In my own words: Jim Goldberg, photo storyteller

- Text by Shelley Jones

- Photography by Jim Goldberg / Magnum Photos

“I grew up in New Haven, Connecticut. My brother and sisters were much older than me and went away to college so I was left home alone with my parents.

“At that time my father had a degenerative disease so it was like living with a disabled person and I think that, perhaps, created some sensitivity in me for people who were different, or the other. I didn’t really fit in to my family as much as they wanted me to and I think that lead me eventually to photography.

“A camera back then, and probably still now, was like having a calling card that let you into places that you normally wouldn’t go to, or to people you normally wouldn’t talk to.

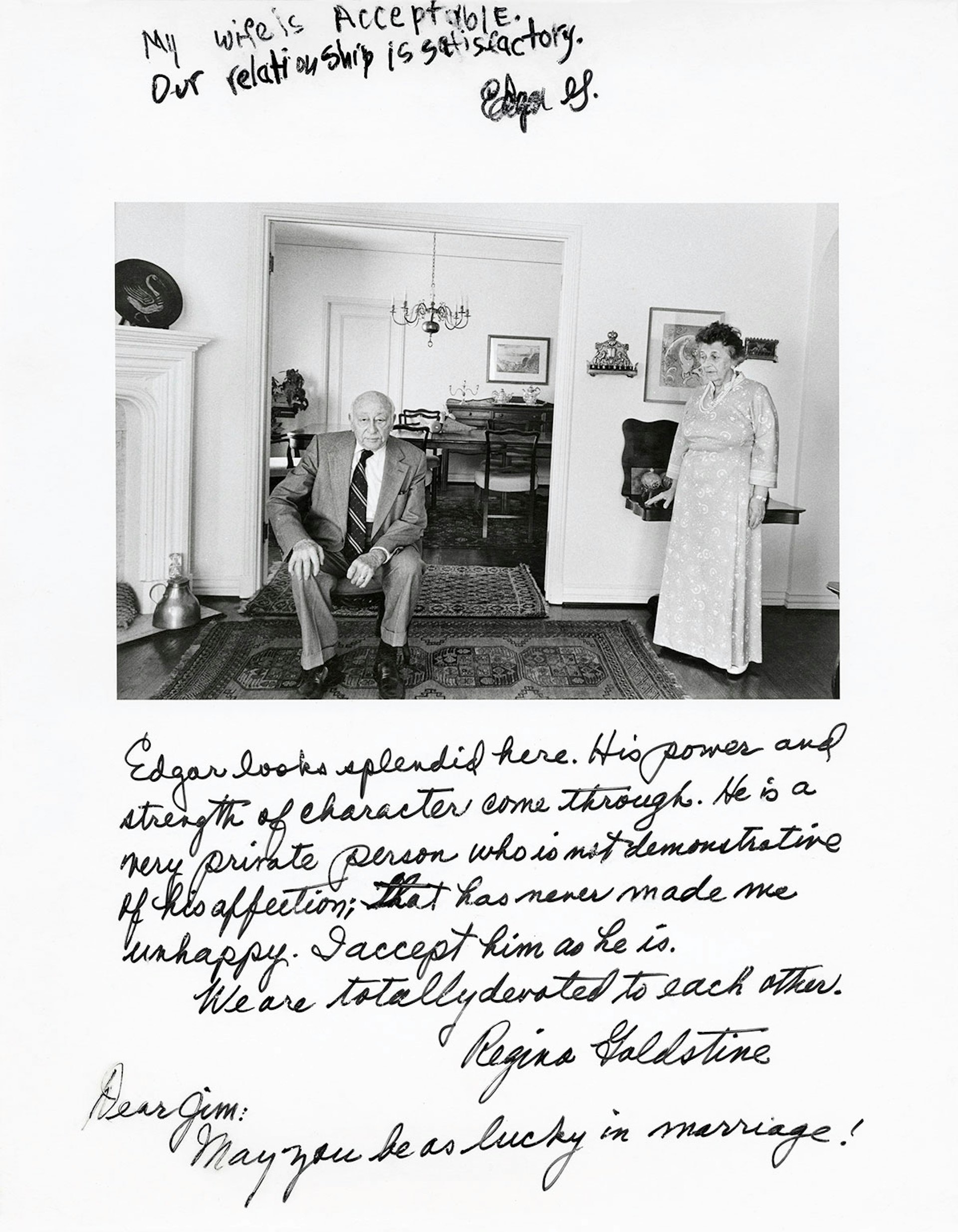

“I moved to San Francisco at the end of 1976 and probably soon thereafter I started going out on the street. Some of the people that I met were living in transient hotels, and they invited me into their homes and I photographed them.

“That was interesting to me. I was dealing with a group of people who I had very little contact with; they were poor, they were hidden, they were invisible people in these grimy rooms.

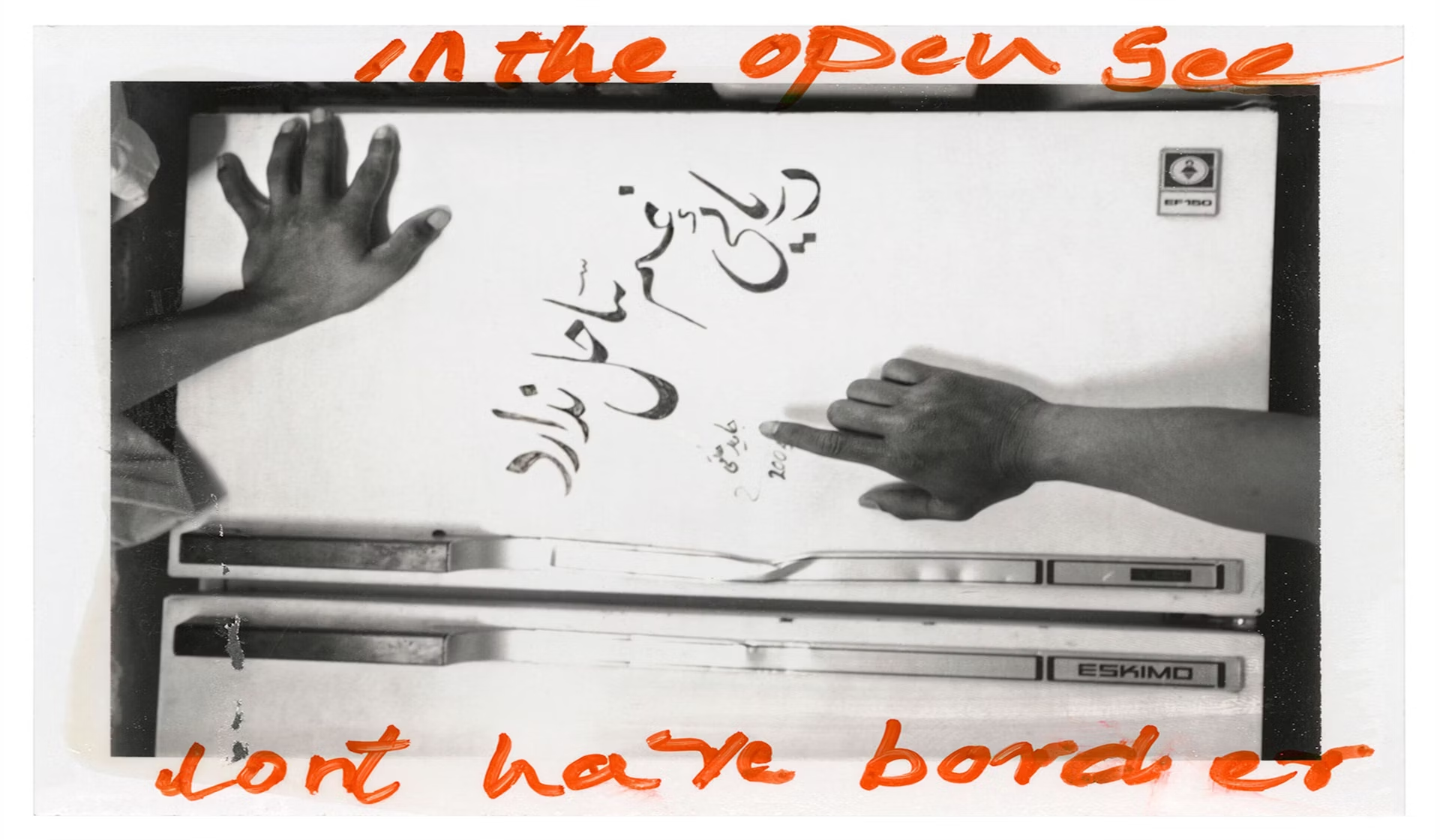

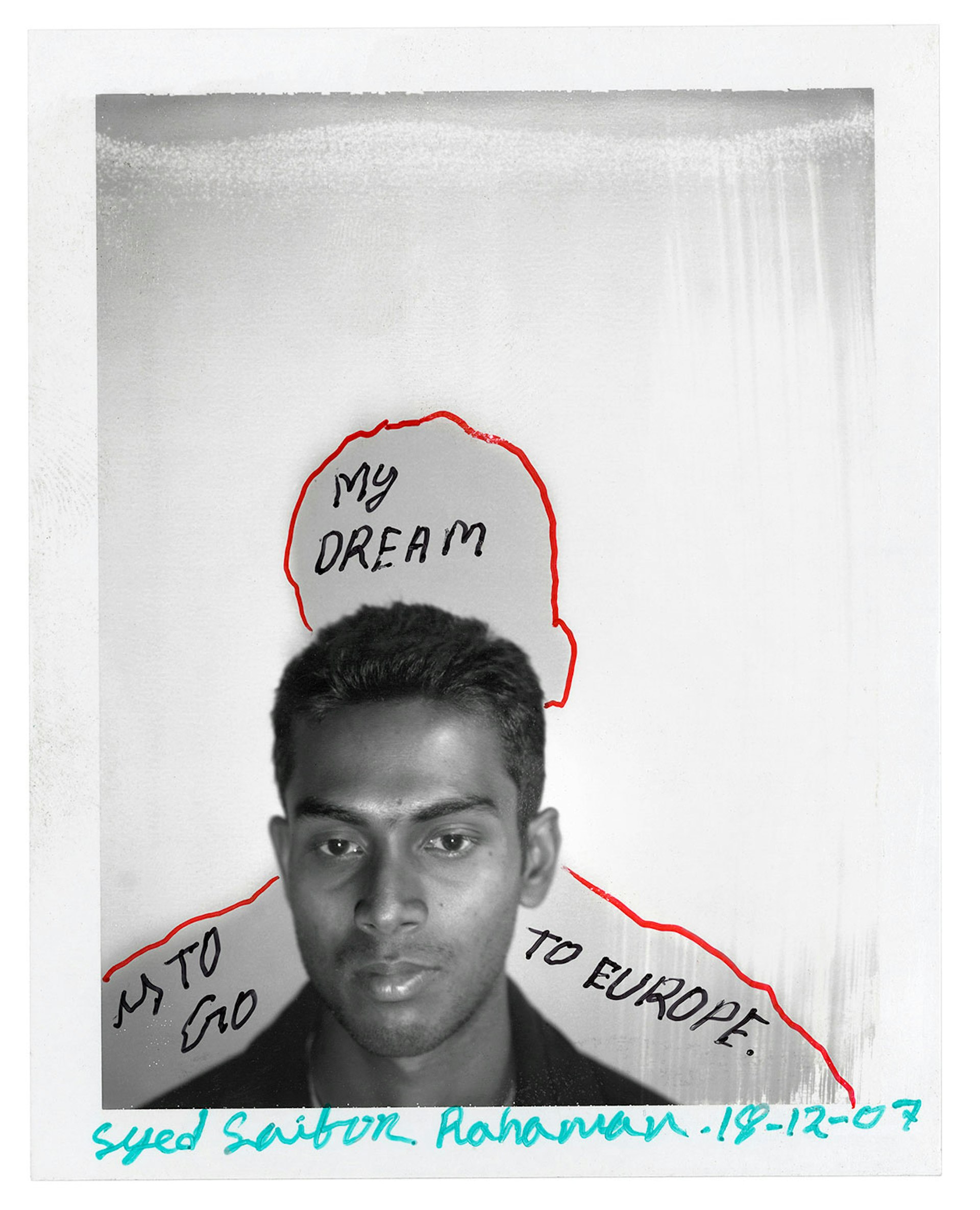

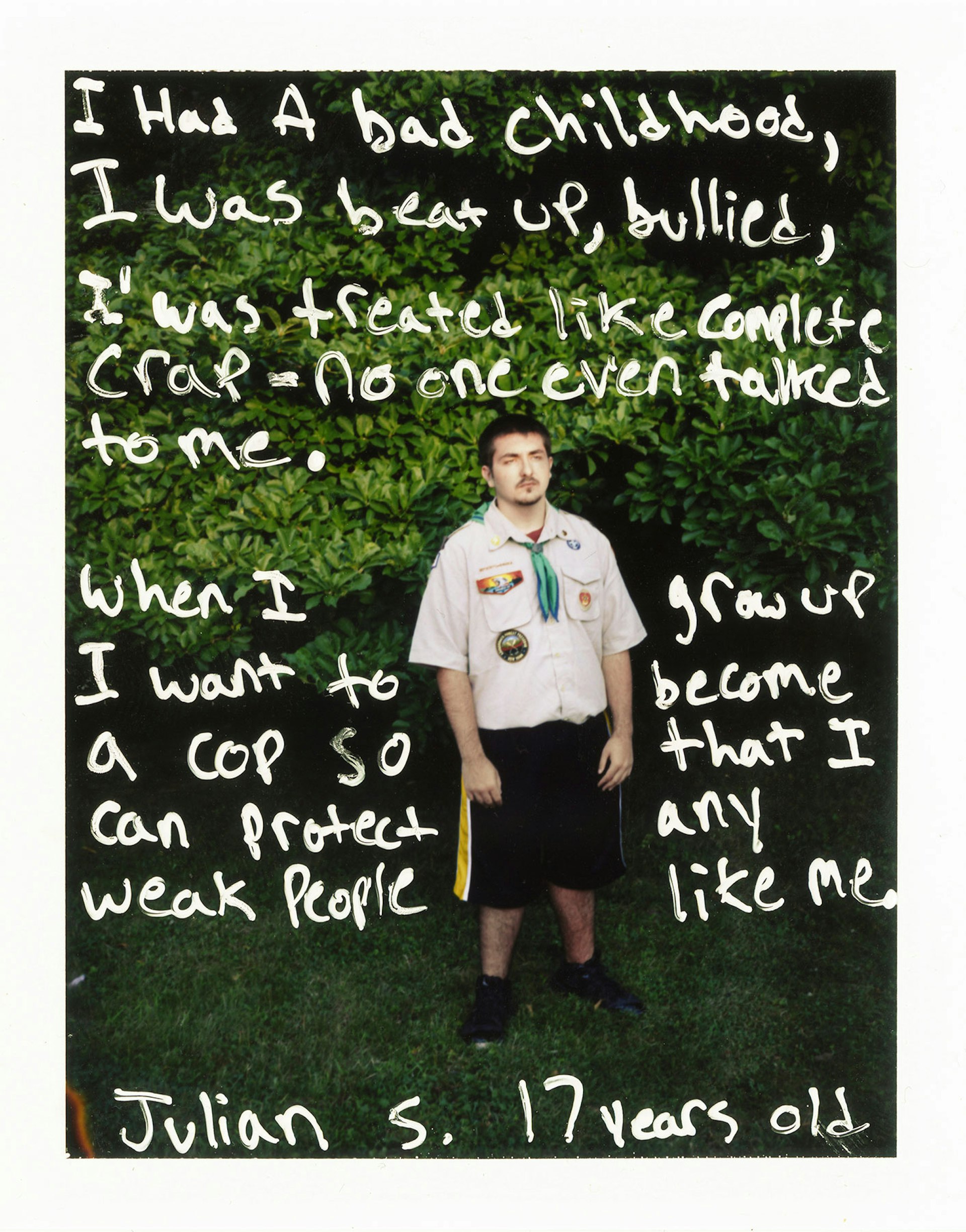

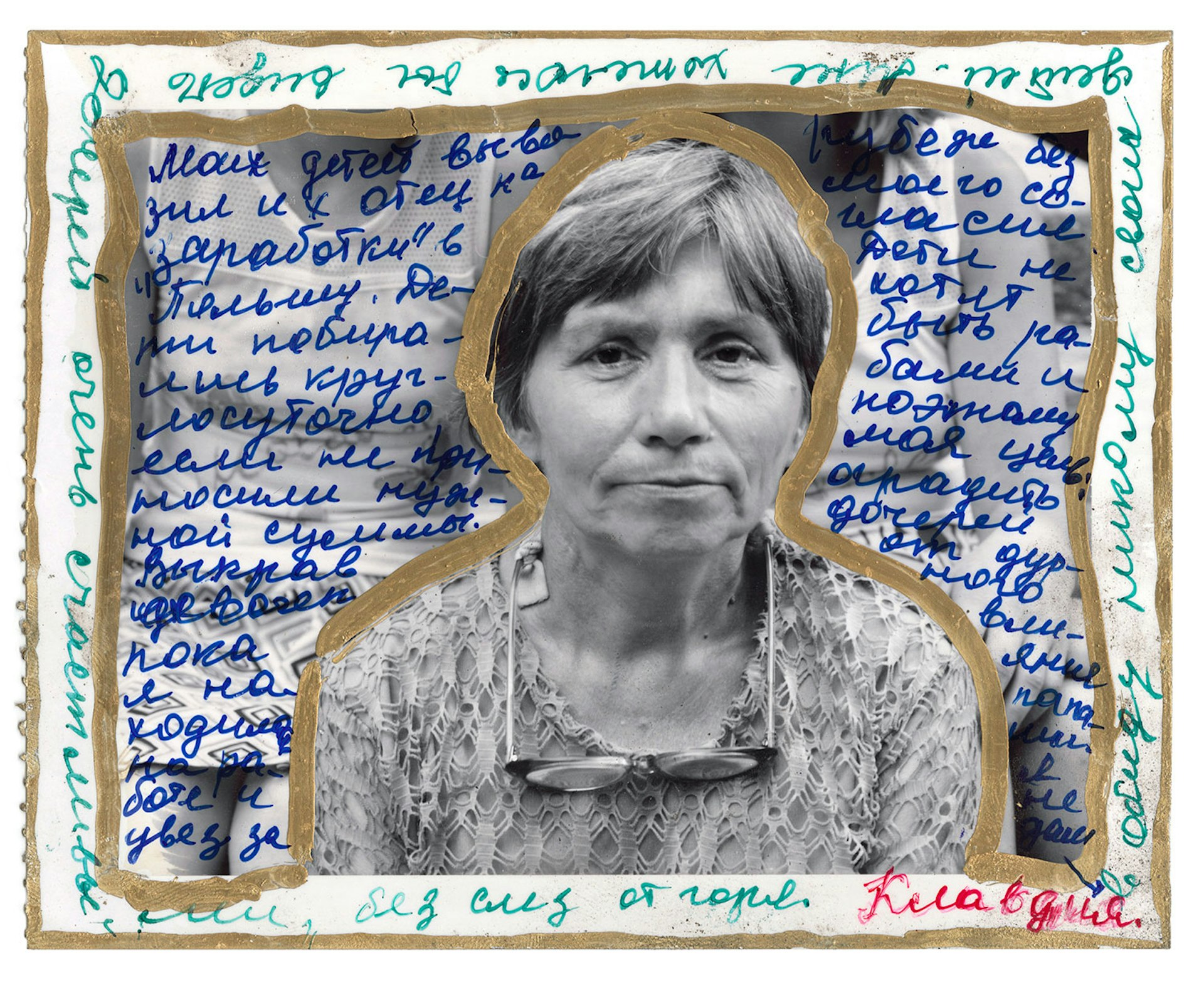

“I had the idea of having people write their stories on the photographs and, although I didn’t really know what I was doing, that turned out to be something really integral to my practice for 40 years. I just saw something that I felt I needed to try and make sense of. And using text enabled me to do that.

“At the time, a lot of documentary and photojournalism was from the outside looking in. And I was interested in something else – letting people describe experiences in their own words, from the inside, with pictures that sometimes supported, and sometimes perhaps undercut, what they were saying.

“I wanted to open up the picture, open up the discussion, to more complicated and sometimes contradictory discussions than economics or photojournalism would allow.

“Of course, once the camera’s trained on someone, they’re going to perhaps act for the camera, and if they’re writing words that they know are going to be there for a long time, they might also change what they say.

“But my role was as a guide; to help them elucidate what they were trying to say as accurately as possible to what they were thinking. People are amazing beings and when they speak from the heart, or intuitively address issues that are important to them, they’re very wise and clear about what they’re thinking.

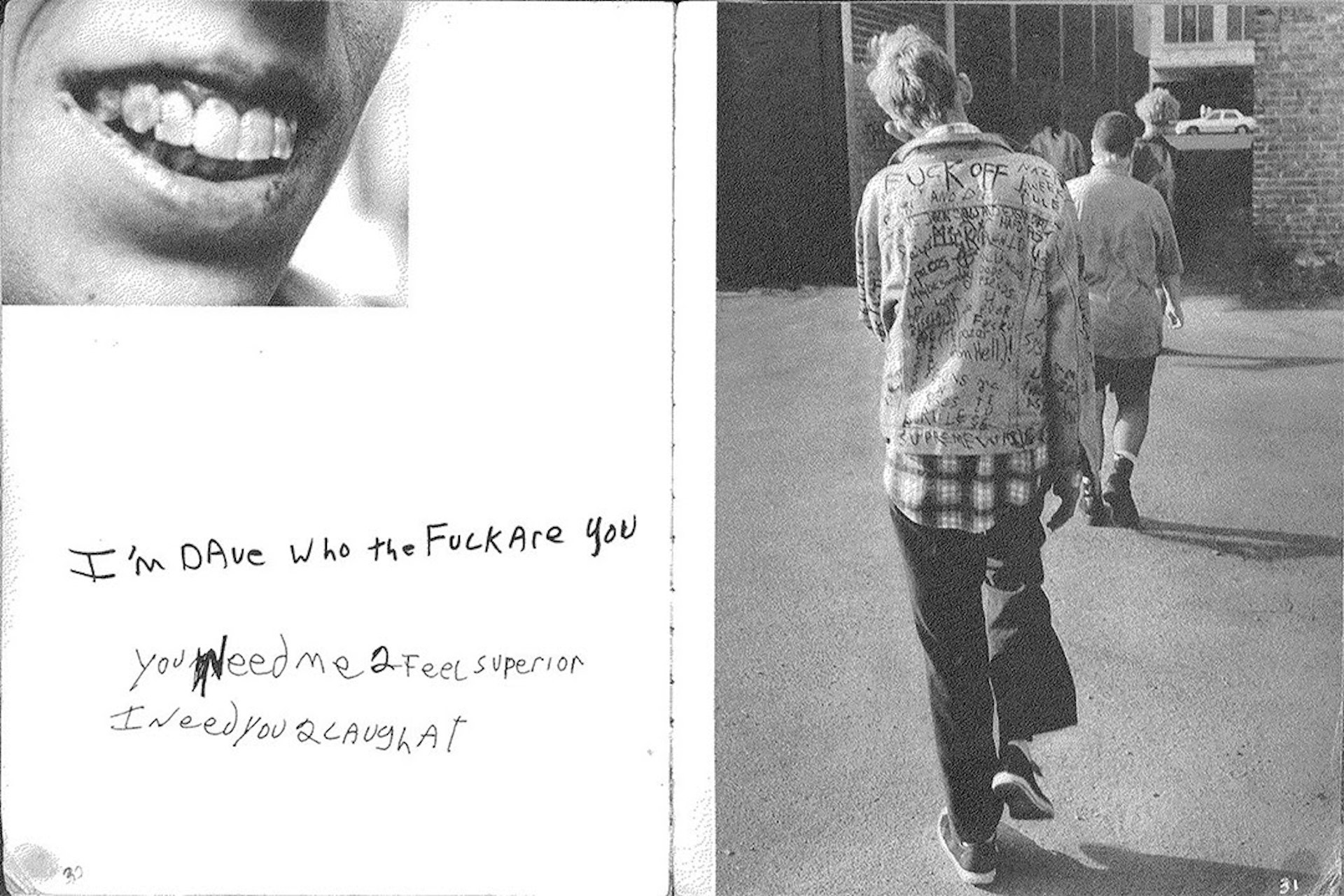

“I’m lucky in that I’m not a photojournalist and most photojournalists only have X amount of time in a place. Rich and Poor or Raised By Wolves or Open See; those were six to eight to 10 year projects. So of course that affords a level of intimacy and friendship that many people who are only working for a day don’t have. I feel privileged in that sense.

“My book Raised by Wolves talks about those relationships and how those people came into my life, stayed in my house, ate my food etc. Of course that’s difficult when you’re dealing with homeless youth and someone calls you at 3am in the morning, desperate because someone stole all their stuff, or it’s raining hard and they have no place to stay.

“But I think when you develop relationships, responsibility comes naturally. When I did Open See, I was photographing trafficked people, refugees and immigrants who were on the edge of Europe and didn’t know where they’d be the next day.

“Do I have a responsibility? I couldn’t save them. I couldn’t give them amnesty. I couldn’t give them citizenship. But yes, I have a responsibility in the moment to treat them with respect.

“If they wanted to collaborate with me to tell their stories – because they maybe thought it would help someone else, or the authorities even, understand what was going on – then yeah, I feel that responsibility.

“I’ve been using collaboration, or some people call it social practice, since forever. One of my newest works is in New Haven, where I was born, and I’m mapping the city by riding on top of an RV, photographing as I go through the streets. I’m mapping in a Google kind of way, but more Goldbergian, waving at people, telling them I’m photographing them. So even that in a sense is collaborative… I want to show people what a place looks like, with the participation of people who live there.

“I think we all hope that what we do affects a little change. I do these projects because I’m interested in making art and pushing mediums and playing and learning. It’s selfish. It makes me vital. It keeps me young to continue to work. Does it change things?

“I’ve read things and been told about things whereby my work has invoked change – it’s small stuff but small stuff adds up. Of course I hope that things change and get better, but whether my work, or anybody else’s work, does that or not, I don’t know. I’m just making work and hoping that some people look at it and like it and maybe do something with it.

“I can’t say I know what legacy I want to leave yet because I’m not done. There are so many more things that I need to do. Many people my age are retiring now. I can’t even imagine that.”

To pre-order Raised by Wolves, a new bootleg re-issue of Jim Goldberg’s seminal work, visit his online studio.

This story originally appeared in Huck 52 – The Documentary Photography Special III. Buy it in our shop or subscribe so you don’t miss another issue.