“In a refugee camp along the Thai-Cambodian border, my mother – then seventeen and a survivor of the Killing Fields in Cambodia – had what she believed to be a prophetic dream. In a field, Khmer women, fellow survivors, were frantically clawing with their bare hands into bloodstained dirt searching for an elusive diamond. Without fully understanding what was going on, and to the disbelief of those around her, she serendipitously stumbled upon the diamond wrapped in a blanket of dirt. The following day, she learned that she was pregnant with me. For my mother, in the aftermath of such incredible suffering was this beautiful vision of hope and survival.

My parents were incredibly young at the start of the revolution; they came of age in Khmer Rouge labour camps. They met in the Khao-I-Dhang (K.I.D) refugee camp following the war, where I was born and – at any given time – over 100,000 Cambodian refugees awaited resettlement in the West. In total, nearly 150,000 Cambodians were resettled in America, in communities struggling with pockets of poverty and violence. The refugees were some of the most heavily traumatised and displaced people in modern memory – having survived not only the Killing Fields, but also the arduous trek to sites of refuge, in addition to living and languishing in refugee camps.

We were resettled in Stockton, CA, home to a large Cambodian American community. My parents, having come from an agrarian society and who, because of the war, had no primary education and only a basic grasp of English, were now navigating life in post-industrial America. They quickly assimilated and embraced their new lives in America. English was spoken regularly at home. My father became a devout Christian. Growing up, I had little to no connection to my identity as a Cambodian American. Like most Cambodian American children, and generally children of immigrants, I had no idea what the circumstances were that brought my family to America.

Over three decades have passed since the Killing Fields era, but its shadows can still be felt in the silence between generations of the diaspora and the struggles of the community. Cambodians who lived through the genocide remain silent because they do not know how to speak of what they lived through, and because they literally do not speak the same language as their Cambodian American children. There remains a profound sense of loss and fragmentation when it comes to family and historical narratives. We are disconnected because of intergenerational trauma – elders having survived the Killing Fields, and their American children having survived the inner city.

Like many young Cambodian Americans who grew up in the inner-city, I dropped out of High School. For nearly six years, I worked as a busser at a local buffet. There, I met an elderly couple who convinced me to return to school. After several years of community college, I transferred to Berkeley, which had a small Cambodian Student Association that, for the first time in my life, gave me the means to explore my identity collectively with a group of other young Cambodian Americans. Although I was studying something else at the time, when photography entered my life it was a revelation. Within two years of purchasing my first camera, I had dropped out of graduate school and relocated to New York to learn how to become a photographer.

In the fall of 2010, I set up a makeshift portrait studio in my grandmother’s garage in Stockton, California. There, via the assistance of an uncle, during the portrait session, I spoke to my grandmother about my family’s experience during the Killing Fields for the first time in my life. From that initial conversation, I learned that among the few family possessions saved from before the war was a family portrait that had been buried during the revolution and later retrieved and brought to the U.S. I understood instinctively the significance of that portrait – not as a photograph, but as a tangible connection to the life my family had in Cambodia before the Killing Fields. As my grandmother spoke, I felt a connection to a past that had for so long been withheld from me.

When I first took my grandmother’s portrait, I did not yet know that it was the start of a project that would take me across the country and back, into the homes of Cambodian Americans who would speak of their experiences during the Killing Fields and refugee camps, often for the first time in front of their children. Although I couldn’t imagine it then, the truth is that I became a photographer, in part, in order to tell this story.”

To see more of Pete Pin’s work, head here.

This article originally appeared in Huck 48 – The Origins Issue. Grab a copy in the Huck Shop or subscribe today to make sure you don’t miss another issue.

You might like

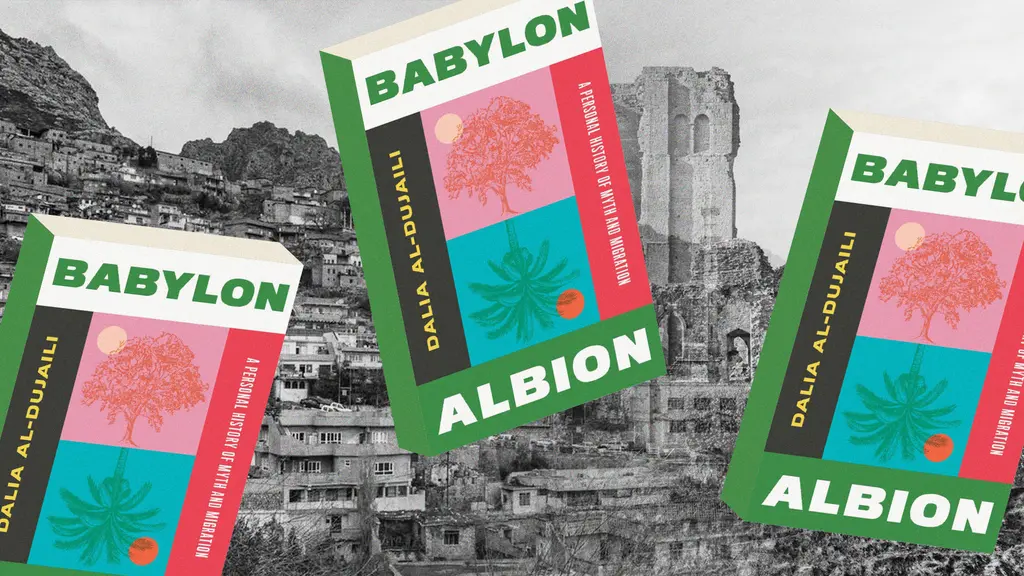

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro