The London squatters who resisted evictions in the ‘70s

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by David Hoffman

While living in York in his late teens, British photographer David Hoffman did odd jobs to survive (“some more nefarious than others,” he admits). He began selling pictures to the Yorkshire Evening Post. The paper had no interest in publishing stories on the horrific living conditions of the working class, so Hoffman resolved that this was something he had to pursue for himself.

In the early 1970s, Hoffman arrived in Whitechapel in London’s East End. “It was filthy and felt abandoned,” he remembers. “Much of the housing was semi-derelict and many of the shops were on their last legs. For many it was the place where they ended up when their lives fell apart. It was clearly a dead end.”

Squatters waiting to resist eviction behind the barricaded front door of a squat, Parfett Street, 1973

Many lived in squats to escape homelessness. “Squatting is mostly a communal activity,” Hoffman says. “It brings people together to repair and improve the, mostly broken-down, housing available. The mutual support – and mutual tensions – helped form political understanding and brought us together in activist groups.”

Hoffman found it shameful that the City of London, located just one mile away, offered no support. “While I was powerless to change any of it, I felt that I could and should at least document it,” says Hoffman.

Under the banner of slum clearance and “urban renewal,” the city council decided to tear down the crumbling buildings where squatters lived, with landlords forcing evictions. With the release of Parfett St Evictions 1973 (Café Royal), Hoffman revisits what became the first British protest photography book when it was first published in 1976.

Waiting for the bailiffs before the eviction of squatters, Parfett Street, 1973

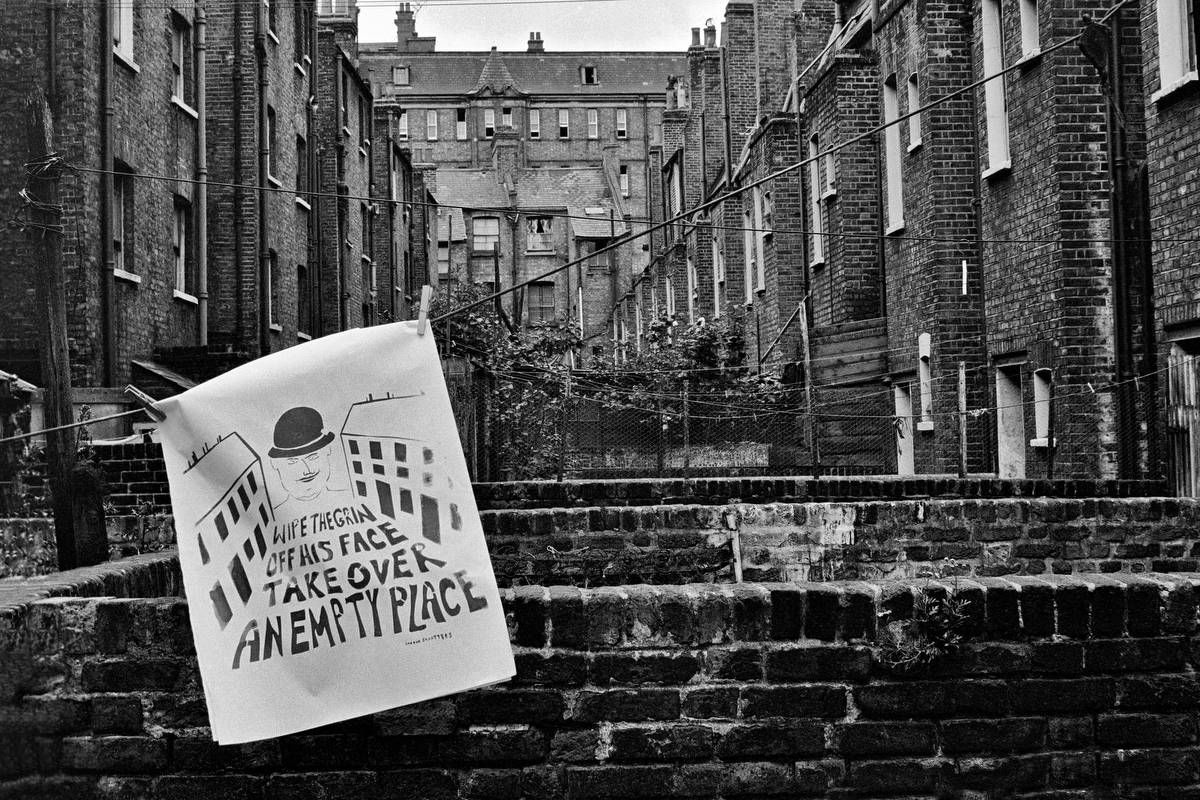

One of many posters around the East End protesting at the eviction of squatters, Parfett Street, 1973

Like many squats the one in Parfett Street housed a wide range of people. “Doris Lerner was the oldest and had been a political activist all her life. Doris would go to auctions of squatted houses and buy them. Being penniless this would delay the sale and extend the life of the squat,” Hoffman says.

“Tony was an early and resolute Gay Rights activist. Duncan was an anarchist and believer in redistribution. Bonkers Piers Corbyn, brother of Jeremy Corbyn would turn up occasionally, try and steal some limelight and then wander off when there was work to be done. We had sex workers, architects, performers, jewellers, musical instrument makers and drug dealers. A healthy mix.”

March on Tower Hamlets Town Hall in Patriot Square protesting against the eviction of squatters, Parfett Street, 1973

Police would regularly harass people around the squats who looked “different,” often stopping and searching them for drugs in the hopes of an easy arrest. “They’d turn up to protect bailiffs in an eviction but they didn’t bother to patrol the area much and generally saw anything to do with us as rubbish work, beneath their dignity,” Hoffman says. “When landlords sent in heavies to make an unlawful eviction, the police were nowhere to be seen.”

Nearly 40 years since these photographs were made, and the lessons they offer are timeless. “We cannot expect the state or those with power to do anything meaningful to alleviate social ills,” Hoffman says. “Banding together is our only route to social justice. If you need a home, take one.”

Police try (and fail) to force a path through squatters and their supporters, Parfett Street, 1973

Fieldgate Mansions, a 19th century tenement block due to be demolished in 1972 but preserved by squatters occupying it

Council official tells squatters who had marched on Tower Hamlets Town Hall that they should go away. Patriot Square, 1973

Fieldgate Mansions, Whitechapel Summer 1985. Scheduled for demolition in 1972 it was squatted by homeless people, artists & Bengali immigrants preventing destruction

Empty house graffitied following the eviction of squatters, Whitechapel, 1973

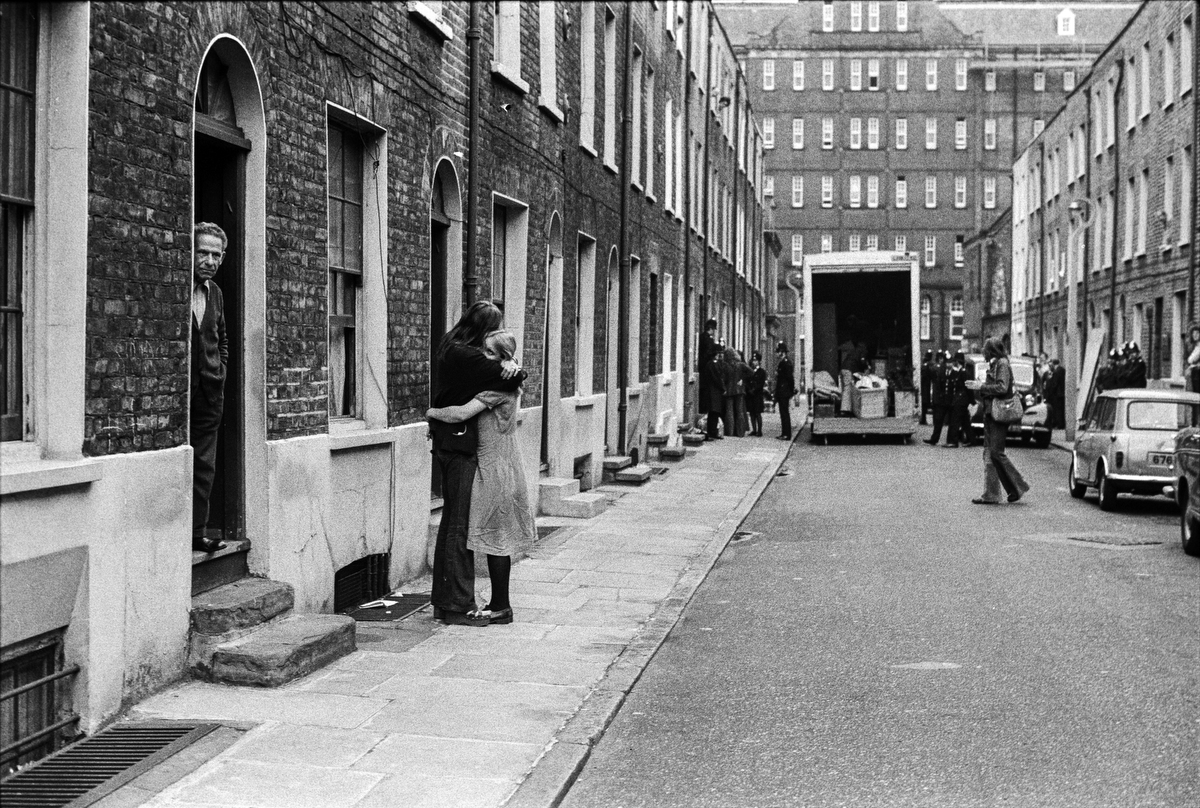

Eviction of squatters from private rented property that was being kept empty in Parfett Street, 1973

Parfett St Evictions 1973 is out now on Café Royal Books.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro