The ex-police officers fighting to end the war on drugs

- Text by Rebecca Tidy

- Illustrations by Simon Hayes

It takes a lot of effort – and manpower – to wage a war on drugs. The Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) – which was introduced 50 years ago this week – has filled prisons and destroyed lives without reducing the availability of illicit drugs or the power of criminal organisations. On top of this is the staggering £535 million that drug arrests cost annually in England and Wales alone. Clearly, the MDA has been a disastrous failure and reform is needed urgently to resolve this ongoing public health crisis.

With this in mind, it’s perhaps unsurprising that it’s not just prominent figures on the Left advocating for decriminalisation – in fact, there’s growing support among serving and former police officers, too. Just last year, the West Midlands became the latest police force – alongside Thames Valley, Avon and Somerset, Durham and North Wales – to offer help rather than a criminal record to people caught with drugs.

This gradual change in attitudes has led to the establishment of Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP): an organisation for police officers, undercover operatives and intelligence workers hoping to change the global narrative around drug use and supply. LEAP UK has hundreds of members across the country, all of whom challenge the stereotypical law enforcement narrative around controlled substances. They claim that while big drug seizures might look good in the press, they’re an illusion of success that simply deceives the public, as police action never reduces the size of the market – it only reshapes it. And this changing shape has led to the growth and corrupting power of international organised crime.

Members seek to educate the public, media and policy-makers about “the failed, dangerous and expensive pursuit of a punitive drug policy”. They often run workshops about the impact of the MDA on police and community relations, and societal health and wellbeing, among other topical issues. Collectively, they hope this will restore the public’s respect for law enforcement, which they feel has been greatly diminished by its involvement in imposing drug prohibition.

There’s no societal benefit to huge drug investigations or hefty punishments, even for big-time crack and heroin dealers, LEAP argues. Instead, the organisation’s members note that Heroin Assisted Treatment in Europe and safe supply in Canada has reduced criminal heroin markets in a way that policing cannot.

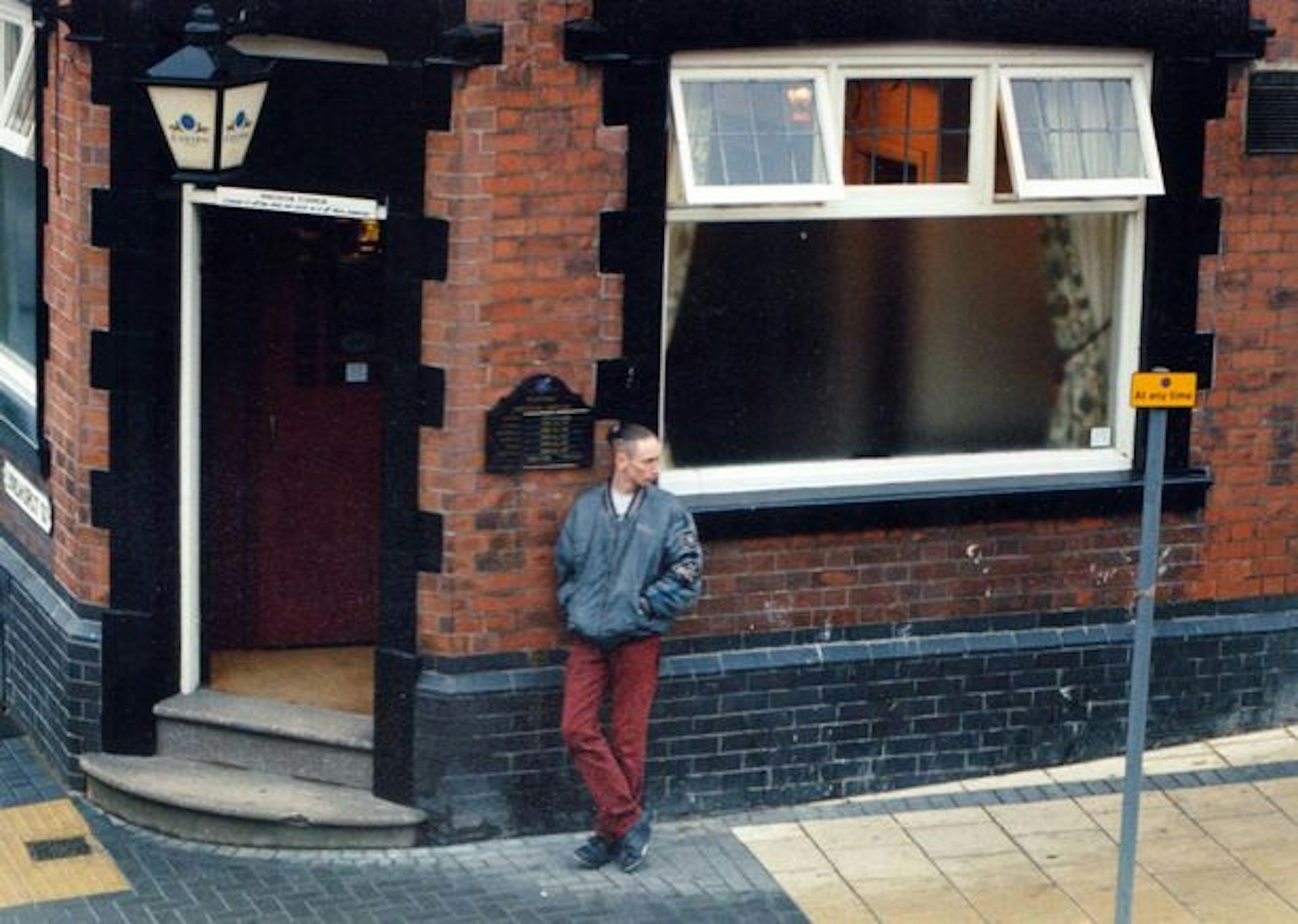

Among those advocating for a different approach is Neil Woods, a former undercover drugs detective who used to infiltrate Britain’s most dangerous drug gangs from 1993 to 2007. He spent his days befriending street heroin dealers before taking on their gangster bosses. But now, he forms part of the board at LEAP, campaigning for evidence-based drug policy.

So what led this dedicated law enforcement officer to turn his back on the War On Drugs? “Like many officers, I was initially very invested in what I was doing, with long days undercover in the community,” Woods tells Huck. “But over time, I started to question whether we were actually trampling on the lives of people who needed help, instead of supporting them.”

Woods explains that there was one big operation in 2007 where he spent seven months gathering evidence on six key members of the notorious ‘Burger Bar’ gang, who had brutally taken over the lucrative Northampton drug trade. As Birmingham’s main street gang, their violence spanned two decades, and intelligence showed they were responsible for several unsolved murders, firearms trafficking, and even mistakenly killing two innocent women on the street with a MAC-10 submachine gun.

He slowly built up a relationship with two local heroin user dealers, finally getting close enough to secure an introduction to their suppliers, so the police could obtain evidence for a drug supply conviction. “There were – literally – hundreds of officers involved in this operation, which meant we identified 96 members of the group, many of whom were later convicted despite being vulnerable,” Woods says. “And, after all that effort, the intelligence officer told me that we’d disrupted the town’s heroin trade for an entire two hours. It takes four hours for a problematic heroin user’s withdrawal to kick in, so what was the point?”

Neil Woods undercover in the 1990s

Five years later, Woods decided to leave the police, swayed by growing evidence that the police’s role in enforcing drug prohibition was having a negative impact on societal and individual wellbeing. “Police are good at catching drug users and dealers,” he says. “You double their budget and there will be double the convictions. But unfortunately, this doesn’t ever reduce the size of the market. Every time you take out an organised crime group, another is eagerly waiting to step into its place.”

Arfon Jones, who served as North Wales’ Police and Crime Commissioner from 2016 to 2021, is another long-serving police officer who turned his back on prohibition and subsequently joined LEAP. Jones spent three decades in the police, before retiring in 2008 at the rank of inspector. Since then, he’s worked as a Plaid Cymru county councillor in Wrexham, run for Parliament in the area, and controversially proposed that prisoners should receive free cannabis in a bid to quell violence and spice addiction.

Jones first read about drug decriminalisation in 2007, when the retired Chief Constable of North Wales Police wrote a paper on the topic. “[The Chief Constable] argued that the decriminalisation of drugs is inevitable, even suggesting that repealing the MDA would destroy a major source of organised crime,” recounts Jones. “This idea certainly raised a few eyebrows at the time, and I remember thinking it was a little unusual.”

“But gradually, I came to reflect on the topic and it became clearer that decriminalisation could reduce the harms of illicit drugs, whether it’s heroin users shoplifting to pay the vast street prices, or teenagers inadvertently consuming cocaine cut with dangerous additives,” he explains.

Jones says that county lines drug supply has led to violence in several Welsh market and coastal towns, with vulnerable young people often forced to transport or sell crack and heroin. But after researching the legalisation of cannabis in Uruguay, he learned there’s been a significant drop in violence now that the drug’s no longer exclusively in criminal hands.

He adds: “There are Heroin Assisted Treatment Schemes across the UK, including in Teesside. And it’s positive that researchers are evaluating whether this can reduce drug-related harm to individuals and the community.”

But are progressives like Jones wasting their time trying to change long-serving police officers’ deeply-entrenched views? “As leaders, Police and Crime Commissioners have the ability to gradually drive a progressive culture shift in the organisation, whereby users and dealers aren’t simply viewed as perpetrators of crime – they’re victims in need of support, tolerance and compassion too,” he responds.

Arfon Jones

“I’ve run training events on the importance of a public health approach to drug use and supply, and afterwards, I’ve had experienced officers tell me that it’s completely changed how they approach the matter,” he explains. Now, Jones supports drug regulation, which goes a step further than decriminalisation in advocating for a state-owned, legalised drug market.

Suzanne Sharkey, a former constable and undercover operative and the current co-executive director of LEAP, similarly believes that a more compassionate approach needs to be adopted. Like Woods, she left policing because she was concerned the organisation was failing to help vulnerable people in need of support.

“In reality, I wasn’t locking up career criminals or really bad people: instead, I was imprisoning people that were ill and needed treatment,” reflects Sharkey. “I do feel quite shameful about the work I did, as the negative consequences outweighed the benefits. Drug policy is a failure, it’s done more harm than good.”

“As soon as you get one dealer off the street, you’ve got somebody waiting to step into their shoes – it’s a business opportunity for somebody else. We need to legally regulate the drug trade because our current policies destroy families,” she explains. Sharkey believes that regulation would take drugs out of criminal hands and place them under the control of doctors, pharmacists and licensed retailers, which would, in turn, reduce the impact of organised crime.

But while international organised crime continues to grow in power and influence, Sharkey, Jones, Woods and their colleagues at LEAP urge law enforcement to be honest and acknowledge this global crisis. As Woods tells police: “It’s not your job to defend a policy that is eroding the functionality and credibility of your institution. Now is the time for you to treat drug addiction and supply as the public health crisis it is.”

Follow Rebecca Tidy on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.