A history of female gazes in African portraiture

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Ryerson Image Centre

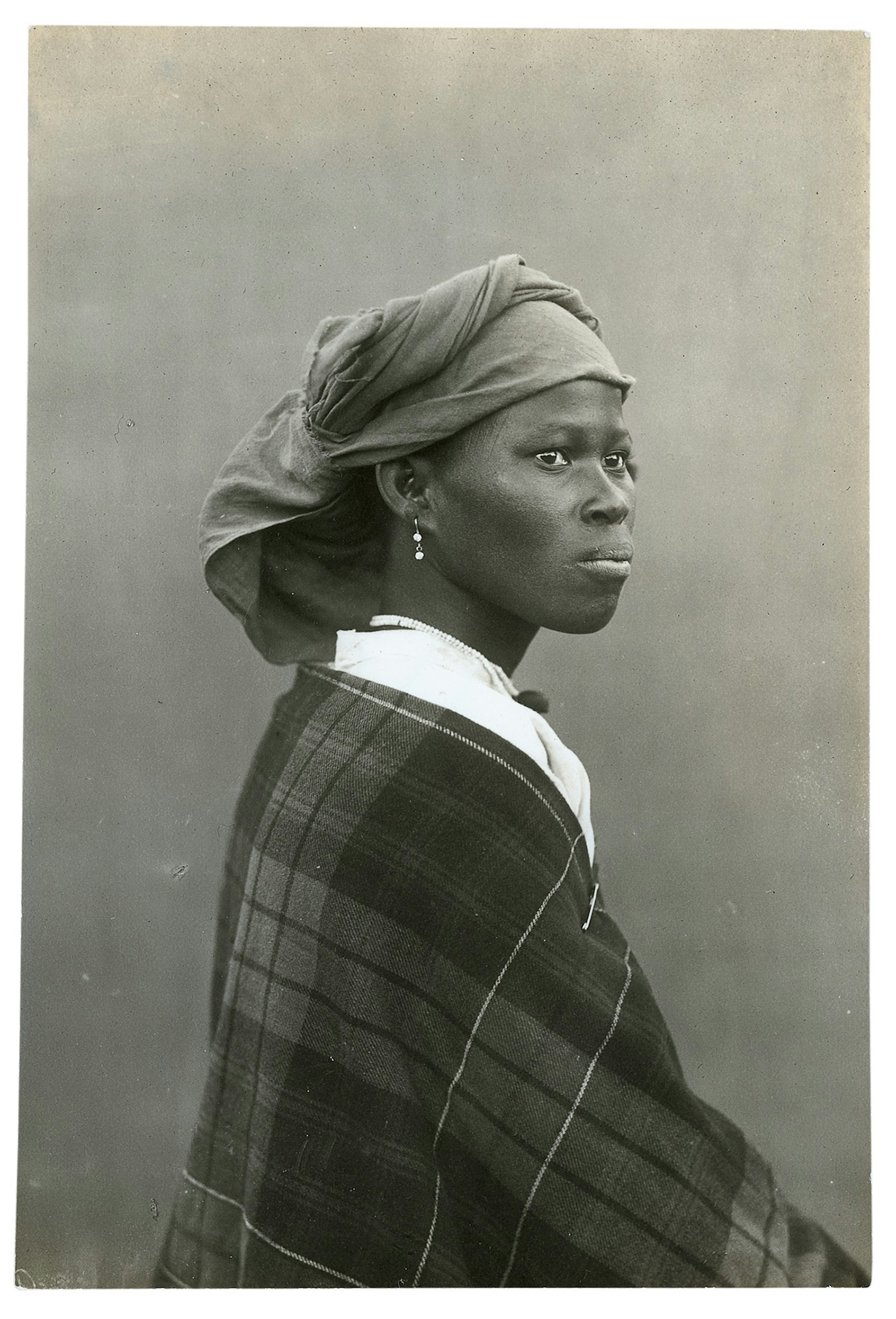

As European imperialists set forth to colonise the globe, they took everything they could – including images of indigenous peoples forced to pose for photographs against their will. They made, sold, and distributed images, often objectifying and fetishising the subjects. This is where our story begins.

A new exhibition, The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture, features more than 100 works drawn from The Walther Collection to trace the history of female agency in photographic form. Guest curated by Sandrine Collard, the show features works by Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, David Goldblatt, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Yto Barrada, Zanele Muholi, and Lebohang Kganye, exploring the role of women as both subject and photographer.

“When photography was invented, Europeans would travel, settle in colonies, open studios, and photograph the communities around them – most of the time without their consent,” says Gaelle Morel, Ryerson Image Centre Exhibitions Curator. “You had that forced gaze on people, and women in particular. This is a very specific way of photographing [by European men].”

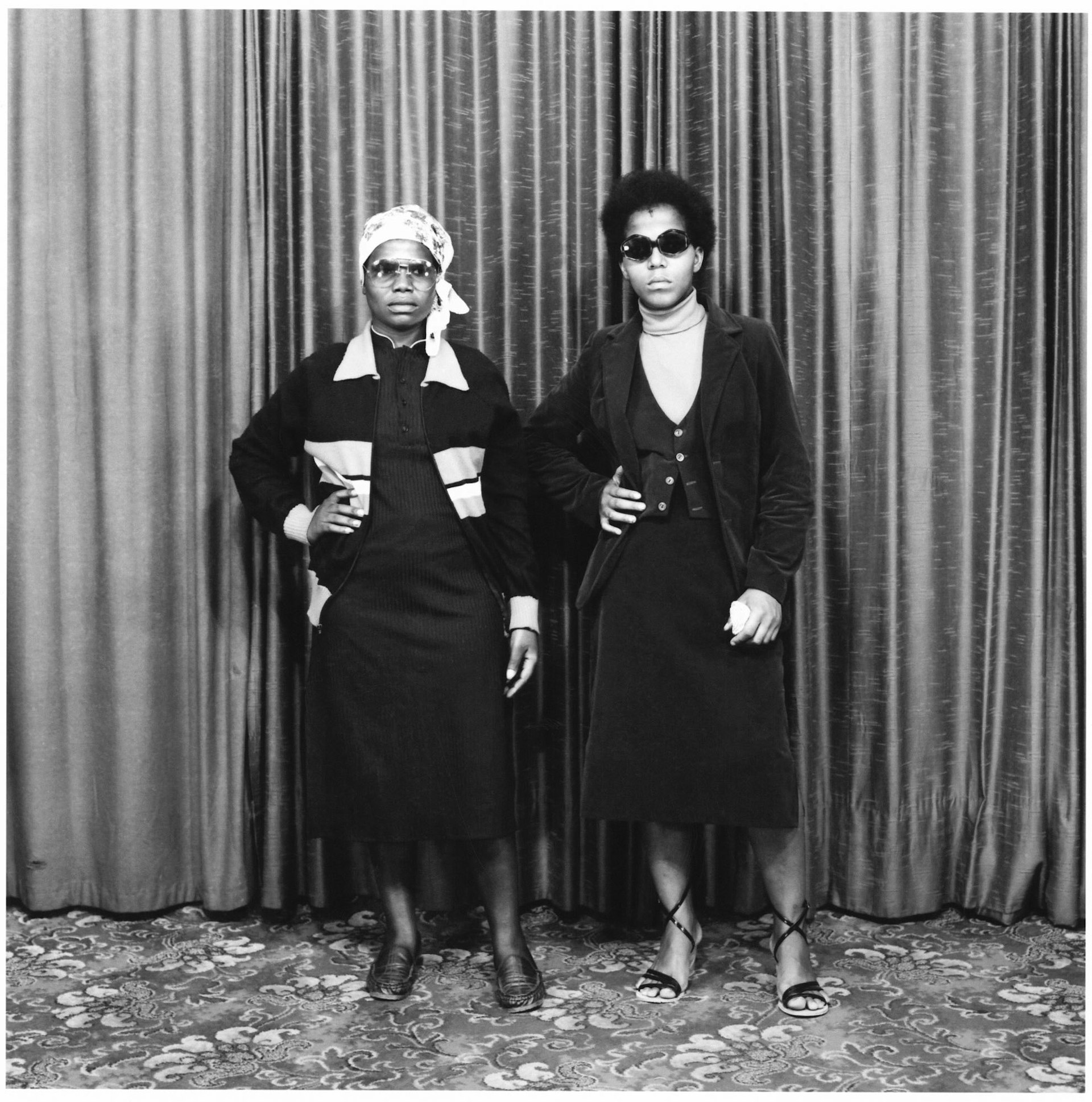

The Way She Looks showcases a selection of images where the sitters display acts of resistance, asserting their power in small but telling ways. “You have some traces they were in charge of their representation even though they did not choose to be represented,” Morel says. “The way you dress, clench your jaw, move your head, look, pose with your sister or mother – these are signs they had a little bit of agency.”

Alfred Martin Duggan- Cronin, Bakgatla, South Africa, early to mid 20th century. Courtesy of The Walther Collection, Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg, and The McGregor Museum, Kimberley

A. C. Gomes & Sons, Natives [sic] Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania, late 19th century. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

“Women have the power to say, ‘This is how I want to be photographed,’” Morel says, They styled themselves for the shoot, appearing with friends and family, or even alone, adopting postures, gestures, and expressions to communicate their identity to the world.

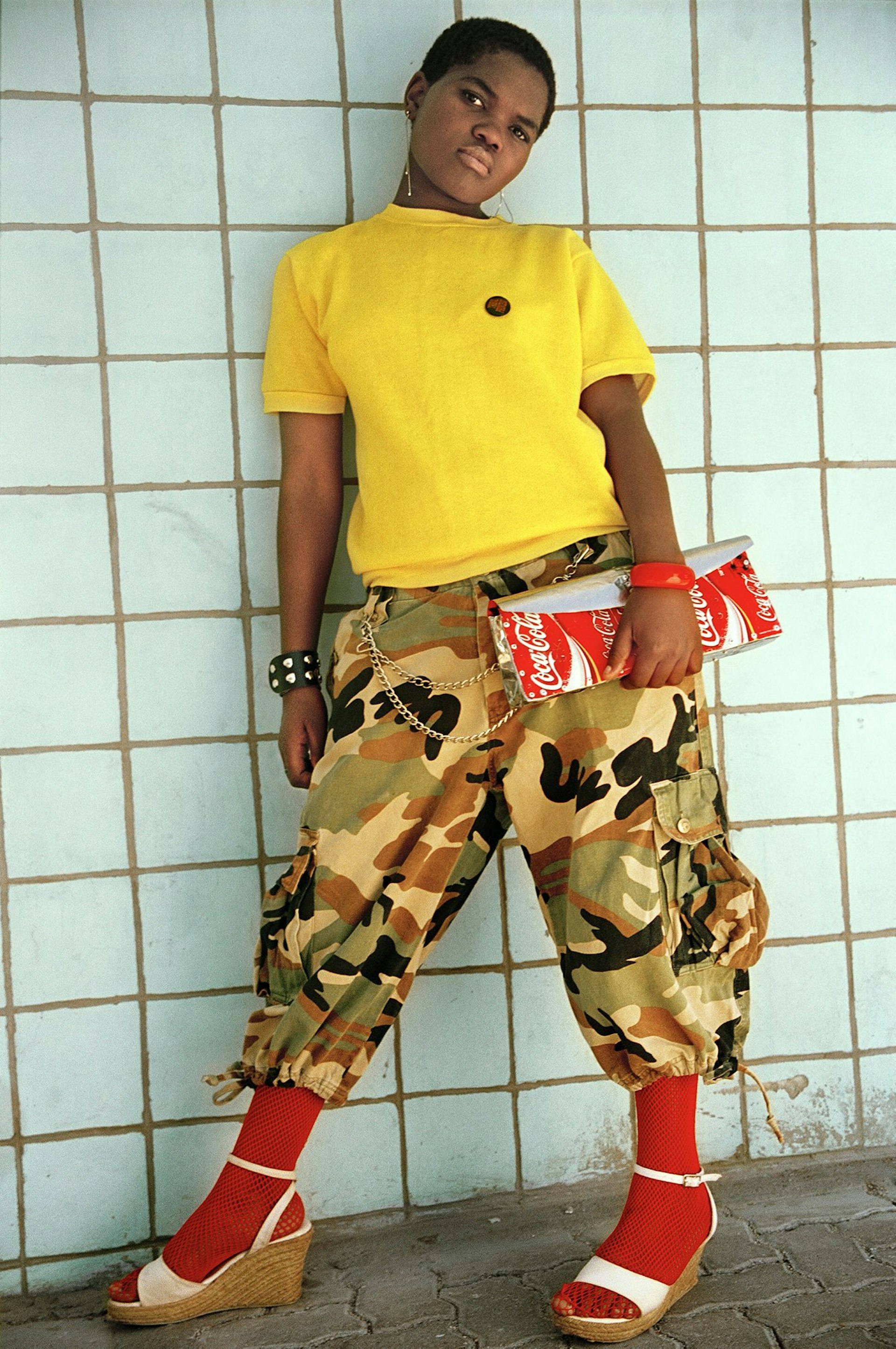

As the exhibition makes its way into the 21st century, it becomes much more inclusive with the addition of women photographers and non-gender conforming subjects. By centring queer and gender identities in a visual conversation about women’s perspectives, the exhibition allows the conversation to expand and grow.

“Everyone deserves to be represented in a dignified way. It hasn’t always been the case and it’s still not always the case,” Morel says. “The definition of gender can be stretched. It doesn’t matter how you were born, what matters is how you want to be perceived and identified… and how these communities can live and survive. You are pushing the conversation further when you open that door.”

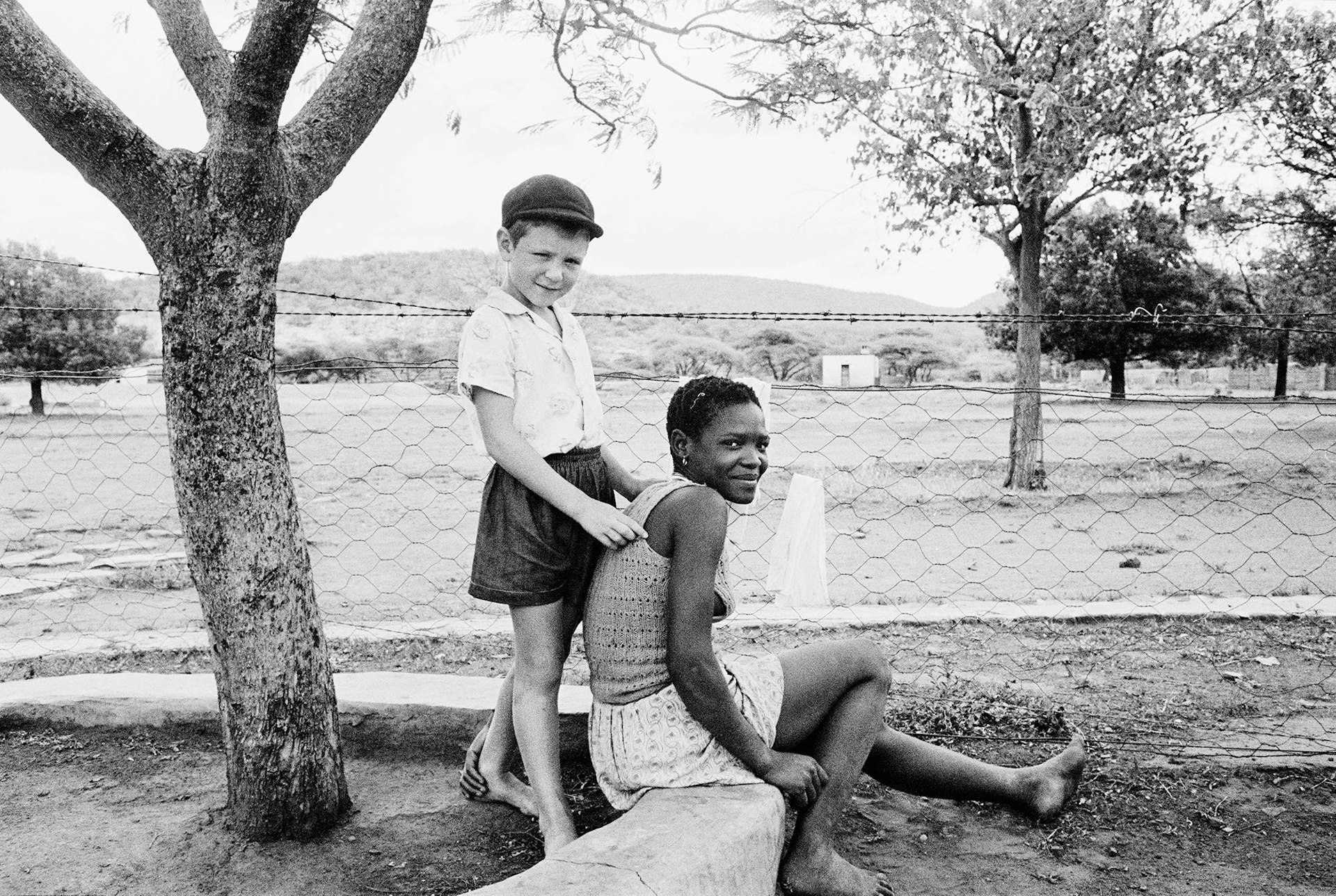

David Goldblatt, A Farmer’s Son with his Nursemaid, Heimweeberg, Nietverdiend, Western Transvaal, from the series Some Afrikaners Photographed, 1964. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

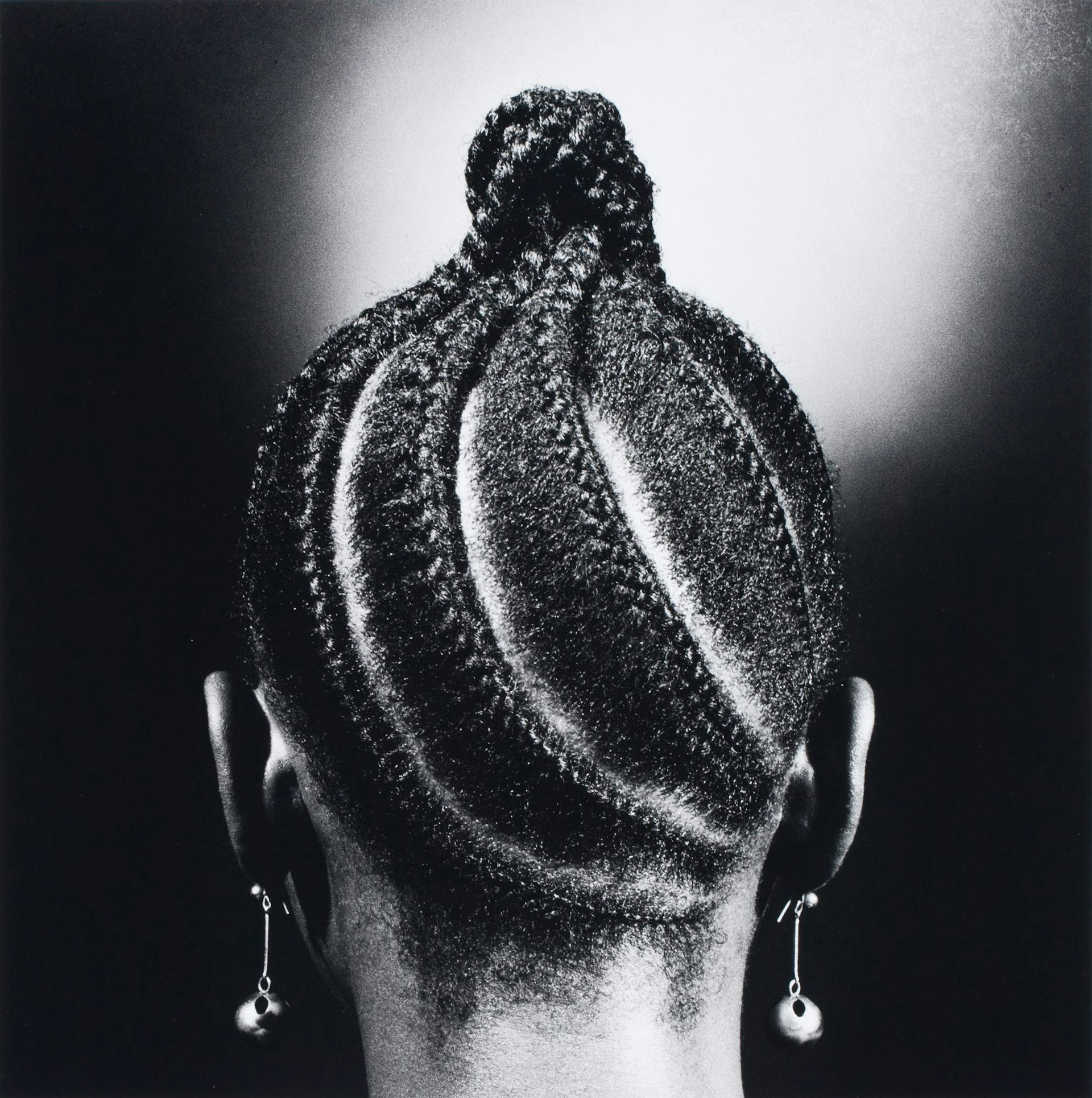

J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Suku Banana Onididi), from the series Hairstyles, 1974 (printed 2009). Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Galerie Magnin-A, Paris

S. J. Moodley, [Two women wearing Western attire], 1981. Courtesy of The Walther Collection

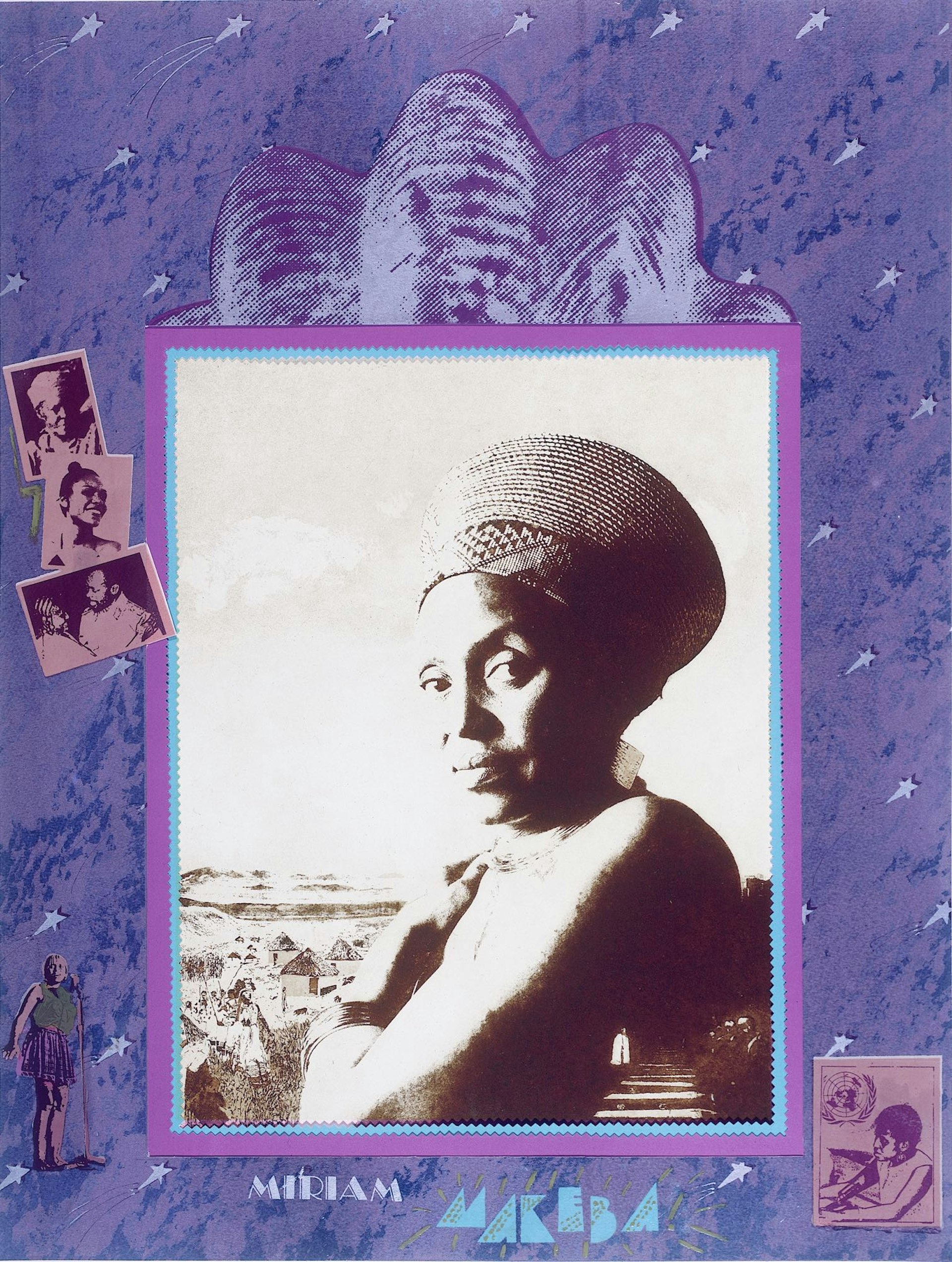

Sue Williamson, Miriam Makeba, from the series A Few South Africans, 1987. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko, Nonkululeko, from the series Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder, 2003. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Zanele Muholi, Miss D’Vine II, from the series Miss D’vine, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

abelo Mlangeni, Woman and City, from the series Big City, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and The Walther Collection

Jodi Bieber, Babalwa, from the series Real Beauty, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture is on view at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto, Canada, until December 8, 2019.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.