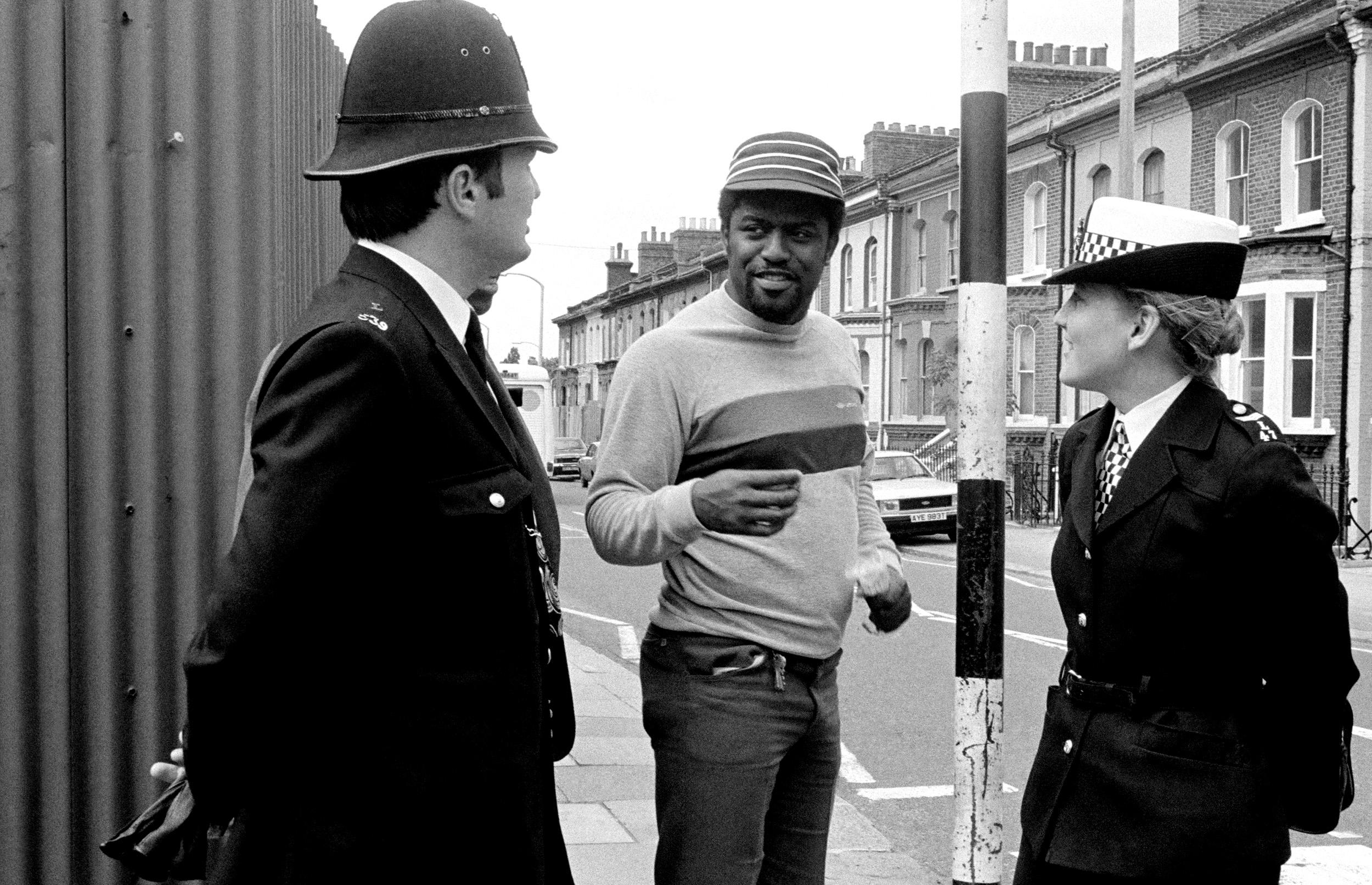

Margaret Thatcher’s reign as British Prime Minister was not kind to Brixton. Unemployment rates had soared, the housing crisis was worsening and much of South London had been left in a state of deprivation and disrepair. Racism towards the area’s large Caribbean community was rife – especially in the police.

In 1981, the people of Brixton took to the streets so their voices could finally be heard. It turned violent – a quiet protest escalated into riots, injuring hundreds and sending a strong message to the rest of the city.

Photographer Honey Salvadori’s Pull it: Pull it, documents not the riots themselves, but how the community came together to rebuild in their aftermath.

The tensions that bubbled in the area were rarely between races; Brixton is famous for its tolerance and the sense of inclusivity towards multicultural residents. Conflicts existed between the dispossessed and those in positions of power.

Squatters inhabited boarded up council houses and a culture of drug use was rife but artists flourished in the cultural melting pot.

Rastafarianism, the prominent youth culture of Brixton in the 80’s, preached freedom and peace, whilst the gay community experienced a new sense of liberation as they became more confident and vocal in their calls for equality.

Brixton was carving a new identity for itself. Salvadori’s book takes a raw, intimate look at the people who were part of one of Brixton’s most transformative decades and helped cement the area’s reputation as a cultural powerhouse.

Why did you choose to document life in Brixton?

When I first moved here in January 1982 it was clear to me that I was living in an area that was on the frontline of social change. It reflected all the effects of Thatcher’s Britain on inner city communities, like mass unemployment and urban decay. Classic subject matter for a documentary photographer.

But Brixton had a special way of dealing with its problems. For some people unemployment and urban decay was an opportunity to create an alternative culture: squatting and radical politics thrived in the streets around the Frontline area.

My book documents this in words and pictures. The pictures are from stories that I worked on during the 80s, from 1983 when I was an absolute beginner. I produced a feature that year for a youth freesheet about Brixton two years after the riots. Then in 1986 another youth magazine asked me to create a photo project about heroin addiction. This was a breakthrough project for me and some of the pictures were widely published. Although the most published pictures were the most gruesome, while the pictures that showed some character and humour were ignored. So I am glad to have had an opportunity to present that photo story in the way that I had originally intended.

In 1987 I worked on a project about Rasta women, which also features in the book, as well as some street pictures that I shot for The Telegraph around the Poll Tax protests in 1991.

The words in Pull It: Pull It are partly from my archive and partly from interviews with people who lived here too and were involved in the squatting subculture and political movements.

I don’t think I ever made a conscious decision to document life in Brixton. It was more a case of life in Brixton reflecting wider issues. In the past couple of years I have started documenting the gentrification in the area. Whilst Brixton has its own particular gentrification issues, I think that once again what is happening here is a symbol of what is happening everywhere.

Complete the sentence: I’m proud to be living in Brixton because…

…it is the most diverse district in the most diverse city in Europe. It also topped the Bremain vote table in the Referendum with 71% voting to stay in the EU… but that’s a different story.

What has most impressed you about the way the people of Brixton rebuilt their community?

Brixton’s community has always been close knit with all the diverse communities getting along with each other, what needed rebuilding was the local economy and the derelict streets. Pull It: Pull It discusses the roots of the urban blight in Brixton in the 1970s and 1980s, and explains why the events of 1981 were a symptom, not a cause, of inner city decay.

What I think is notable, compared to today, was that the Frontline area of Brixton was regenerated in the 1980s in a way that benefitted the existing community and the newcomers (like me). This is a big contrast to what is happening now, with the local council acting in ways that are detrimental to the local people who they are supposed to represent. There are so many campaigns happening here at the moment against decisions made by Lambeth Council: Cressingham Gardens, Network Rail evicting the local traders, Bookish Gyms, and so on…

What do you miss most about the Brixton of yesteryear?

Friday nights at the original Fridge nightclub, which started above a shop on Brixton Road in 1982 before it took over the building near the Town Hall, which is now the Electric.

What has been the biggest loss as Brixton has been gentrified in recent years?

Brixton Splash, which was cancelled this year and replaced by commercial music events in Brockwell Park. That’s a definite sign of the times. I remember the first year of Splash when one of the stages was close to my house. It was sooo loud that the vibrations caused the ceiling in one of my neighbour’s houses to fall down… oops. Sorry,not funny really…

Could you share the most memorable story behind one of your images?

Taking the pictures of the junkie squat was probably the most memorable but for all the wrong reasons. It was a sobering experience watching them take their ritual hit of heroin and cracking jokes about it at the same time. Since when has self harming been funny? But what really sticks in my mind is that the house in Mayall Road that they were squatting is now worth over a £1 million. If only I could remember the number of the house…

Find out more about Honey Salvadori’s Pull it: Pull it.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro