Capturing the everyday reality of lockdown in Soweto

- Text by Eva Clifford

- Photography by Jabulani Dhlamini

In a televised address on March 23, the President of South Africa – Cyril Ramaphosa – announced the start of a 21-day lockdown on the nation’s 59 million inhabitants to curb the spread of coronavirus.

Liquor and tobacco sales were banned, non-essential outings prohibited, a curfew was enforced and face masks became mandatory. Meanwhile, the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) was deployed, ensuring that people obeyed the government measures and dishing out heavy penalties to those who didn’t.

Within the first week of the lockdown, three million South Africans had lost their jobs, contributing to a sharp rise in food insecurity and poverty. But one of the hardest-hit areas was Soweto, a sprawling township on the outskirts of Johannesburg, home to more than a million people – the majority Black Africans.

It’s in Soweto that photographer Jabulani Dhlamini lives and works. “As a documentary photographer I am compelled to look, observe and document what is happening around me,” he tells me. “My practice is always about looking at human conditions and how the past is affecting the future… so I felt it was important that I document this part of human history.”

“The first funeral ekasi lami ePhiri after the lockdown was announced. It was not easy because the regulations were just announced, so we had to turn back other people. Other family members couldn’t come to attend the funeral which is unusual in our culture.” Ha Matsheka

During the lockdown, Dhlamini was driving his mother – an essential worker – to and from the pharmacy where she works. As the streets were largely empty, he’d find himself talking to people out the car window while he waited. Each conversation inevitably wound back to Covid-19, as people shared their fears and frustrations with him from the doorways of their homes. So it was that Dhlamini’s new project, the everyday waiting, was born, as a means to archive and visualise these conversations.

Soweto was once the epicentre of the famous 1976 uprising that bears its name against the racist apartheid regime. What began as a peaceful protest, was quickly succeeded by years of violence and repression. Today, conditions have not changed much. Families live crammed into informal shack settlements or single-room houses, which make social distancing during a pandemic near impossible. Many in Soweto lack access to basic facilities, including running water and electricity.

“Covid-19 has exposed South African social problems that are a legacy of the apartheid system,” says Dhlamini. “Not a lot has changed even after 25 years. For example, people still live in the same houses that were designed during the apartheid era under the Group Areas Act.

“Financial exclusion is making townships overpopulated, as people can’t afford to own houses in cities. So now, people are forced to live in hand-to-mouth situations as they earn way less than their counterparts from other races.”

“At least afukani, I am able to be selling umbila la now, a few weeks ago I had nothing to eat at home. I always have my mask on and sanitiser to protect myself. Otherwise, if I don’t come here to sell I won’t have money to buy food.” Alis Maphosa

Police brutality is also rife. While nothing new, the rate of violent incidents by police against civilians has reportedly more than doubled since the lockdown began. According to the Thomas Reuters Foundation, at least ten Black people were killed by police during lockdown in South Africa.

Dhlamini had his camera seized by police at one point while shooting the project. “All the townships were militarised and over-policed and that resulted in police brutality,” he says. “I had an encounter with the police and they made me delete images; that experience meant I had to tread carefully going forward.”

While Dhlamini photographed people from his car, there is a striking intimacy to his portraits, reflective of his sensitive approach towards the people he photographs. The conversations were the genesis of the project, therefore he’s chosen to present their quotes alongside the pictures.

“The corona thing does not sit well with me, I am praying that it ends, I hope we can work together as a community, stay home and always wear a mask please! Maybe izophela lento. I can’t stand the trauma of staying at home and not knowing where our next meal will come from. Lockdown level 5 tortured me because I live a hand to mouth situation, this is my only source of income.”

“In this process of me collaborating with the people I’m working with, photographs become my contribution and the text is their contribution, so I have to tell their stories in their own way,” says the photographer.

It is estimated that around one in 10 of Johannesburg’s cases of COVID-19 are in Soweto, following a trend seen in Cape Town, where the poorest townships have been most affected. These inequalities – still glaringly present decades since the apartheid era – are what Dhalmini seeks to highlight in his work.

Like his late mentor David Goldblatt, who famously documented Soweto during apartheid, Dhlamini regards photography is a tool he hopes will bring visibility to social issues and ultimately trigger change.

“Shooting my surroundings at this time led me to understand that this pandemic is starkly highlighting entrenched social and economic problems,” he reflects. “After 25 years, what has changed in South Africa’s townships and rural areas? Not enough.”

“I recently lost a job due to the COVID 19, so just getting food for a day is very difficult especially under lockdown. I just hope our government could be honest about food parcels.” Gertrude Phiri with her daughter (Rebecca Phiri), and her grandchildren.

“I am from Lesotho and work in construction here in South Africa, so now life is very hard because we have already used our savings and I can’t go back home.” Thabang Seboka

“I worked as a domestic worker before the lockdown and I had to stop due to COVID-19 and I don’t know if I will get my job back after this. I have not been getting anything from my bosses because no work no pay, you know.” Lebohang Raethole, Boitumelo Mathibu and her kids

View the online presentation of Jabulani Dhlamini’s the everyday waiting on The Goodman Gallery website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

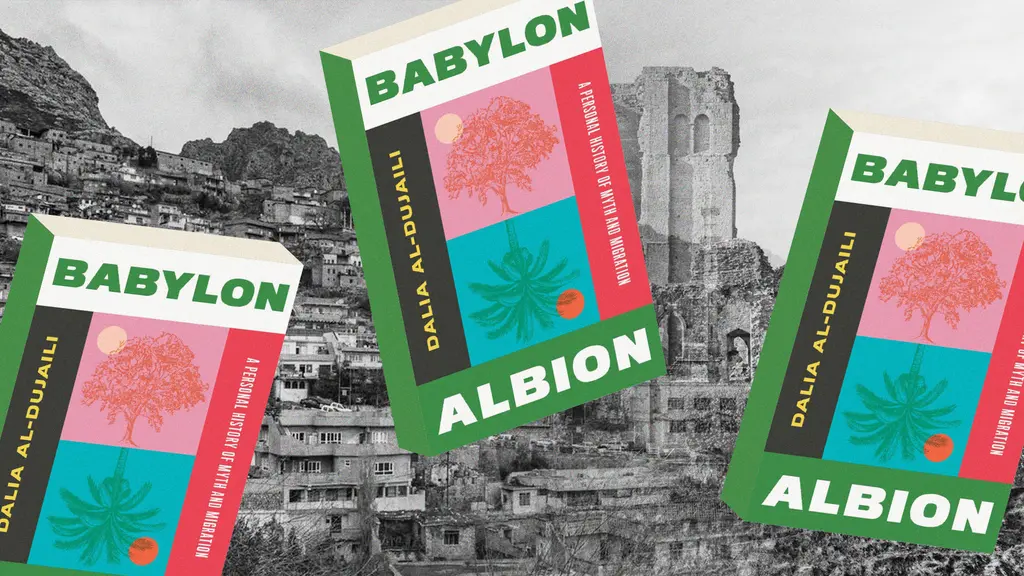

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro