Dublin activists are rebelling against slum landlords

- Text by Michael Lanigan

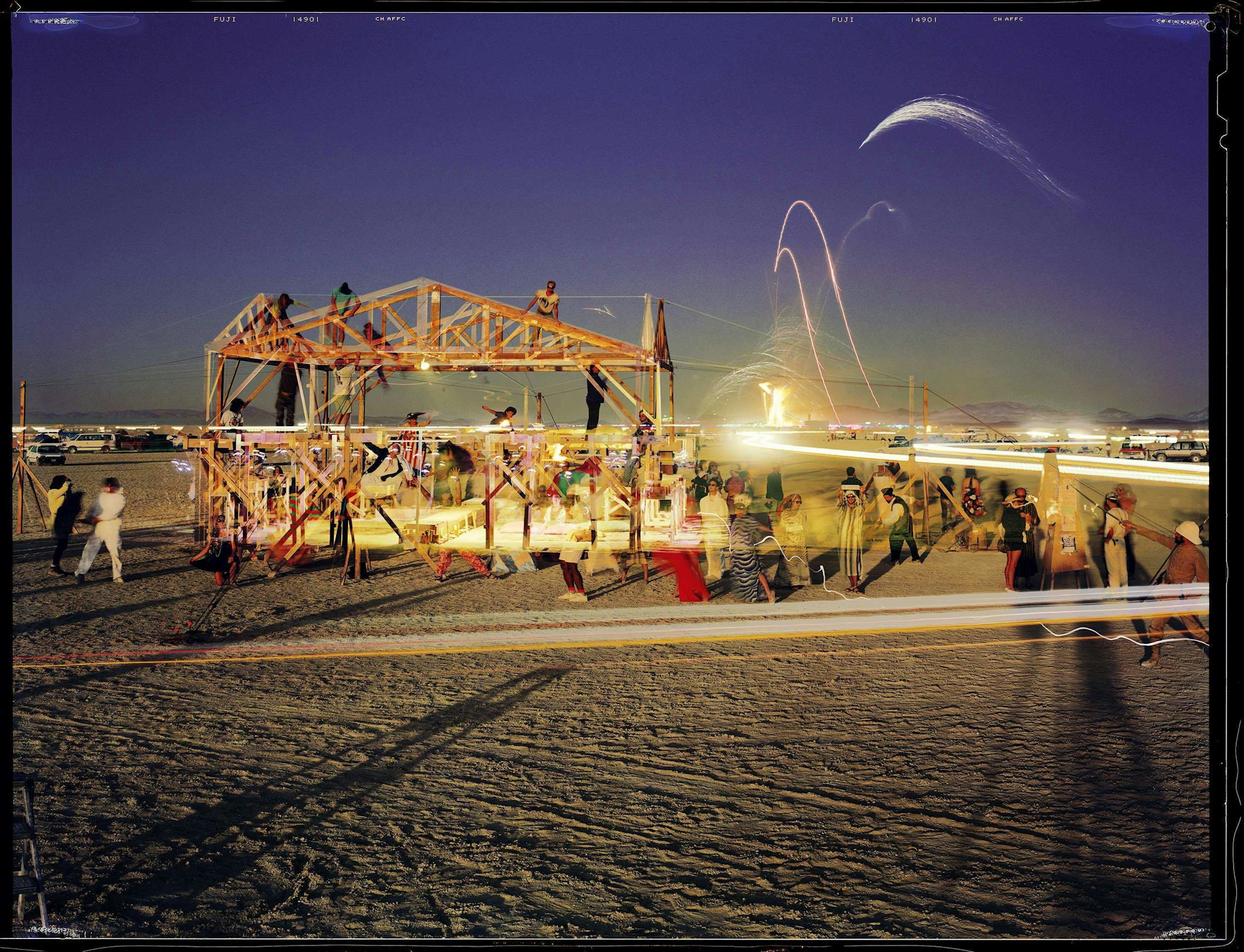

- Photography by Michael Lanigan

“You in the mood for some direct action this evening?”

It’s a few minutes after 7pm on August 7th when these words appear on the Facebook page of Dublin Central Housing Action (DCHA).

Shortly after they’re posted, a crowd of around 100 people begin to gather on Dublin’s O’Connell Street. The group, chanting and brandishing banners, then marches through the north inner city, before reaching a row of old Victorian terrace houses on Summerhill Parade. They stop at number 35.

The house has been vacant for more than three months. On its yellow door, a padlock has been fitted, as have similar ones to other houses on the row. Once the crowd arrives, a “radical element” proceeds to remove the lock on 35, enabling them entry.

By 9pm, three police officers are on the scene. It’s explained to them that this is a civil matter, not a criminal one. So, at least until a court grants the landlord an injunction, their actions will not constitute trespassing.

As DCHA converse with police, they also start sending call-outs on Facebook: they want people to stand outside, live stream the event, and rally behind what is clearly set to be an occupation of the house.

–––––

The purpose of this action was twofold. On a national level, it highlighted the fact that a total of 9,872 people were living in emergency accommodation as of June 2018, marking a 24 per cent increase on 2017. This is then coupled with the rental crisis, which has seen rents rise by an average of 12.4 per cent nationally and 13.4 per cent in Dublin during that same 12 month period.

The second purpose was to call attention to the exploitative practices discovered in neighbourhoods such as Summerhill Parade, which stem from the housing crisis, while feeding into the homeless one.

On May 4th 2018, it came to light that approximately 40 tenants had been living in two houses on the street. Predominantly Brazilian, the majority had moved to Dublin in order to study English. Some had apparently been offered these homes by a company called Golden Rose Accommodation, which targeted foreign students, and which had nobody listed as its director.

A few tenants were lured in under the assumption that they would be sharing these houses with no more than six people. In reality, though, a staggering 120 people were spread out across seven properties on this street, all reportedly owned by the same landlord; one Pat O’Donnell of Pat O’Donnell & Co. Ltd Retirement and Death Benefit Plan.

According to reports, many of the tenants were paying as much as 300 euros per month. That amount afforded them only a bunk bed in a set of hazardous conditions, which – when uncovered during a fire inspection on May 3rd – resulted in a mass case of arguably illegal evictions.

Given two hours to leave their houses on the morning of Thursday May 3rd, in response, several residents brought their cases to the attention of DCHA. The group was able to stall the eviction process momentarily. Unfortunately, in a matter of days, all of the residents were out on the streets.

–––––

“It’s essentially the epitome of the Irish housing crisis,” Oisin Vince Coulter of the student activist group, Take Back Trinity tells Huck on August 8 – the morning after the occupation commenced.

“They were illegal evictions, or at best, semi-legal. You had tenement-like slum conditions in which migrants were being forced to live in properties in a community already ravaged by slum landlords, vulture funds and an overall attitude towards housing that’s disgraceful.”

“Rooms were divided into even smaller rooms,” adds Conor Reddy, also of Take Back Trinity. “There was mould on the walls. The attic was a complete fire trap and there were about four or five living down in the basement.”

“It was a death trap,” says Enda of DCHA. “The landlord would’ve got in trouble if the fire brigade had gone in officially, so he kicked people out. That was the simplest solution.”

“When I moved up here as a student in 2009, I lived in a house like this. We paid 1,200 euros. That’s for four of us in a nicer neighbourhood. Now, these people are paying more for a bunk-bed with 19 others in not as nice a neighbourhood.”

He adds: “The rise in rent and property is going beyond the means of the common people. A lot of the tenants here were barely making enough to get by. One even worked at Google or some tech firm. So, it’s not just the bottom of the social economic strata. Unless you earn way above the average wage in Dublin, you’ll struggle. You’ll end up in bunk beds.”

–––––

Once the initial frenzy of media coverage subsides on the evening of August 8th, plans to ensure that the occupiers maintain a hold on number 35 are already well in motion. Anti-eviction training is provided to as many participants as are willing. Shifts of varying lengths are doled out to avoid creating too much of a pattern when it comes to change-overs and somebody is kept on security at every hour, day and night.

Furthermore, the sheer exposure from online coverage has drummed up more outside support, with almost 200 people subsequently signing up to assist in areas such as postering, door-knocking and presiding over the stall out front. It’s an all-out effort, which manages to get the message out on multiple fronts: Dublin City Council must acquire such properties by way of a Compulsory Purchase Order and convert them into social houses.

“There are up to 10,000 in emergency accommodation, countless sleeping in friends or families houses – the hidden homeless, students travelling miles because they can’t afford to live in these areas,” Peter Dooley of Dublin Renters’ Union explains.

“We have to compulsory purchase them. A roof over your head is a basic human right”, he adds before citing the actions of Louth County Council, which acquired 35 non-derelict vacant homes between 2016 and 2017. “If it’s vacant, a council should have the power to take it back.”

Still, despite this proposal, O’Donnell makes his own intentions clear immediately too. On August 9th, a group of construction workers visit the area to erect steel barricades over the doors of his as-yet unoccupied properties.

Then on August 14th, two men attach a notice to the door of number 35. It reads: “Take notice that all those present on the property are trespassing thereon, are not authorised to be present on the property and are present at their own risk.”

Failure to vacate the building by 11am on the 14th will prompt the owner to bring an application before the High Court that declares the occupiers as trespassers. The notice is signed on the behalf of PJ O’Donnell and Peter McLornan, and while this appears a setback on the surface, in actuality it is a victory for transparency.

Up until the morning of the 14th, O’Donnell was denying all ownership of the houses. Without any other option to protect his own interests, however, he is forced to go public and tie himself to a series of addresses now synonymous with the words “slum” and “tenement”.

“You can actually force their hand until they have no choice but to take responsibility,” Oisin Vince Coulter explains on the morning of the 15th.

“This was never just about the occupation of one building. This is the beginning of a national movement.”

“There’s no intention of leaving. We’ll continue until our plans are met by the council.”

And at 2.30pm on August 15th, this promise is followed up on. A second demonstration is called. Dozens march from Summerhill to the Customs House, which is where the Department of Housing is situated. Only this time, the occupation is of the Department’s lobby.

Loudly declaring their presence via a megaphone, Conor Reddy reads to the crowd a statement: “Dear Minister [for Housing, Eoghan Murphy], a week after the occupation of 35 Summerhill Parade, the groups involved have yet to receive comment from your department on our demands.

“We are taking this opportunity to formally present a list of our demands to you and request a full, written response from your office on their content by tomorrow at noon.”

The demands are that numbers 33 to 39 Summerhill Parade be brought into public ownership by the Compulsory Purchase Order. Further to that, they must be renovated and turned into public housing. All vacant land and property should similarly be taken by the State and local authorities and be used to develop public housing too. Finally, tenant security and fair rents must be ensured, with a total ban on evictions.

It is not long before their message is acknowledged. The sit-in manages to persuade the Department to set up a meeting between representatives of the Summerhill occupation and Minister Murphy.

A movement to reclaim the city is effectively started, meaning that no real blow has been dealt by the time O’Donnell manages to secure a High Court order on the morning of Friday, August 17th.

35 Summerhill Parade is confirmed as having been vacated by 9am on that same day. At 1.30pm however, a ‘Homes for All’ banner is up again. Only this time, it’s on the other side of the north inner city with Dublin Central Housing Action sharing a fresh shot of a new building.

“Introducing 34 North Frederick Street,” the message reads. “The struggle continues here.”

Follow Michael Lanigan on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.