To Hell And Back: Sixty-nine days trapped 700 meters down a Chilean mine

- Text by Adam Patterson as told to Andrea Kurland

- Photography by Adam Patterson // Panos Pictures

In 2010, Andy Bell – a producer from Panorama at the BBC – called me up and said, ‘Have you been following the news? Thirty-three Chilean miners are trapped underground – and they’re still alive!’ We’d worked together previously on a story in Dubai on slave labour. Panorama wanted to make a film around the rescue effort, and Andy invited me to join a small team – a fixer and assistant producer Alexander Houghton – to meet with the families and find stories before he and reporter Dan McDougall joined us.

“When we arrived the rescue effort was gaining pace; the four of us ended up shooting the film over a frantic six-week period. Most press were focused on the rescue as a technical feat, but we wanted to focus on the miner’s families. They didn’t know if they would ever get their loved ones back.

“Eventually we met Angelica, whose boyfriend, Edison Pena, was underground. There was this contraption called a paloma – the word for dove – that lowered things down to the miners. Angelica would send love letters to Edison, and the government started sending cameras and releasing imagery to show these guys were alive.

“The footage was obviously PR managed, but it got us thinking: if we could get a camera down there and have someone shoot with an open agenda – not controlled by the Chilean government – then we’d have an honest depiction of what was happening. But we couldn’t ask someone to send it down in case they had their rights cut off. The families received one TV link a week, for something like three minutes. Losing that would destroy them.

“One day Angelica was explaining to us how upsetting it was to only see Edison on the state-controlled video links; she wished she could see how he really was. Cautiously, we mentioned our idea, and she loved it. Edison was known as ‘The Runner’ – he was running underground as a way of keeping sane – and she wanted to send him running shoes. So we bought a really small camera, put it in the shoes, and Angelica wrote a letter that said, ‘Take this and show us what it’s really like.’

“Three days passed and no word. Then Edison and Angelica had this big fight – understandably, he was becoming unhinged – and she stopped coming to the mine. We wrote off the idea. Then on the day before the rescue, the miners were instructed to send up anything of value. Later, Angelica called to say, ‘I’ve got the memory card.’ Getting to her without anyone knowing became an undercover mission. We were surrounded by 2,000 media jackals desperate for news. Whatever was on that card was the only footage not controlled by the Chilean government, and if they got a whiff of this they’d tear us apart.

“So we met Angelica in the back of a van. We put the memory card into the reader and a list of images popped up. Our hearts were pounding. The first images were black. Two, three, four, five, six images – just blackness. Then boom! This picture of Edison’s face came up, like a selfie. There were pictures of him posing around huge rocks, and then a series of him running, lifting iron bars. It was so surreal, it was unbelievable. Here were pictures of a man trying to fight off his demons and maintain some kind of sanity while wrestling with the notion that there’s a very good chance he may never see daylight again.

“It shifted our understanding of the person we thought we knew. We thought we knew this guy because we’d read his letters, then we saw images of a person going through a struggle that was more intense than we could have ever imagined, occupying his mind through gruelling exercise. Here was a visual document that will stand alone beside his story, and a photographer could not have done that.

“I learned a lot from that. I learned that there are different ways of telling stories. When you’re young, you assume that the story is only yours if you take every picture. But it taught me that that’s not always the case. I formed a situation whereby the pictures were taken, so part of that experience is mine. As a younger photographer you focus so much on getting amazing imagery that you think less about how it impacts people. People can be so willing to do things for you, they may not realise how that will affect them. Working with the BBC I had to become more practiced in ethical responsibility.

“Chile became a turning point in my career. I went there as a researcher and stills photographer, and walked away with experience in film. It also taught me the importance of collaboration. There’s a school of thought that young photographers often grow into; I certainly did. You convince yourself that all you need is one great idea that nobody knows about, and you’ll somehow be propelled to a higher level. But it’s a very dark and lonely path; you spend a lot of time ignoring other people, so when it doesn’t work out your whole world falls apart because you’ve got no one else to turn to.

“But you don’t have to do it all alone. You can talk to people. They’re not going to steal your ideas and even if they do they’ll do it in a different way. Don’t compound pressure on yourself to do something completely unique. Talk to other people, see if they’ve got ideas that align with yours, and even if you don’t work together they may shape your thinking in a way that brings you to a much better place.”

This story originally appeared in Huck 52 – The Documentary Photography Special III: Collective Truths. Buy it in the Huck Shop now or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

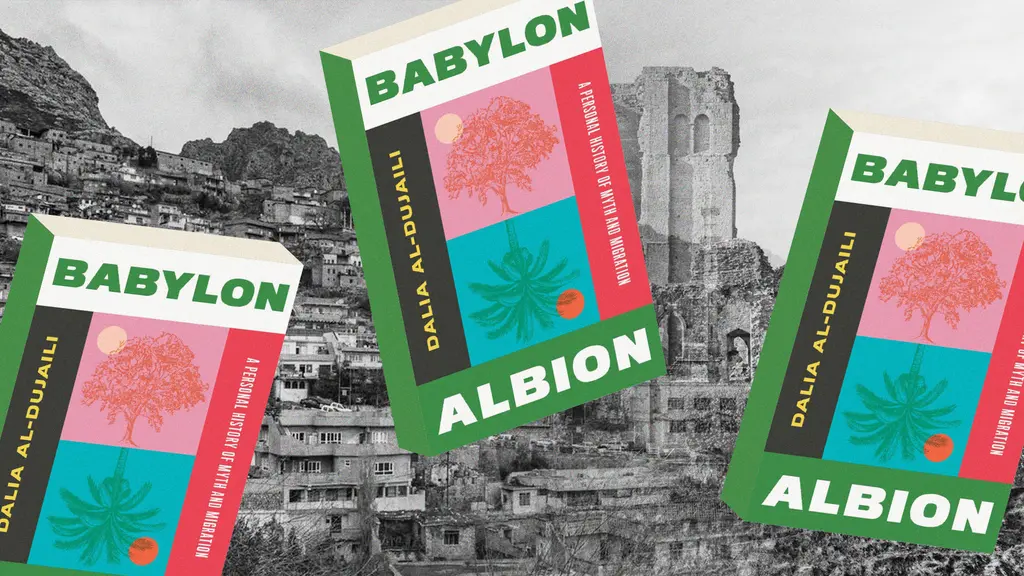

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Southbank Centre reveals new series dedicated to East and Southeast Asian arts

ESEA Encounters — Taking place between 17-20 July, there will be a live concert from YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, as well as discussions around Asian literature, stage productions, and a pop-up Japanese Yokimono summer market.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro