How documentary photography transforms the way we see

- Text by Miss Rosen

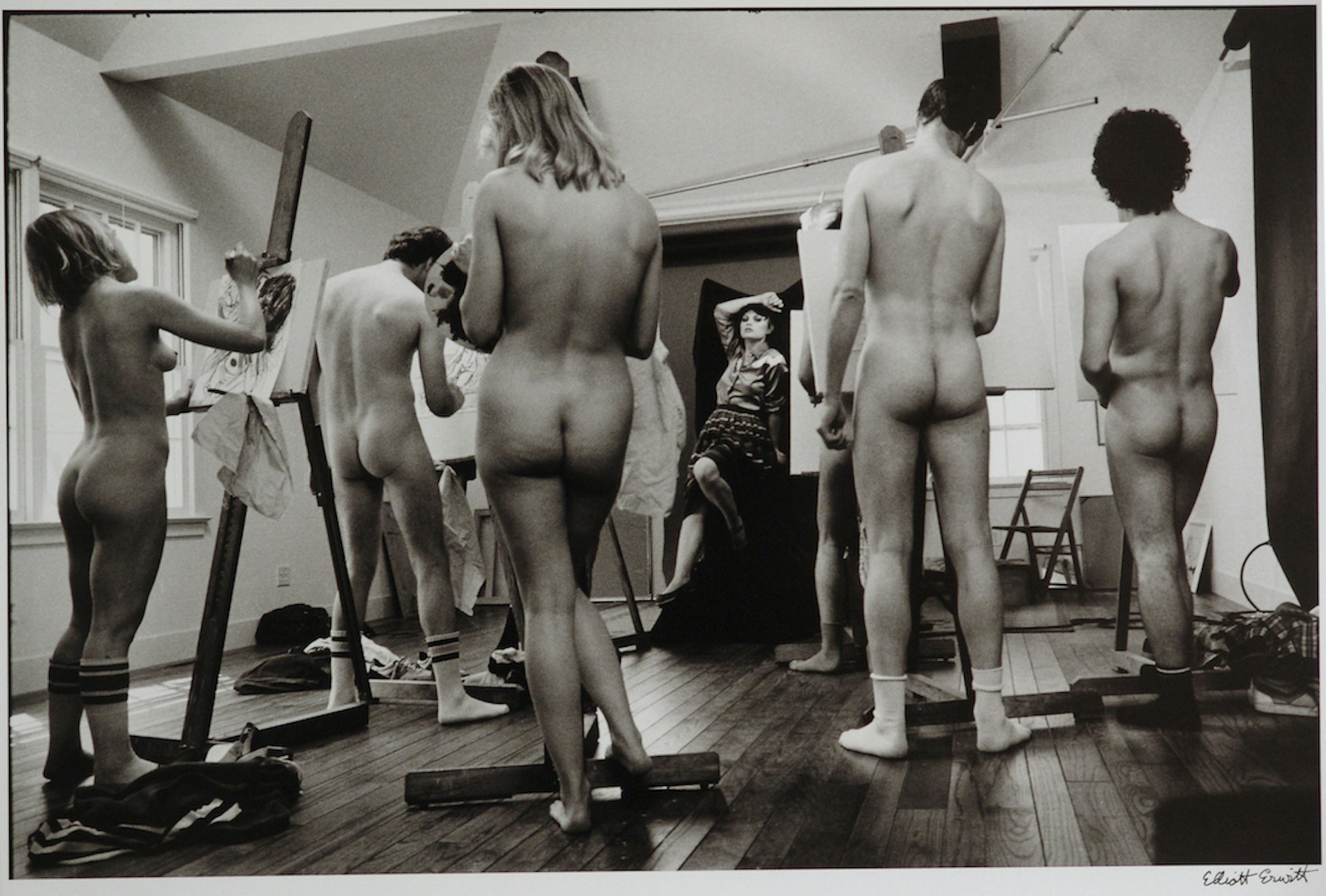

- Photography by Elliott Erwitt (main image), all photography courtesy Alex Webb/Magnum Photo

The documentary photograph, both art and artefact, occupies a singular place in the historical record. It acts as testimony, bearing witness to those whose voices might otherwise go unheard, and it can be used as a form of activism to change the world.

A new exhibition, For the Record, brings together the work of some 35 photographers whose innovative approaches have redefined not just the genre but also the medium writ large. From Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York to Danny Lyon’s Bikeriders, to Larry Clark’s Tulsa, and Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang, the exhibition chronicles the role of documentary photography in shaping the way we see and think about the times in which we live.

By combining classical and contemporary approaches, the exhibition explores the ever-evolving language of photography and the ways in which it simultaneous straddles the realms of reportage and fine art. As 17th-century clergyman Thomas Fuller famously said, “Seeing is believing, but feeling is the truth” — a sentiment that captures documentary photography’s extraordinary ability to communicate the emotional impact of people, places, and events.

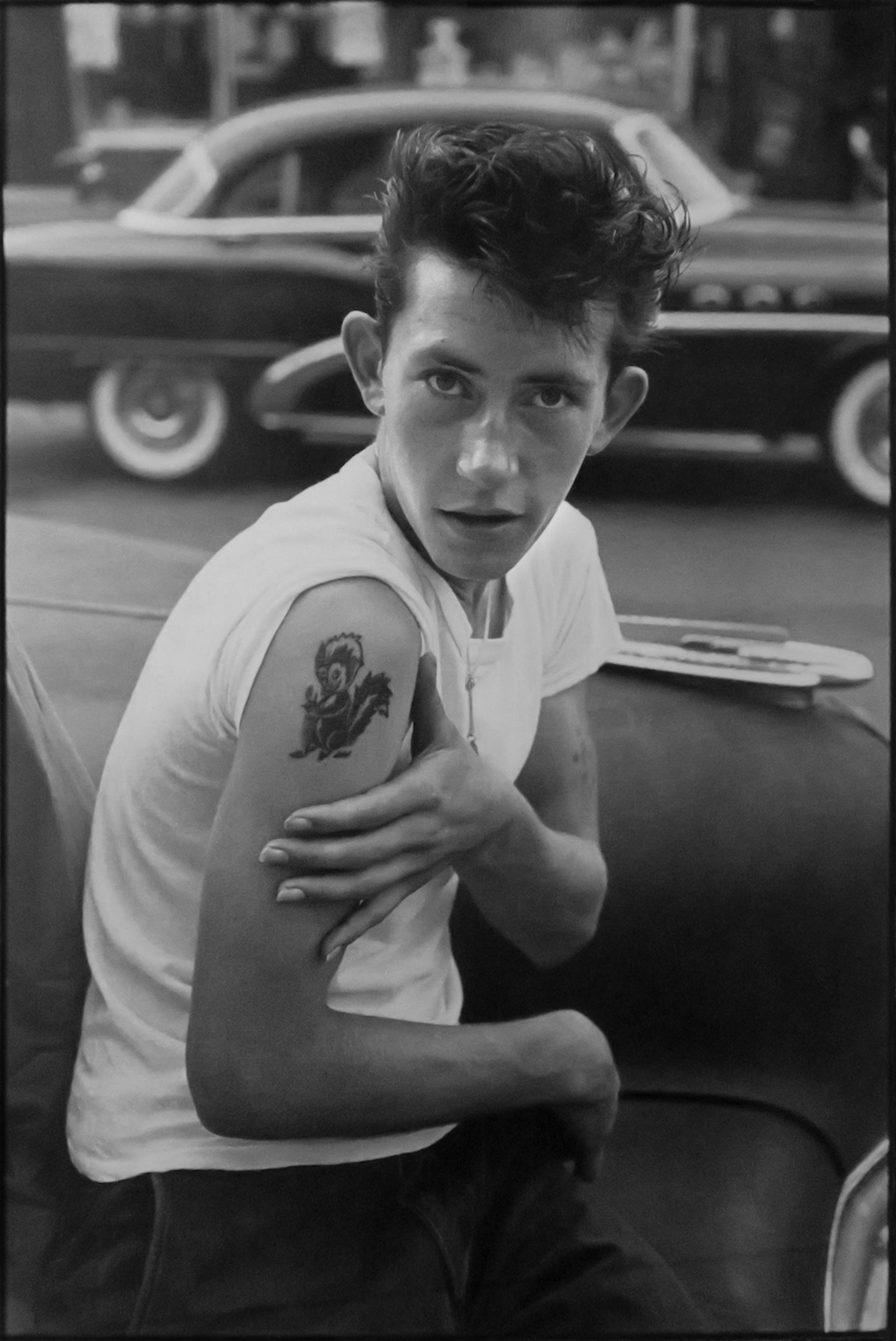

Untitled, (Boy Showing Tattoo on Arm) from Brooklyn Gang, 1959, gelatin silver print © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Haiti, 1979, Alex Webb

At a time when notions of “truth” have been undermined by conspiracy theory and profound distrust, documentary photography offers a moment of respite in the rhetorical storm. For Magnum Photos member Alex Webb, adopting an exploratory approach instead of fact-finding is paramount.

“I’m interested in the intuitive journey, the discovery of the surprising or unexpected, not the preconceived notion,” Webb says. “I like photographs that take me somewhere I’ve never been before – both visually and emotionally – and images that open my eyes to something new, often something enigmatic. That’s why I tend to see my photographs as a series of questions, and not as answers.”

In 1975, long before the use of colour photography was accepted in professional circles, Webb had reached what he described as a “dead-end in my photography…. Somehow the work wasn’t going anywhere, wasn’t expansive enough.” After embarking on life-changing trips to Haiti and to the U.S.-Mexico border, Webb realised colour was an integral part of the story.

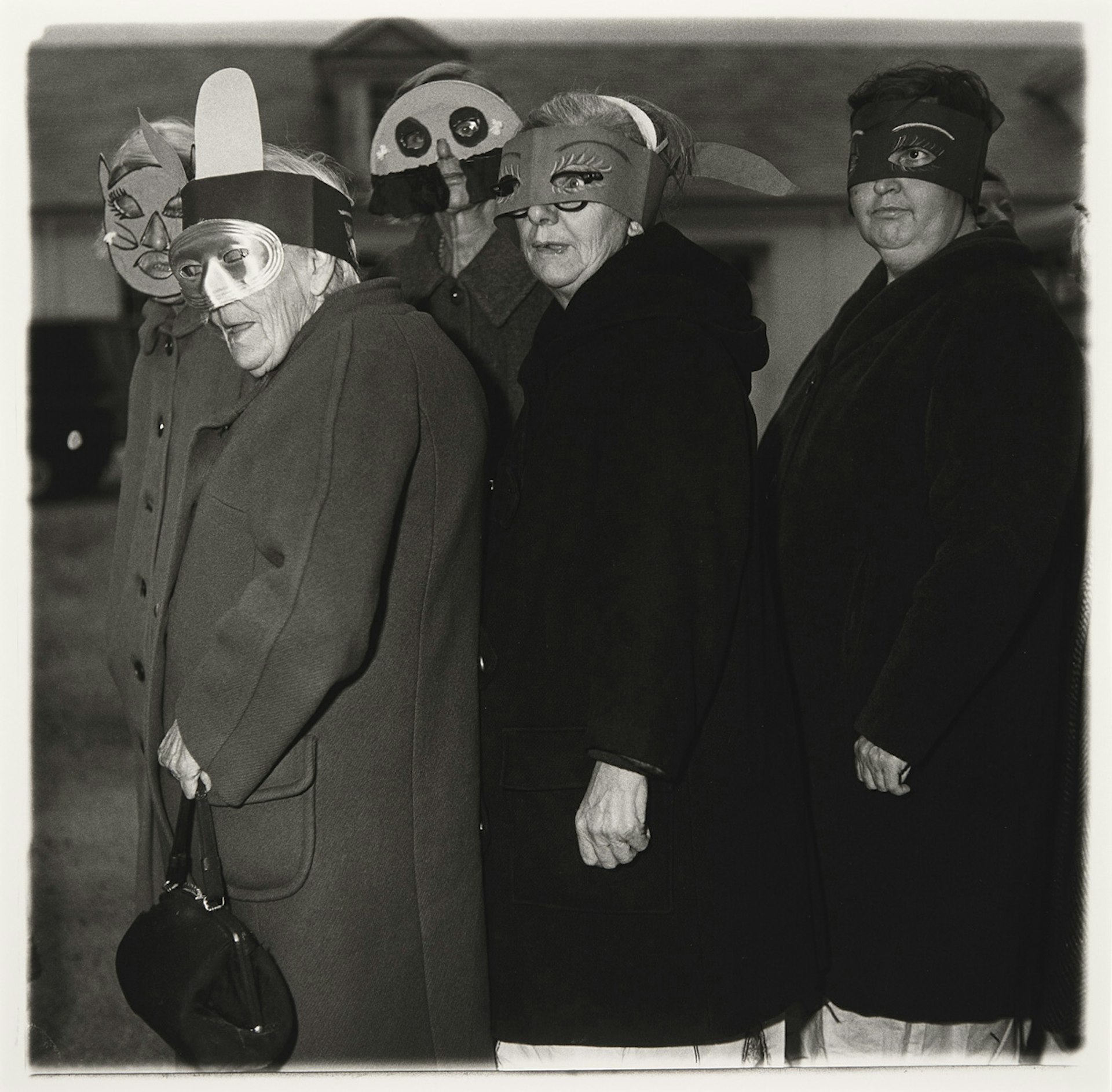

Untitled (14), 1970-71, gelatin silver print © The Estate of Diane Arbus

Mujer ángel, Desierto de Sonora, México, 1979, gelatin silver print © Graciela Iturbide

Like W. Eugene Smith, whose photo essays from 1950s-era LIFE Magazine are featured in the show, Webb adopts an immersive approach, believing that walking in the world with one’s camera is how photographers learn. “A slow, measured pace allows for a kind of gradual immersion into a world,” Webb says, “not too aggressive, not too intrusive, allowing me to slip slowly in and out of situations. Walking gives me a visceral sense of a place and its people.”

This understanding is shared by exhibiting artists like Robert Frank, whose influence on documentary photography spans generations. “I was drawn to The Americans for Frank’s edge and spontaneity,” Webb says. “I remain a believer in more exploratory and personal work – authored work that reflects a sense of discovery of the unexpected or of the unknown.”

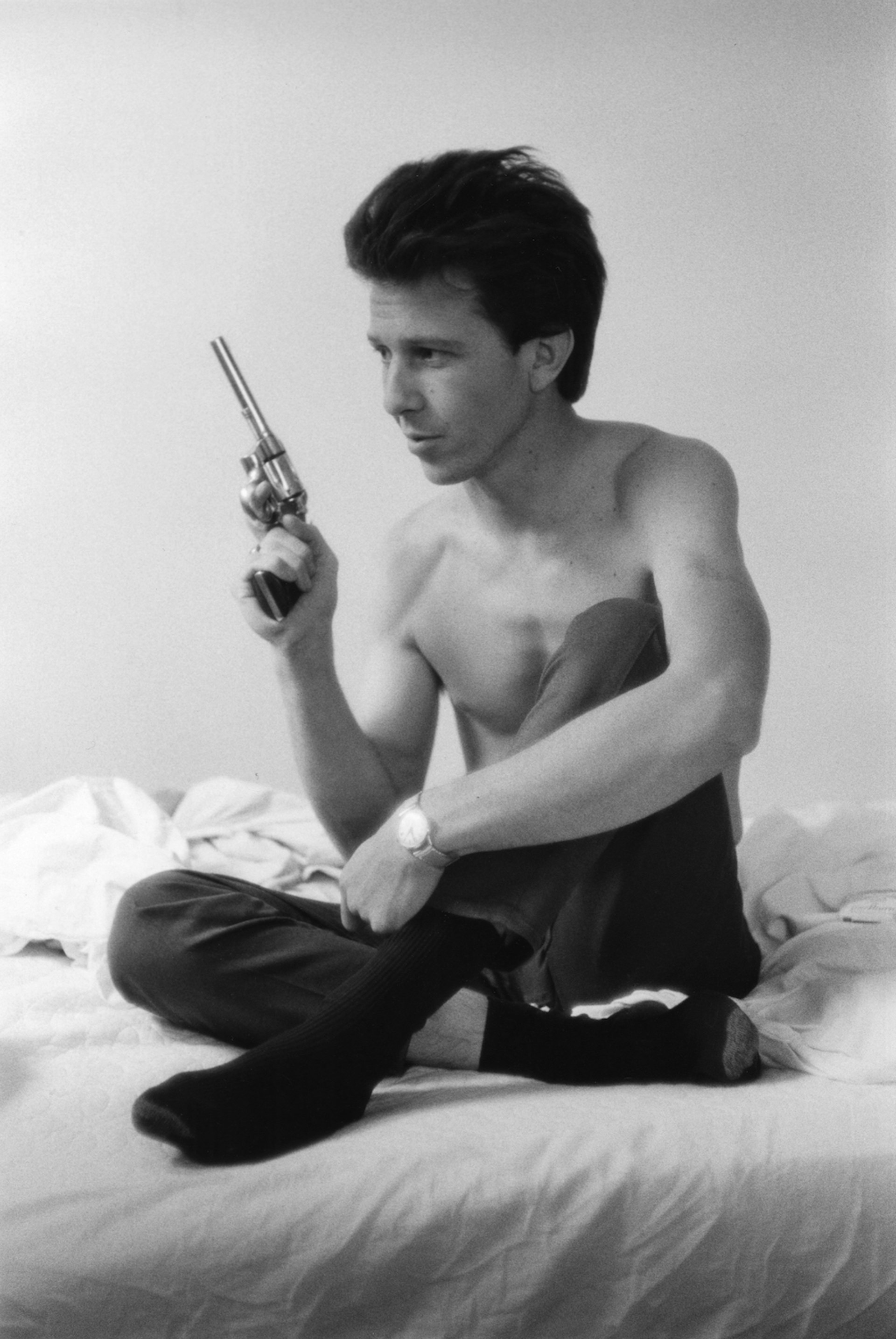

Billy Mann, from Tulsa, 1968, gelatin silver print © Larry Clark

Grenada Smoke, Alex Webb

London, 1951, gelatin silver print © The Estate of Ernst Haas/ Alexander Haas

For the Record is on view at Etherton Gallery in Tucson, AZ, through May 29, 2021.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.