Inside the fight to make education radical again

- Text by Emily Reynolds

- Illustrations by Tertia Nash

The year was 1968, and cities across the world were burning. In Paris, people took to the streets, occupying factories and universities: at one point, nearly 22 per cent of the population was on strike. Demonstrations followed in Berlin and Rome, as well as in cities across the US, Pakistan, Mexico and Brazil. Police violence, racism, the rights of women, the Vietnam War, an emerging ecological crisis, state repression, authoritarian governments: dissatisfaction had been bubbling for years in innumerable quarters. The riots and protests were a tangible howl of revolt. This was civil unrest on a global scale.

But in London, amid the occupations and marches that were sweeping the rest of the world, another movement was emerging: a self-organised university, free from the constraints and conservative ideals of those elitist, marketised institutes that dominated higher education. Dubbed the ‘Antiuniversity’, the principles of the project were clear: to really learn – and for everybody to get a fair chance at doing so, regardless of their race, gender or socioeconomic background – universities as they currently existed had to be demolished. Because while university was supposed to be a place of learning, in reality, it was simply a conveyor belt. Students were assessed not by how they had grown, how deeply they had engaged, or by how much their horizons had been broadened, but instead by their eventual value to industry, business or government.

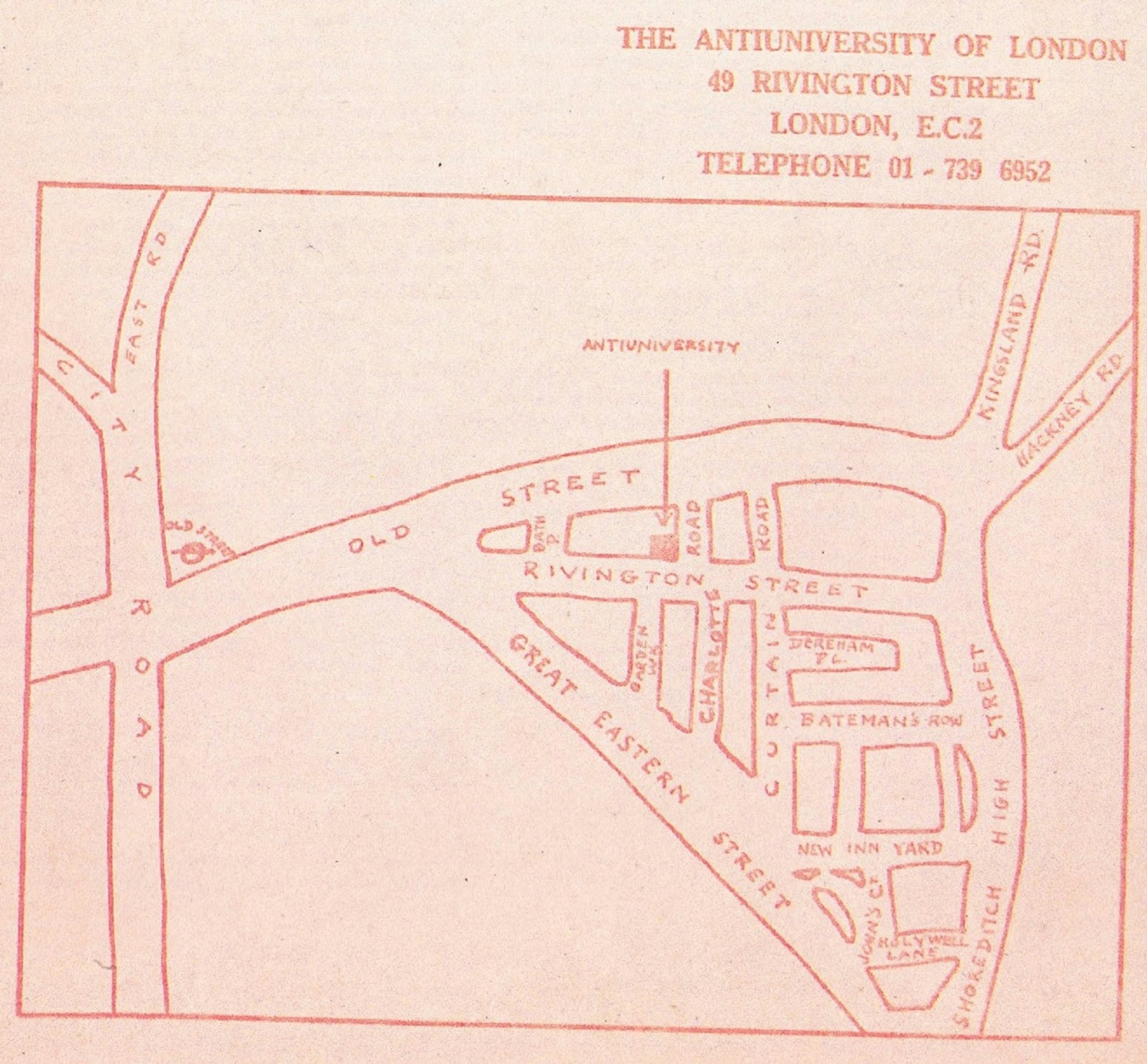

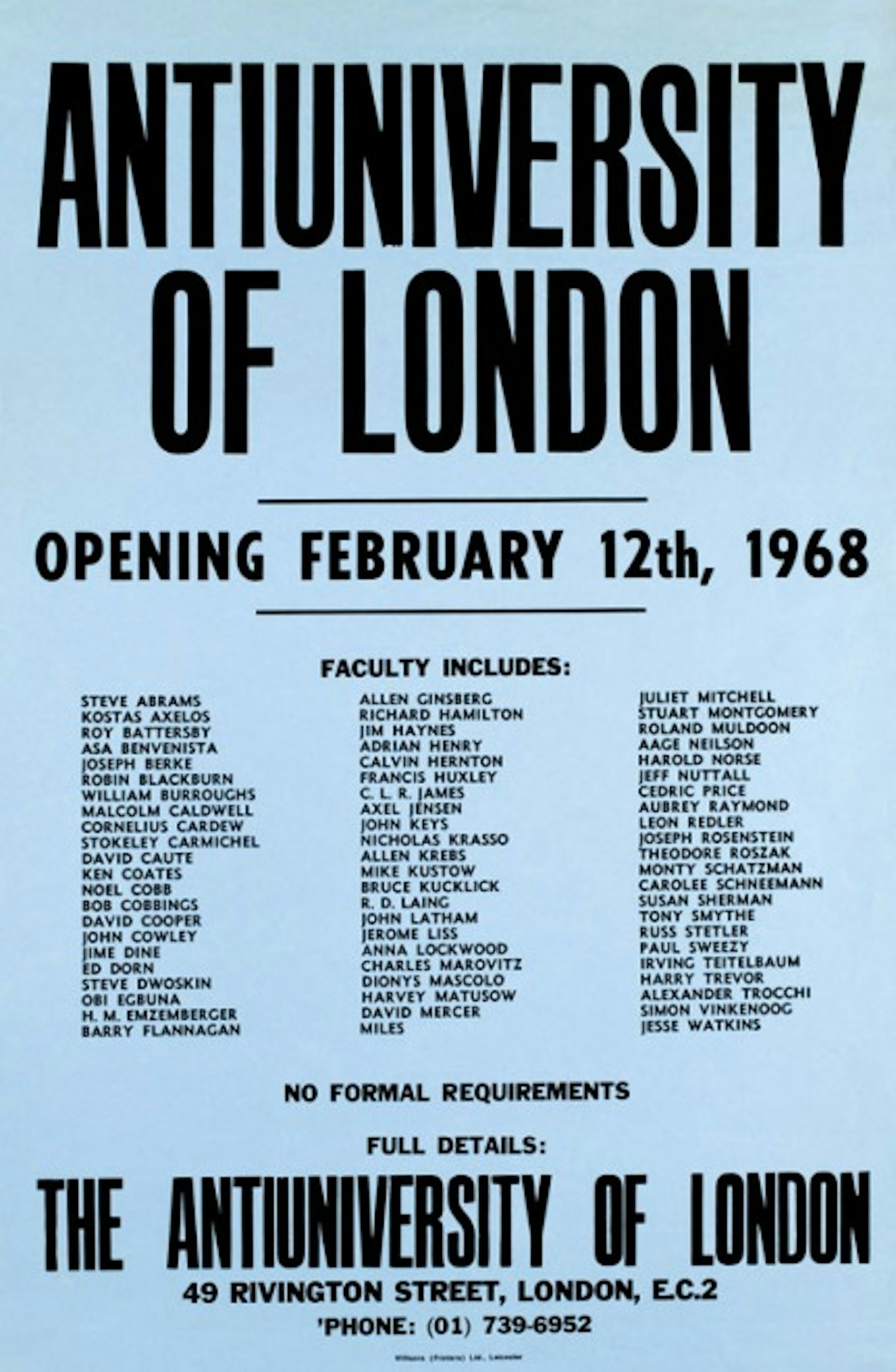

Located on Rivington Street, Shoreditch, the Antiuniversity’s founding committee included Marxist academic Alan Krebs, ‘anti-psychiatrist’ David Cooper, psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell and poet Asa Benveniste. The programme was as you’d expect: courses on black power, the sociology of revolution, psychology and religion, the position of women in society – taught by academics and practitioners such as radical psychiatrist R.D Laing, cultural theorist Stuart Hall and Beat pioneer Allen Ginsberg. No particular educational background was required to enrol, and unlike traditional degrees, you didn’t get a certificate or qualification at the end of it. It was as far away from the traditional experience of ‘going to university’ as you could possibly imagine: an experiment.

At the time, universities and colleges were particularly ripe for revolution. In Paris, philosopher Michel Foucault famously joined the occupation of the Université Sorbonne 8, at one point throwing projectiles with his students at the police outside. Two years later, in 1970, the philosophy department had its accreditation withdrawn altogether after faculty member Judith Miller, daughter of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and a strident Maoist, gave out course credit on a bus, hoping to undermine the university she saw as a capitalist institution.

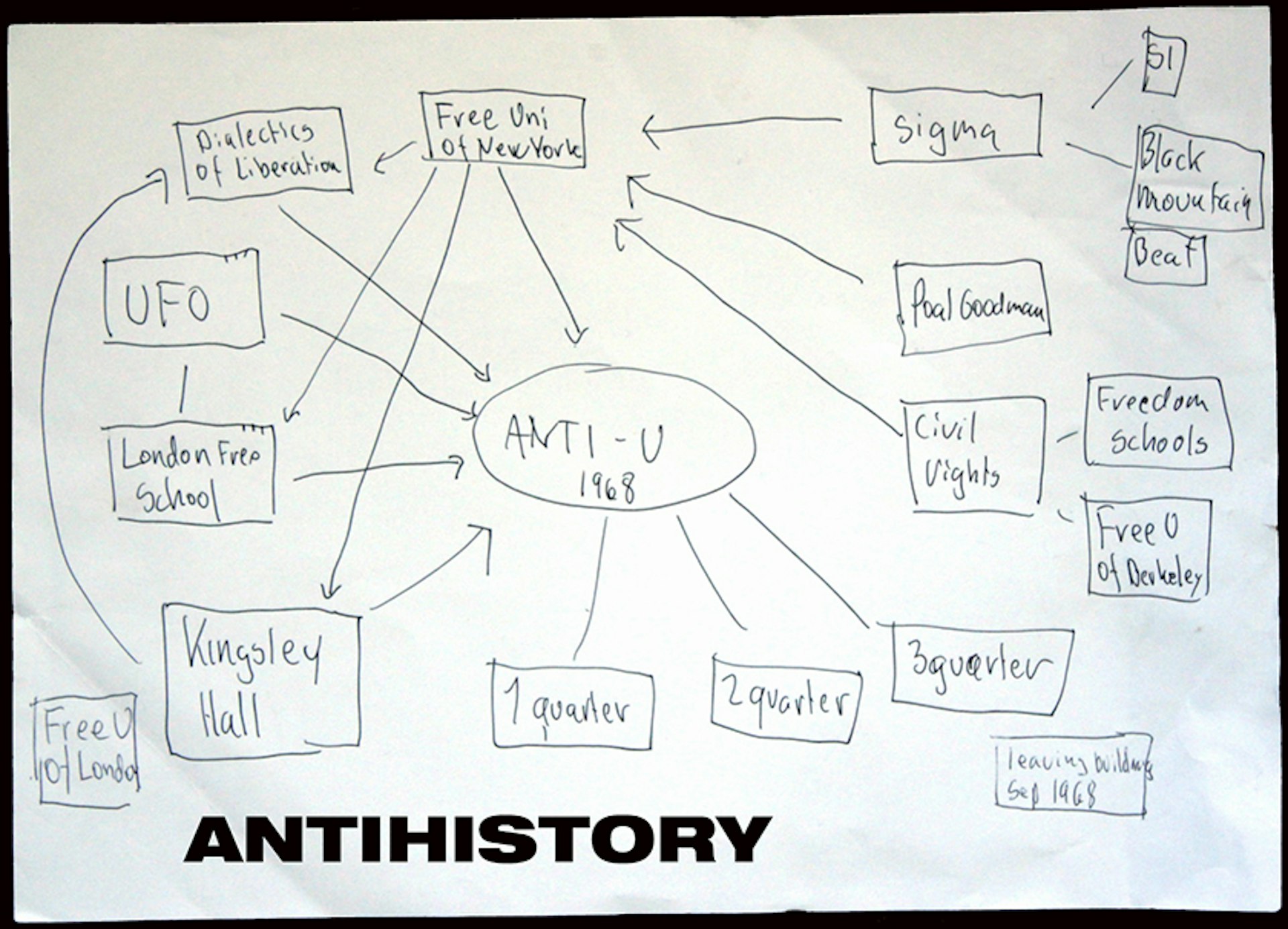

Krebs himself had first-hand experience when it came to rethinking education, having set up the Free University of New York in 1965 with his wife Sharon (who, several years later, stormed the Democratic National Convention naked and carrying a pig’s head in a surreal piece of theatrical activism).

A map of the original site, courtesy of Joseph Berke and PP/JB/IPS, Planned Environment Therapy Trust Archive and Study Centre

In one article on the Free University project in a 1966 issue of LIFE magazine (neatly placed alongside a kitsch advert for Plump ’n Juicy frankfurters), a journalist noted that the session he attended was full not of the “beatniks” he’d expected at all. Rather, he wrote, the room was full to the brim with “real people”. In the article, the organisers described their use of the term ‘antiuniversity’ as a way to reject the “intellectual bankruptcy and spiritual emptiness of the educational establishment” they had been involved with as both students and academics. This phrase would be later borrowed in literature for the Rivington Street experiment.

The dream, unfortunately, didn’t last long. By August, the project was evicted from its Rivington Street headquarters; in suitably chaotic fashion, the organising committee had not paid its bills. For a time, the group continued to hold classes. But the flats and pubs where meetings were held were too disparate, lacked focus; without the energy and stability of the campus, the Antiuniversity floundered and eventually disbanded in 1971.

Fast forward fifty years, and the traditional university is facing the same complaints. If anything, the situation in Britain is even more dire: higher education is as exclusionary as it has ever been, an institutionalised system for upholding both academic and class hierarchy. But the Antiuniversity is back. Reincarnated by a group of activists and cultural workers in London and operating under the name ‘Antiuniversity Now’, it has offered a huge range of free courses every year since 2015 – over 600 panels, walks, talks and workshops have been held in the four years since launch.

Like the 1968 experiment, the programme focuses on radical politics: black liberation, mental health under capitalism, sex work, anarchism. One academic even offers the cultural studies course she teaches at the University of East London in its entirety. Anyone can run an event, and they’re all free: the Antiuniversity not only makes no profit but doesn’t even have a bank account, hoping to remove the transaction from education altogether. The fact that anyone can get involved is also key: it’s decentralised, no one person deciding what is and isn’t worth learning or teaching.

When the founding members first heard about the 1968 Antiuniversity at an event at Hackney Museum in 2015, something clicked for them, co-organiser Shiri Shalmy, 43, says. A speaker was discussing the topic of anti-psychiatry, and mentioned its role in the history of the Antiuniversity. While the reference was only passing – about “two sentences”, Shalmy remembers – the idea sparked something for her and several other attendees of the meeting.

“Myself and [the other organisers] – we didn’t know one another. We just looked at each other and were like, ‘We need to slow this down, we need to see what the Antiuniversity was.’” After initial discussions, the team held an open meeting about the project, expecting 30 people to turn up. In the end, around 200 came to register their interest. In November of that year, they held their first festival: a three-day programme that included events in London, Sheffield, Lincoln and Cornwall. Although the team involved in its running has changed over time, the festival has returned every year.

While the ethos may be the same as the 1968 original, the reincarnation of the project is not – and could not be – an exact replica. “The whole project started from a question,” says Shalmy. “What can the Antiuniversity be like today? But obviously, the more we looked into the Antiuni of ’68, the more we realised that [exactly replicating the model] would be completely nonsense in today’s conditions.”

Shalmy is animated in conversation; she’s quick and sharp when she speaks, deftly darting between different ideas. “It had to start from the institution,” she explains. “It has to start from the fact that education is completely commodified, it’s monetised. It costs nine grand to go to university!”

While the material conditions in which students attend university now are obviously different to those of the 1960s, there are certainly relevant parallels. Where Krebs wrote for Oz magazine in 1968 that the educational system is “the mobility escalator in society”, Shalmy talks of the modern degree as a “ticket to participate” in capitalism. “It has nothing to do with real education, obviously”.

D Hunter, a 39-year-old activist and writer who spoke about his book, Chav Solidarity, as part of the Antiuniversity’s 2019 programme, has similar thoughts on the perceived ‘value’ of the degree. He grew up “well under the poverty line”, and spent his early years in and out of the care system, youth detention and prison. His background made his experience at university alienating: dropping out after a year, he completed his studies with the Open University later on in life.

A map of inspirations and like-minded institutions

Hunter talks slowly, measuring each word carefully, though that’s not to say he lacks passion: his distaste for the elitist institutions of education is barely disguised. Today, he describes the traditional redbrick university as “an unpleasant environment for anyone from my background to be in”.

“The voices of people who are self-taught – whether they’re autodidacts who developed critical reading or literacy skills on their own, or those who have never touched a book ever but have developed their own writing practice – they’re constantly marginalised,” he says. “Their value can’t be quantified in the same way.”

For Hunter, the current state of affairs only serves a particular category of people: those who come from a privileged background. He sees the current system as an overly “bureaucratic” one, where the quantification of people takes precedence. “If you can’t tick certain boxes or prove that what you know is measurable, you’re of no or limited worth.”

“Why would those who have cultural or social power want that to be challenged by those who don’t, who come from economically, racially or otherwise marginalised backgrounds?” he continues. “Of course you want to keep excluding those people, because they have things that can challenge your power.”

It’s this the Antiuniversity exists to challenge; not just the access to knowledge, but the way in which it is shared and distributed. But it is not the only place where radical ideas about educational institutions are brewing. The election of Jo Grady – born in 1984 to a striking miner – to General Secretary for the University and College Union, the largest further and higher education union in the world, is a case in point. She ran on a platform explicit about the problems facing universities today; one that was anti-marketisation and anti-precarious work, and that put solidarity and community at its very heart.

Like Hunter, Shalmy and Krebs before her, Grady notes the ‘exchange value’ of the degree – universities have to demonstrate that education has a measurable outcome, usually via economic contribution. In this sense, universities aren’t providing an education at all – they’re providing a product. “This is essentially what the metrics of marketisation do,” the 35-year-old says. “They have to show they can offer value for money to their ‘customers’, and they need to show the contribution of these subjects, usually to the economy… Health, learning, transformational experiences, relationships between staff and students – it distorts all of that.”

An original flyer, courtesy of Joseph Berke and PP/JB/IPS, Planned Environment Therapy Trust Archive and Study Centre

When it comes to reforming the university as an institution, Grady, like the organisers of Antiuniversity Now, believes changing the funding model is the first step. In her view, the biggest issue with universities is that governance has been left to a group of people who agree with a business model that sees students as a unit from which to extract value. “If you were going to do a scorched earth territory, the governing bodies would have representatives from every demographic,” she says. “You could run a university like a cooperative.”

When asked for his take, Hunter goes even further. “A utopian education would no longer be about turning young people into a worker. It’s about turning them into something else. We decide what that looks like.” If capitalism were to be replaced by an egalitarian society, he says, education would be entirely different: based on “need and desire”, not on value. He also places emphasis on kinship networks: pushing beyond our familial networks to something wider, not just “maintaining and sustaining them, but working on making them deeper and more evolved”.

“And more learning that fits under the academic umbrella of humanities would help – how we learn about our history,” he adds. “The methods that people like Howard Zinn used – basing it not on the history of the winners, but history from the bottom.”

When it comes to Shalmy’s hopes for the future, it’s easy to see why the Antiuniversity looks as it does today. She imagines a world in which “our relationships are not monetised… where the state as it exists has been dismantled, there are no borders, no hierarchies, no flow of commodities”. In that world, she says, education won’t be separate from day-to-day life, nor from the community; it would be collectively organised and relevant to people’s lives – in short, not an activity you do in order to score some points. It would never be for the purpose of making profits, to make an institution richer, or to please a shareholder. “It will be for the joy and self-fulfilment of people and the collective. No one person holds all the knowledge: everyone is a teacher, and everyone is a learner.”

For many of us, ‘education’ – or at the very least ‘university education’ – means elitism, debt, exclusion and stress. We’re certainly not living in the post-capitalist utopia Shalmy, Hunter and Grady have all imagined, while the world that the leaders of the 1968 project hoped to see still feels some way off. But we can see flashes of it in the Antiuniversity. Driven by a desire to create and uphold spaces for real, radical learning – a place where everyone has a stake – they are shaped by whoever takes part. In that sense, it’s an education for everybody.

“This sort of education is not owned by anyone,” Shalmy says. “It’s collectively owned by all of us. Honestly, that is the most compelling part of this story – it belongs to all of us.”

This article appears in Huck: The Utopia Issue. Get a copy in the Huck shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Learn more about Antiuniversity Now on their official website.

Follow Emily Reynolds on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.