We must change how we think about unemployment

Reports on Covid-19’s impact on unemployment have a tendency to anticipate the end of furlough as a one-off moment that will herald the arrival of an unemployment crisis. This framing overlooks a crucial fact: we are already in one. While the pandemic presents a challenge to measuring the exact scale of the crisis, with various methods such as labour force surveys or the claimant count producing different results, unemployment figures are already staggeringly high.

On January 11, Chancellor Rishi Sunak told Parliament that “over 800,000 people have lost their job since February,” and the Office For National Statistics reported that 2020 saw the biggest increase in the jobless rate in more than a decade, with at least 1.5 million out of work. Anecdotally, over 500 people applied for my part-time, minimum wage retail job in June.

A mass crisis of unemployment is not a temporary blip that will remedy itself with the relaxing of lockdown. As such, any efforts to reimagine the future of work will have to contend with the reality of long-term structural unemployment. Yet, this raises questions: how practically should unemployed people collectively articulate their demands? Who is best placed to represent the self-employed or those who work in retail or hospitality, which have traditionally lower rates of unionisation? In other words, how can unemployed workers organise together in solidarity?

It is in this context that the Unemployed Workers Movement has emerged, supported by think tank Autonomy, whose research focuses on the future of work. Drawing inspiration from the National Unemployed Workers Movement (NUWM), which formed in January 1921 as post-war unemployment reached the one million mark, and at their height commanded around 100,000 members, the new movement launched on January 19, exactly 100 years on.

Jack Kellam, an organiser for Unemployed Workers Movement (UWM), explains that the new movement isn’t hoping to act as “a political party, or a trade union,” but rather as a forum where members will have the ability to decide “what to organise around, and what campaigns people want to support”. Kellam is keen to stress the group is not only open to the unemployed, but also to those on furlough or under employment.

A tradition of participatory democracy was at the heart of a wide variety of tactics taken up by the NUWM in the 20th century, which combined non-violent spectacles, such as the 1938 sit-in at the Ritz, where 100 unemployed men walked into the hotel’s famous Tea Room and asked to be fed, with mass ‘Hunger Marches,’ and a National Legal Department who represented individual unemployed workers. The newly formed UWM takes inspiration from its predecessor’s “sense of moral and political mission,” that “was to give dignity and a sense of political agency to people who find themselves outside of work”.

As capitalism exploits a rise in unemployment as a justification for downward pressure on wages, and reductions in working conditions, there is a potential for hostility and antagonism between those in and out of work. The NUWM were keenly attuned to unemployment’s divisive potential, and were therefore proactive in orchestrating solidarity between employed and unemployed workers, often providing unions with unemployed workers for picket lines, and adopting, “Work or Full Maintenance at Trade Union Rates of Wages” as their official slogan.

National Unemployed Workers Movement https://t.co/WlsqOfqQa2 pic.twitter.com/mJm6bjNiZn

— Paul Veverka (@paulveverka) March 10, 2016

In the present day, feelings of isolation were already a common feature of unemployment. But this has been magnified by the very literal isolation necessitated by the pandemic. “We want to provide that initial space for unemployed people to vent and get things off their chest, to share their experiences, and realise that they’re not alone,” says Kellam. He hopes people can realise there isn’t one response made unemployed. “You’re not unusual for feeling in any one particular way.”

When it comes to having these conversations, statistics can be useful. For instance, a recent report found that the UK’s lowest-paid workers were more than twice as likely to have lost their jobs in the coronavirus pandemic than higher-paid employees. However, this data must be underpinned by the voices of those who’ve lost their jobs. “We don’t want the unemployment crisis to just become about figures, where people’s personal experiences become statistics,” says Kellam. “[This] has been a tendency across the way the pandemic has been dealt with officially.”

The pandemic has provided many with an opportunity to question the centrality of work to their lives, as well as making explicit how we attribute value to it, But unemployed people have not been afforded this period of self-reflection in regards to what they want to ‘do with their lives’. The groundwork was laid in 2014, when David Cameron announced in a speech that “if you’re out of work, you will get unemployment benefit […] but only if you attend interviews and accept the work you’re offered.” This sentiment was made literal in Ian Duncan Smith’s “unashamedly pro-work” welfare reforms, that introduced the sanctioning of claimants from anywhere from three months to three years if they refused to take up a job offer or “community work”.

Underpinning NUWM campaigning in the 20th century was the fight to establish the unemployed as casualties of the capitalist system, both by highlighting that government inaction had deadly consequences – a 1939 demonstration featured a symbolic coffin painted with the words, “He Did Not Get Winter Relief” – but also by organising around the principle that unemployment is an inevitable feature of a capitalist labour market that fails to provide jobs. This sentiment is best expressed by the NUWM oath that begins: “I, a member of the great army of unemployed, being without work and compelled to suffer through no fault of my own.”

I will be teaching an evening online course on "Radical Women 1914-1980" starting on Monday 8th February. This will include looking at to the role of women marchers in the National Unemployed Workers' Movement in the 1930s. More information https://t.co/cWrwmaBDOc pic.twitter.com/uhM1nox5FQ

— Michael Herbert (@MJHerbert) January 11, 2021

Evidently, any solution to unemployment is framed by our ideological construction of unemployed people. The 2010 spectre of welfare dependency reframed unemployment, moving it away from an issue over a lack of jobs following the 2008 financial crisis, and towards a lack of willingness on the part of the unemployed to take up jobs. Mark Fisher expressed how the then-government’s tactic of responsibilisation meant “each individual member of the subordinate class is encouraged into feeling that their poverty, lack of opportunities, or unemployment, is their fault and their fault alone”.

This government’s continued commitment to the myth of voluntary worklessness is evidenced in their proposed solution to the current unemployment crisis: a £238 million Job Entry Targeted Support scheme, a new programme offering “specialist advice on how people can move into growing sectors, as well as CV and interview coaching” combined with the hiring of 13,500 Work Coaches.

But to make real progress, the unemployment crisis must be understood as a structural problem instead of an individual one. Solutions to it should be forced to account for deindustrialisation, the explosion in casualisation and precarious low-paid work, stagnation and a low demand for labour, and in-work poverty. In addition, a structural framing can help “shift the basic goalposts on what we should be demanding for the unemployed,” says Kellam. He wants to move away from “minor improvements” to Universal Credit and towards a totally different way of thinking – such as a Green New Deal, a four-day working week, Universal Basic Income or minimum income guarantee.

It’s not enough to expect increased public sympathy with the unemployed to translate into political action. “We can too easily rely on a sense that short-term changes in opinion will last, or assume that these changes will be readily mobilised in an obviously progressive political direction,” Kellam says. Recently, as respect for key workers was framed by sacrifice and heroism, rather as a question of workers rights, it has been more easily eroded by the public’s general fatigue and frustration. For Kellam, this is why the UWM is vital in this current moment. “We [must] be on the front foot to build solidarity.”

Find out more about the Unemployed Workers Movement on their official website.

Follow Polly Smythe on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Meet the Kumeyaay, the indigenous peoples split by the US-Mexico border wall

A growing divide — In northwestern Mexico and parts of Arizona and California, the communities have faced isolation and economic struggles as physical barriers have risen in their ancestral lands. Now, elders are fighting to preserve their language and culture.

Written by: Alicia Fàbregas

A new book explores Tupac’s revolutionary politics and activism

Words For My Comrades — Penned by Dean Van Nguyen, the cultural history encompasses interviews with those who knew the rapper well, while exploring his parents’ anti-capitalist influence.

Written by: Isaac Muk

A reading of the names of children killed in Gaza lasts over 18 hours

Choose Love — The vigil was held outside of the UK’s Houses of Parliament, with the likes of Steve Coogan, Chris O’Dowd, Nadhia Sawalha and Misan Harriman taking part.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Youth violence’s rise is deeply concerning, but mass hysteria doesn’t help

Safe — On Knife Crime Awareness Week, writer, podcaster and youth worker Ciaran Thapar reflects on the presence of violent content online, growing awareness about the need for action, and the two decades since Saul Dibb’s Bullet Boy.

Written by: Ciaran Thapar

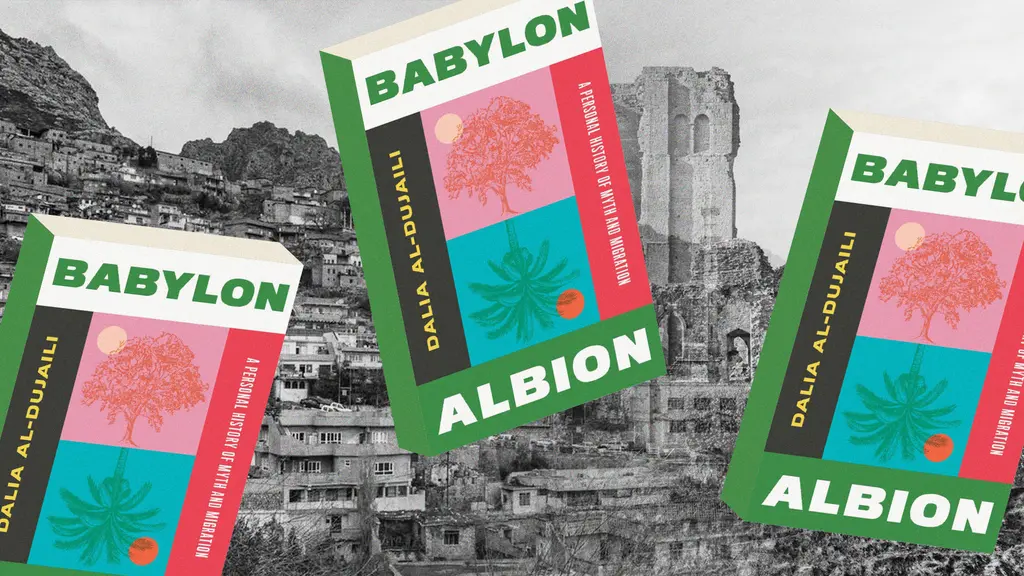

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Jack Johnson

Letting It All Out — Jack Johnson’s latest record, Sleep Through The Static, is more powerful and thought provoking than his entire back catalogue put together. At its core, two themes stand out: war and the environment. HUCK pays a visit to Jack’s solar-powered Casa Verde, in Los Angeles, to speak about his new album, climate change, politics, family and the beauty of doing things your own way.

Written by: Tim Donnelly