Inside life on Tijuana’s garbage dumps

- Text by Isaac Muk

- Photography by Jack Lueders-Booth

In May 1991, Jack Lueders-Booth travelled from his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Tijuana, just south of the USA-Mexico border. He had been in touch with Luis Alberto Urrea – a now famed writer and Pulitzer Prize finalist born in the city, who was working for the San Diego Reader at the time. Urrea had been in his home town, working on a story about landfill dumps that were lived in by hundreds of families, and invited the photographer to come with him to make pictures for it.

Upon entering the dumps for the first time, Lueders-Booth was horrified. Mountains of trash filled the skies as huge machines dropped and churned discarded items, food and dirt into the air. Among it all, people were picking through the trash, looking for anything that they could eat, sell, or take back to their makeshift homes to keep for themselves. Covering his mouth as stink filled his nostrils, he saw young men, elderly women in rags, and children wearing mismatched shoes picking through the piles of litter. Lueders-Booth turned to Urrea and yelled: “No, I am not going to photograph here.”

“It’s alright Jack – they know us,” Urrea replied. “Get your camera off your chest gringo.”

“So I did,” recalls Lueders-Booth of that moment, over three decades ago. “I raised my camera to my face, and that’s how it began.” He would return each summer for the next nine years, growing close to the community who lived there and making pictures of them. That work was first presented in his 2005 photobook Inherit the Land, and now those shots have been dug out of the archives for a new show at Gallery Kayafas in Boston.

The project provides insight into the incredibly tough conditions faced by those living in the dumps, among the machines and landfill. Many people died young, while diarrhea and dehydration were common. It came to highlight the chasm between the haves in the global north and the have nots between the global south, separated by a border fence of no more than a few metres high, spanning the divide between San Diego and Tijuana. “Perhaps two-thirds of the families were born into [the dumps],” Lueders-Booth explains. “The remaining are people from South America who have been moving up from Nicaragua, Colombia [and elsewhere] to get into the USA, and the final hurdle is the Tijuana border.”

Trash was often imported from north of the border, and scarce conditions fostered a hierarchy, where those who had been there for generations secured the best locations. “Much of the trash is from San Diego, and I don’t know what arrangement the city has with Tijuana that they dump their trash there, but it’s premium stuff because Californians own valuable things,” he says. “The people closest to the trash as it is coming in on the trucks have prime position because they get to see the trash first, and they have achieved the status by being there for a very long time. But this is quite touching – there are prime areas of the dump reserved for the elderly and infirm.”

In the face of common hardship, people still found ways to look out for each other. And that resilient spirit and humanity persists throughout the photographs. Kids can be seen playing in decommissioned cars, while Lueders-Booth also makes warm portraits of people in their homes, living ordinary lives and attempting to make the best of their situations. “[The resilience] was one of the most impressive aspects – how these people could not only survive these circumstances but rise above them,” he says. “I feel deeply respectful of those who are there and able to make sense out of something that we would never understand, and how mutually supportive they are.”

Inherit the Land by Jack Lueders-Booth is on view at Gallery Kayafas in Boston until February 10. For more information about purchasing the photobook, visit his website.

Follow Isaac on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Meet the Kumeyaay, the indigenous peoples split by the US-Mexico border wall

A growing divide — In northwestern Mexico and parts of Arizona and California, the communities have faced isolation and economic struggles as physical barriers have risen in their ancestral lands. Now, elders are fighting to preserve their language and culture.

Written by: Alicia Fàbregas

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

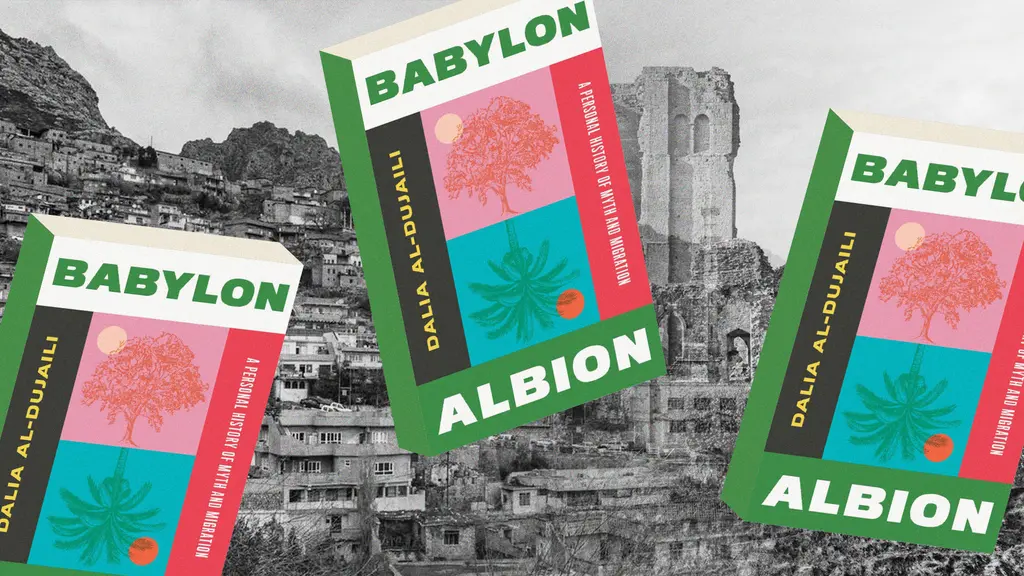

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro