These teenage activists are shaping our future

- Text by Various

- Photography by Corinna Kern (main image)

‘Teen activist.’ What a label. How about, ‘Person who has simply had enough’?

From the school pupils walking out across the US to advocate for gun control and to end horrific massacres, to those fighting homophobia, racism and bigotry in all its forms, we are the ones leading a movement to stamp out poverty, using social media to draw the world’s focus on what has been hidden from view for far too long.

And yes, we’re doing it because we have to, because we’ve been left with no other choice. Ours is a generation that has been truly shafted – by big business and the world’s most powerful elites.

We see the inequality that plagues our communities; we’re in no doubt that a climate change armageddon is inevitable. It’s as if we’re willing to learn the lessons of history and science, while those who’ve reeked havoc – leaving a path of distress and destruction – are somewhat less willing to reflect and change their ways.

But that’s not, by any means, our sole motivation. There’s a deeper driving force – a sense of compassion, respect and determination – that those on the wrong side of history just will not understand. Whereas the language of those who look to ignore us is governed by self-interest, we see the value and potential of humanity in all its forms.

These inspiring activists, and countless others, are laying the foundations for a better world. Maybe you are one of them too. If not, let their stories inspire you to start. There really is no time to waste. Michael Segalov

Photo by Akos Stiller

Karolína Farská – 19, anti-corruption, Slovakia

Last spring, Karolína Farská was getting fed up with Slovakia’s politics. Every time she looked at the news, a corruption scandal seemed to have hit the headlines. “And we’re a really small country,” she says. “I couldn’t see how it was possible for so much corruption to happen here.”

She called a friend to let off steam – moan that no one was doing anything – and he suggested that the pair march through the capital, Bratislava, just to show they, at least, weren’t happy. Before the call had finished, she’d set up a Facebook event. “We thought maybe 20 people would come – our friends, you know – and then we’d go for a beer.” Over 10,000 turned up.

Today, Karolína is one of Europe’s most celebrated activists and one of the few people making the continent’s future look optimistic, persisting even when told to stop. “At first, people thought we were really naïve. They were like, ‘You can’t change anything. Come on, go study.’”

But then she organised a second march, and a third – each one bigger – and the mood in the country changed. “People realised they truly have power,” she says. “It’s not just that they can vote once every four or five years.”

Karolína’s marches were certainly in every Slovak’s mind this February, after an investigative journalist was murdered. He’d uncovered worrying connections between government officials and the mafia. His girlfriend was killed too, shot in the head while on her knees.

“It was like we were standing in front of a question,” Karolína says. “‘Are we going to protect our democracy, our rights, everything we’ve built here? Or are we going to do nothing?’” She co-organised new protests, which this time saw up to 65,000 people march through Bratislava – almost a fifth of its population. Then the prime minister resigned.

Today, she’s got no time to think. There’s meetings to organise (“I’ve one tomorrow, another Sunday,” she says after picking up the phone) and trips abroad to inspire other teens. There’s also dozens of messages to reply to each morning (she ignores the ones demanding to know which foreign power is paying her). A plan to study abroad has been dropped.

Why’s she doing all this when so few people would? “I don’t think I’m unusual,” she says, sounding embarrassed. “I just wanted to show people things aren’t right.” Alex Marshall

Photo by Jason Andrew

Zion Kelly – 17, gun control, Washington DC

Last September – a month before his 17th birthday – Zion Kelly was walking through the park near his home in Washington DC when a strange man asked him for his phone.

Unsettled, Zion bolted and later texted his twin, Zaire, to tell him about the encounter. What Zion couldn’t have known is that the same man – armed with a gun – would kill his brother just two hours later. Eight months on, Zion remembers Zaire as “goofy and always cracking a joke. He was the centre of our friend group.”

A shy kid, Zion often relied on Zaire to make friends for both of them. Growing up in the inner city, gun violence was always in the background. A month before Zaire’s death, the twins attended a vigil for a girl killed close to their house.

“We just accepted it,” says Zion. “Like, we have to be careful. There are guns, but what can we do?”

In February, 17 students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School were killed by a gunman in Parkland, Florida, and 17 others were shot but survived. A few weeks later, a woman named Mary Beth Tinker spoke at Zion’s school about the power of students to change policy.

In 1965, Mary Beth fought her middle school all the way to the US Supreme Court, after she was suspended for wearing an armband to protest the Vietnam War.

Zion felt inspired. He invited Parkland survivors to speak at his school. On 24 March, Zion joined these survivors at March for Our Lives to demand legislative gun control in front of the US Capitol building.

Waiting to speak, Zion trembled. This was Zaire’s thing. His twin had been captain of the track team, a candidate for student council president, the kid who grabbed the mic at a political fair and asked a DC councilman about gentrification.

But when he was introduced, Zion suddenly became confident. “I feel like change can happen, especially with the movement going on,” he says. “I want to step up and honour my brother.”

“Stepping up” means giving up his free time to speak at rallies, at the mayor’s breakfast, in front of congressional representatives and news cameras. It means advocating for a city ordinance, named after his brother, that would expand gun-free zones to create safe passage for students travelling to and from school. It means making sure no one forgets that Zaire was a teenager and a twin, rather than a statistic. Cheree Franco

Photo by Harriet Turney

Legally Black – 17-19, representation, London

“I don’t think a lot of people realised that we’re students,” says Liv Francis-Cornibert. “They were messaging us like, ‘Can we work for you?’ And we were like, ‘We’re literally 18…’”

“I still live with my mum!” quips Shiden Tekle, sat beside her in the gallery space at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton. “I had to turn off my Twitter notifications.”

The two activists, along with friends Bel Matos da Costa and Kofi Asante, make up Legally Black: a London-based campaign group fighting misrepresentation of black people in the media.

The collective formed in September 2017, having met at The Advocacy Academy, a social justice fellowship for young people. But they were thrust into the limelight when their first campaign made headline news in March.

The idea was simple: take iconic film and television posters featuring all-white casts (Titanic, Harry Potter, The Inbetweeners) and replace the characters with black faces – those of friends, family and volunteers. Each poster was accompanied with a simple message: “If you’re surprised, it means you don’t see enough black people in major roles.”

“I guess I’ve always seen negative depictions of black people,” explains Shiden. “Over time, I’ve understood that the media is a really powerful agency in trying to influence and change people and condition them to think a certain thing.”

“We don’t talk about race at all – it’s so structural and ingrained that it’s not overt anymore,” adds Liv. “In order to combat something which is under the surface, you have to look at the institutions where it’s being upheld. For me, the main one that we could go for was media.”

In addition to promoting environments in which black people can articulate their own experiences, the four-piece (all aged between 17 and 19) are determined to highlight issues such as underrepresentation and harmful, inaccurate depictions.

“If there are people in the world, then they should see themselves represented,” says Liv. “Now that we’ve had a taste of that, people aren’t gonna be satisfied with just ending the conversation.” Niall Flynn

Photo by Qusay Noor

Muhammad Najem – 15, citizen reporter, Syria

Fifteen-year-old Syrian Muhammad Najem posted his first Tweet on 7 December, promising to convey all the events being committed by the Assad regime in Eastern Ghouta – a part of Syria which has been under siege since 2013. Muhammad’s motivation was simply to make the world see what was happening to children like him.

The teen has since become one of Syria’s most prominent opposition activist-correspondents, giving a voice to otherwise silenced victims of a war that began in March 2011. “The truth was being concealed by misleading information put out by the Syrian regime,” he says. “I felt compelled to show the world what was really happening.”

Known for videos in which he speaks into the camera like a young war correspondent, Muhammad often interviews other kids about their experiences and asks about their hopes for the future, which typically includes an end to airstrikes and simply “to be allowed to live our lives”.

But Muhammad’s activism has put him in danger. He fears being arrested because “the regime shows no mercy to those who expose it,” adding that the Syrian government has routinely targeted those who condemn its actions, accusing them of generating propaganda. “Bashar Assad’s regime understands the effective role of young people in enacting change in Syria; that’s why he repeatedly imprisons them.”

Muhammad has experienced profound loss for someone so young. His father died when a mosque was destroyed and several of his friends were killed after hostilities escalated in November, wiping out whole neighbourhoods – including his school. “Our lives became primitive. We had our water cut off, our fuel, our electricity.”

In late March, Muhammad left Arbin – the town he’d lived in his whole life – and embarked on a harrowing 30-hour journey to the rebel-held town of Maaret Al-Numan in Idlib, northern Syria. He is now trying to cross the border into Turkey with the aid of a humanitarian organisation.

“I want to be able to lead a normal life and finish my studies,” he says, adding that he hopes to be a journalist one day. “It’s not just me; all the kids here have been deprived of their studies and deprived of their childhood. We want to leave behind the warzone that we’ve been in for seven years.” Lily Fletcher

Photo by Ian Bates

Jamie Margolin, Zero Hour – 16, climate crisis, Seattle

Last year, Jamie Margolin became transfixed by news alerts flashing on her phone: mudslides in Colombia, Hurricane Harvey, Hurricane Maria and, closer to home, “the thick smog that covered Seattle thanks to stronger-than-usual wildfires in Canada.” Instead of simply swiping them away, Jamie decided to do something about it.

“It was already in the back of my mind to start a youth mobilisation movement,” she says. “I was nervous to go there, especially since I’m so young. But last summer I realised I have to take action, even if it’s going to be a lot of action.”

After messaging friends on Instagram – high-schoolers she’d met at a political summer camp at Princeton – Jamie founded Zero Hour, a youth organisation mobilising around the climate crisis.

“We are not a movement that happened overnight,” says Jamie, who connected with adult mentors from the Women’s March as well as young people who protested the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock. “It took hours and hours every day of slow but gradual movement building, and it still does.”

This July, Zero Hour will host a weekend of youth action in Washington DC. The core 25 members – who collaborate online from across the States, and are mostly still at school – will lobby representatives to divest from fossil fuels (“Because how are we going to pass meaningful legislation if our governments are owned by fossil fuel corporations?”) and protest in a march.

The goal is to show how youth are affected by climate change. “It’s not about a sad polar bear on an ice cap. It’s about people’s lives and kids and futures. People say ‘Climate change? We’ll deal with that later.’ But it’s urgent: it’s zero hour.”

Jamie calls climate change the “defining issue of our time,” as it will disproportionately affect young people and people of colour. She has relatives in Colombia, where her mother is from, who live near fracking sites and are worried about the drinking water.

“People are always asking me to plan for my future,” she says. “[But] my generation is inheriting a totally unliveable, uninhabitable planet. Within the next couple of years, we have to turn this around, or else my generation will really suffer.” Rosalie Chan

Photo by Amanda Mustard

Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal – 21, free speech, Thailand

At 14, Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal inadvertently became the face of Thailand’s student activism movement – a daunting role, given the country’s history of draconian lèse-majesté laws, military coups and state violence.

Considered a “disgrace” for his “extreme thinking” by the leader of Thailand’s military junta, the 21-year-old political science student now works with other students at Chulalongkorn University to advocate for educational reform, democracy and free speech.

“We want a free and fair society, to have people be able to speak, to write, to collaborate freely,” says Netiwit, sitting beside a stack of his freshly printed book I Can Love My Country Without Having to be Drafted.

Though Thailand has a long tradition of student activism, past movements – like the 1976 massacre of student protesters by state forces and a royalist mob – are rarely taught in schools.

Their omission from history textbooks, and Netiwit’s own ignorance of them before founding the Thailand Educational Revolution Alliance, is what inspired him and his friends to start a press. They publish their own writings and translate foreign texts, like On Tyranny, so that students can take charge of their own educations.

Netiwit became infamous after questioning Thailand’s mandatory haircut styles for students – first in a school paper and then on national TV. Since then, he’s made international headlines as a conscientious objector, faced sedition charges and been removed from his position in student government.

“If the education here is good, why do teachers have to be afraid of students who raise questions? We are afraid of many things in Thailand: afraid of the military junta and getting in trouble,” he explains, admitting that “it can be very dangerous to live like an activist,” which is why so many of his peers keep a low profile.

He believes that older people are less willing to take risks since it isn’t their own future they’re fighting for. Young activists, meanwhile, push for change because they don’t rely on what hasn’t worked so far.

His greatest hope? “That Thai society will be more open and that more people will challenge the power” of the junta. “We can create that change,” he says with a confident nod. “For our future and for our human dignity, we have to fight.” Micaela Marini

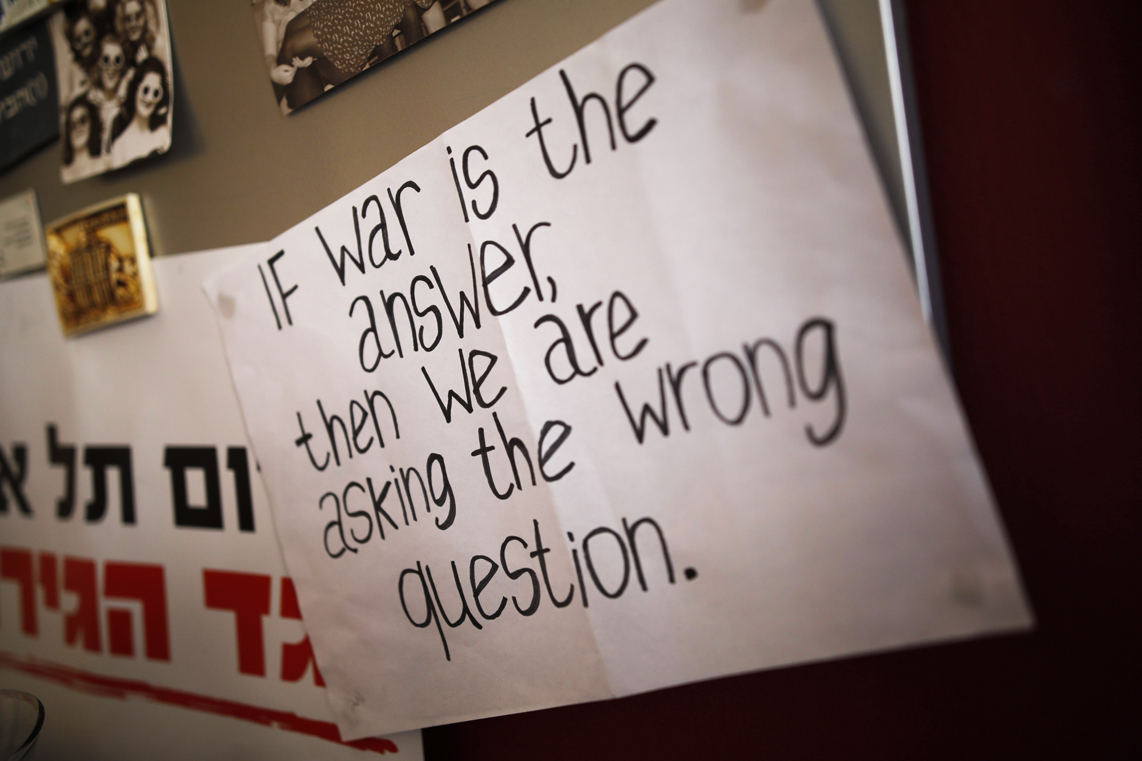

Photo by Corinna Kern

Noa Golan – 19, anti-occupation, Israel

For new recruits, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) is not only an army but a rite of passage: one that smooths your transition into adult society. Choosing not to serve, therefore, marks you out as an other. It can lead to being labelled a threat and even a traitor.

Noa Golan is one of those people, though she never expected to be. Her parents and two older brothers served in the military, so the plan was that she’d follow suit. “My dream was to become a pilot,” says the soft-spoken 19-year-old, sitting in a Tel Aviv cafe. “It went without saying that you joined the army after school.”

But during a scholarship interview for an international high school, a question about Arab refugees from Israel’s 1948 war caught Noa off-guard. “I thought I was very open-minded, very aware,” she says. “But at the age of 16, I had this realisation that I didn’t know much about the conflict’s history. Even though we studied history at school, it was from a very narrow perspective.”

Noa won that scholarship and, for the first time, started getting to know people from countries she considered enemies. Then, with the 2014 Gaza War as a backdrop, Noa’s new peers questioned her about Israel’s actions. That’s when she realised that serving would feel antithetical to her values. “Even for me, it took a long time to accept that I wouldn’t join.”

Photo by Corinna Kern

What followed was a year-long fight for an exemption. As a conscientious objector, Noa had to defend her principles before a committee of seven male officers. When her claims were rejected (twice), she was sent to military prison and appealed for a new hearing. The process put enormous strain on her family, who endured extensive abuse over the controversy.

“Even though my family disagreed with me, they respected me for being loyal to my truth,” says Noa, who absorbed the brunt of the backlash, even in prison. “One girl came up to me and said, ‘We’re not going to talk, we’re going to fight.’ I replied, ‘No, we’re going to be friends.’”

Today, Noa sees her path as one of advocacy. Now a volunteer community manager at a youth centre, she eventually wants to become a marketing strategist for NGOs. Young people, she says, are often afraid to talk about politics, but if individuals like herself continue to take a stand, others will follow. “[Our generation] have to be optimists,” she says. “We don’t have a choice. We’re not allowed to give up.” Rebecca Greig

Michael Segalov is News Editor at Huck and author of Huck’s forthcoming book Resist! How to Be an Activist in the Age of Defiance, published 27 August by Laurence King.

This article appears in Huck 65 – The Coming of Age Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

You might like

Line-up Announced for Palestine Benefit Concert at Wembley Arena

Together for Palestine: Greentea Peng, Jamie xx, Paloma Faith, Damon Albarn and more will join the major Gaza fundraiser at Wembley this September.

Written by: Ella Glossop

As Grindr scams in India rise, its LGBTQ+ community fights back

Red flags — Through mobilising the threat of outing queer folk, scammers are using dating apps to find targets for extortion, violence and blackmail. Mansi Rathee and Amir Bin Rafi spoke to people who have been affected, and reported on the community’s work to support victims and raise awareness.

Written by: Mansi Rathee

Love and rage at the record shattering London Trans+ Pride 2025

Dismantle the cis-tem — With over 100,000 attendees, the Saturday march was the largest trans pride event ever in world history. Cheer Up Luv’s Eliza Hatch captured the action, and recounts its powerful energy.

Written by: Eliza Hatch / @cheerupluv

Euphoric portraits of queer joy and resistance at Trans Pride Brighton

Let us piss — Now over a decade old, the event grew to become Europe’s largest trans pride march. In a year when trans rights have come under the microscope more than ever, we went to this year’s edition, finding grassroots unity and collective rage.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Remembering the radical anti-nuclear Greenham Women’s Peace Camp

Life at the Fence — In the early ’80s, a women’s only camp at an RAF site in Berkshire was formed to protest the threat of nuclear arms. Janine Wiedel’s new photobook revisits its anti-establishment setup and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Led By Donkeys: “It’s weird when right-wing commentators get outraged by left politics at Glastonbury – what did they expect?”

Send them to Mars — With their installation in Block9 launching the billionaire class into space, we caught up with the art and activism crew to chat about the long intersection of music and politics at the festival, how wrong the tech bros are, and more.

Written by: Isaac Muk