The TikTok student activists occupying Manchester Uni

- Text by Joe Goodman

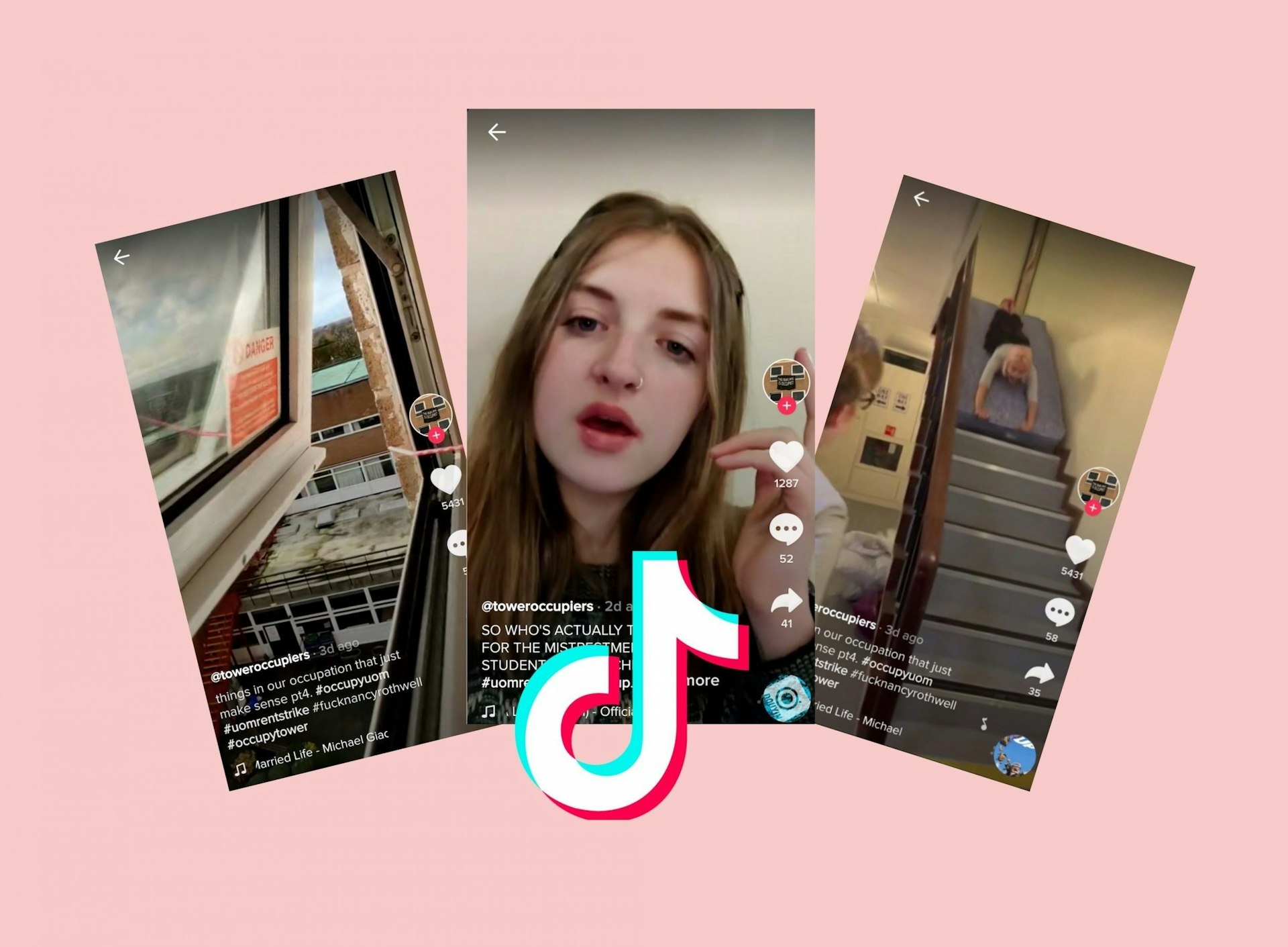

- Photography by courtesy @toweroccupiers via TikTok

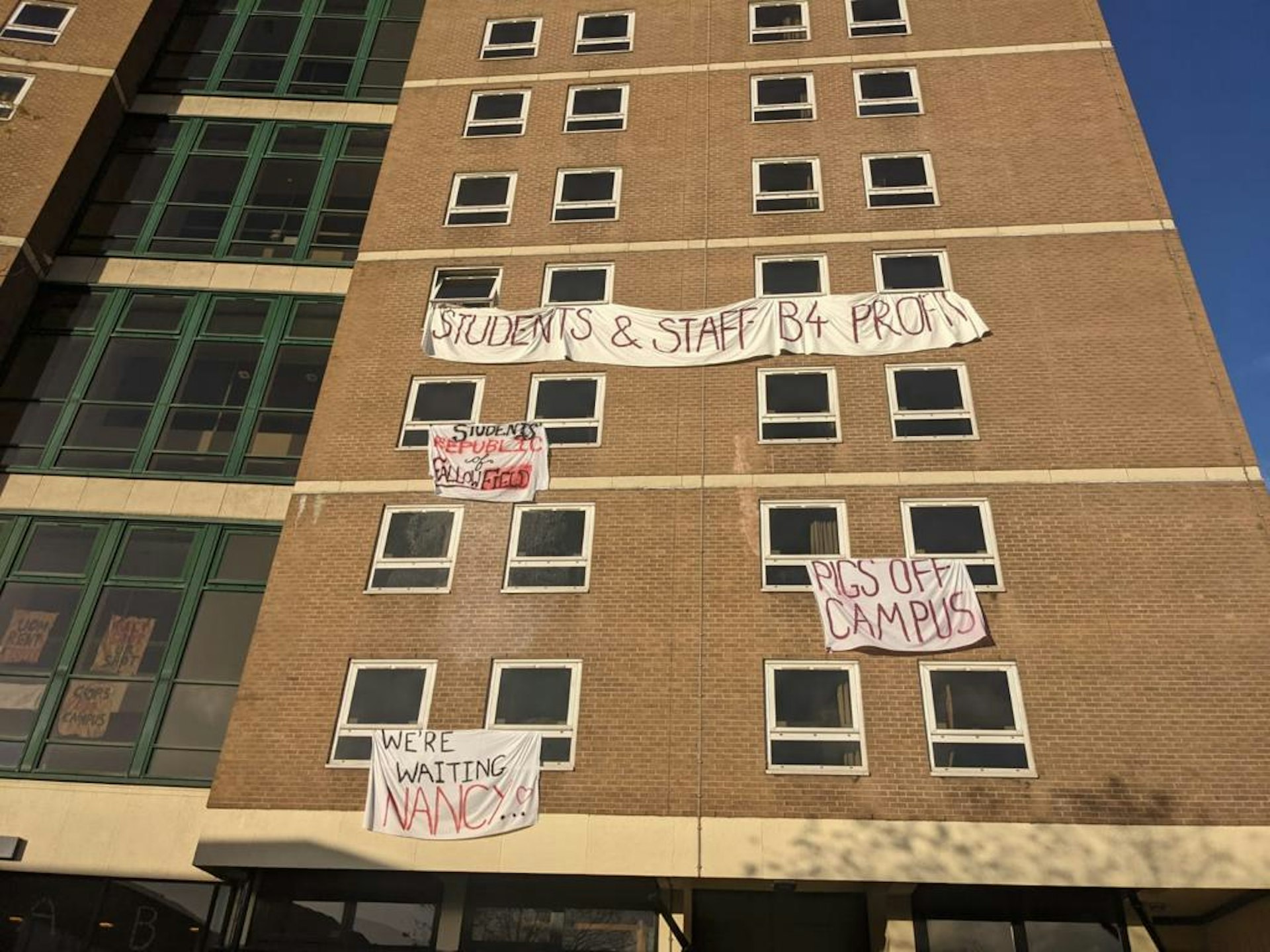

At around 10:30 am last Thursday (12 November), nine University of Manchester students entered Owens Park Tower, a hall of residence located in Fallowfield, padlocked the doors behind them and settled in. The students – mostly first-years aged 18 or 19 – were following in a long tradition of student protest by occupation and responding, in large part, to their university’s abysmal handling of COVID-19.

While their occupation has garnered widespread coverage, the students themselves have been broadcasting the everyday reality of their demonstration to a global audience via their TikTok account, @toweroccupiers. In one video that has now been watched almost 24,000 times, a student parodies Dolly Parton’s ‘Jolene’, singing “Nancy, Nancy, we’re begging of you please don’t take nine grand” – a reference to the University’s vice-chancellor, Nancy Rothwell.

In another video watched 68,000 times, the students give a tour of their occupation, which sees them drinking tea from Tupperware “because we forgot mugs”, while a later tour sees them doing a “two am mattress dive” down the building’s stairs.

“We set it up as a bit of a joke,” says Izzy Smitherman, a first-year English Lit and French student who runs the TikTok account. “We were thinking students at this University and our friends would watch them, but I don’t think we realised the spread it would get.”

The occupation comes in the wake of students being forced to self-isolate in September within just two weeks of returning to University. Earlier this month, tensions reached fever pitch when, overnight, without warning nor explanation, the University erected fences around the city’s Fallowfield halls of residence, which students subsequently tore down in protest.

For those occupying the tower, the message couldn’t be clearer: enough is enough. After dropping their banners from the tower’s windows last Thursday (12 November), the students went online to declare their demands, which include a 40 per cent rent reduction until face-to-face teaching resumes, greater support for students including safety, maintenance and mental health provision and no further staff redundancies.

That evening, a spontaneous Zoom conference from the occupation invited speeches from NUS president Larissa Kennedy, author Grace Blakeley and Jeremy Corbyn ex-frontbencher, Laura Pidcock. A week later, with the occupation ongoing, university management offered a 20 per cent rent reduction for the rest of term, which the rent strikers have calculated as a true five per cent rent reduction. They declined.

Meanwhile, the campaign – and the TikTok account – continues to grow. In under a week, the account has accrued almost two million views and more than 17,600 followers (on Instagram, the number is significantly less, at 4000 followers). Smitherman thinks TikTok’s informality could be helping them to reach new audiences. The key, she says, is not to be formulaic: “People listen to other people their age quite a lot and students aren’t tuning into Sky News or BBC news as much anymore,” she says.

“Seeing on TikTok that there are other people your age starting to engage with what is actually happening at uni, and starting to draw comparisons between our living conditions and the amount of money that the University is making off us, is politicising people.”

Matt Myers, author of Student Revolt (Pluto Press) – an oral history of the 2010 student protest movement – sees this as a departure from previous movements. “Anonymisation was a very important aspect of social protest in 2010,” says Myers. “The rejection of leadership or the suspicion of leadership – whether that be student union, national student union or political parties – was one of the defining features of 2010.”

By bringing audiences backstage – or inside of the occupation – TikTok, in particular, with its proclivity for humour, punctuates the formality of traditional messaging. “Putting a face to a name, or showing the individuals’ faces behind a movement, can humanise in a way that anonymisation can’t,” explains Myers.

“The reach we’re getting is way bigger than anything the University can do,” says Ben McGowan, a first-year politics and sociology student who is also occupying Owens Park Tower. This should come as little surprise, given that 60 per cent of TikTok’s two billion downloads have come from Gen Z users, and among this generation are the almost half a million students who will be starting university in the UK next year.

McGowan thinks the @toweroccupiers account is helping them to reach “the core demographic that the University cares about, in particular right now, is the Year 13’s that are applying to University”.

the tiktok about the vice chancellor of UoM’s response to the rent strike has 370,000 views, the @rentstrikeUoM tiktok account has 16,000 followers and their most viewed videos have just under 400,000 views- think it’s apt to describe this as a massive L for UoM PR department

— eli 📕 (@elihxrris) November 14, 2020

Both McGowan and Smitherman think that the University underestimates just how potent a tool TikTok is in their movement. A TikTok of the occupiers being denied a pizza delivery by campus security has been viewed almost half a million times and has over a thousand comments. One comment says simply: “*withdraws Manchester uni application plans*” and has been liked 3861 times, while another reads, “Uni, but make it ✨prison✨”.

“The amount of Year 13’s we get commenting saying: ‘I’m not going to go to the University of Manchester next year, I’m reconsidering my application’ is a lot,” says McGowan.

The University of Manchester’s online presence encompasses Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, but is yet to stretch to TikTok. In response to the depiction of the institution on TikTok, a University of Manchester spokesperson said: “We monitor popular social media sites to measure sentiment and views of our community, including sites popular with student audiences, but we do not monitor individual social media profiles of students. The University is fully committed to freedom of expression, whether that is communicated online or offline.”

The establishment being overwhelmed by nascent technology is not a new story. As Myers recollects, in 2010, the policing of protests at Millbank ran up against trouble when they grossly underestimated the size of the incoming crowd. “The police calculated how many people would be coming on the demonstration by the usual means of contacting student unions and finding out how many buses had been booked.”

“Whereas social media, through the diffuse of Twitter and the blogosphere, meant the numbers had gone far higher than traditional parameters,” says Myers. As a result, Millbank, the Conservative Party’s HQ, was briefly occupied and the student-tuition fees campaign was galvanised nationwide.

“I think in some ways, tuition fees going up was the beginning of education and universities being run like businesses, and students just being used for profit,” observes Smitherman.

But the world in 2020 is a far cry from just a decade ago. “In 2010, social media was very limited, whereas now it is the main form of communication between students,” she adds. While COVID-19 might deter 50,000 students from marching through London, Smitherman believes TikTok could provide a compelling alternative for organisers.

“On our TikTok, we’ve had hundreds of thousands of views and we’re really reaching a wider audience of people our age group and younger generations as well,” Smitherman says. “Obviously Millbank was on a lot larger scale, but who knows how this will grow.”

Follow Joe Goodman on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.